AI financing boom begins to show cracks as investors balk at debt binge

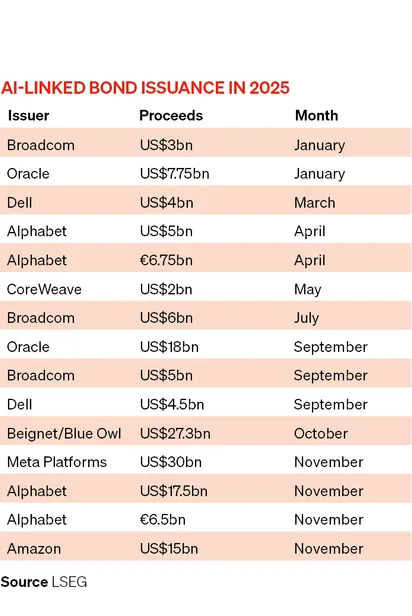

The AI financing boom may only just be getting started but cracks are already beginning to appear as investors struggle to digest US$120bn of bonds sold by technology firms over the last eight weeks, raising questions about their willingness to fund the enormous sums that are still needed.

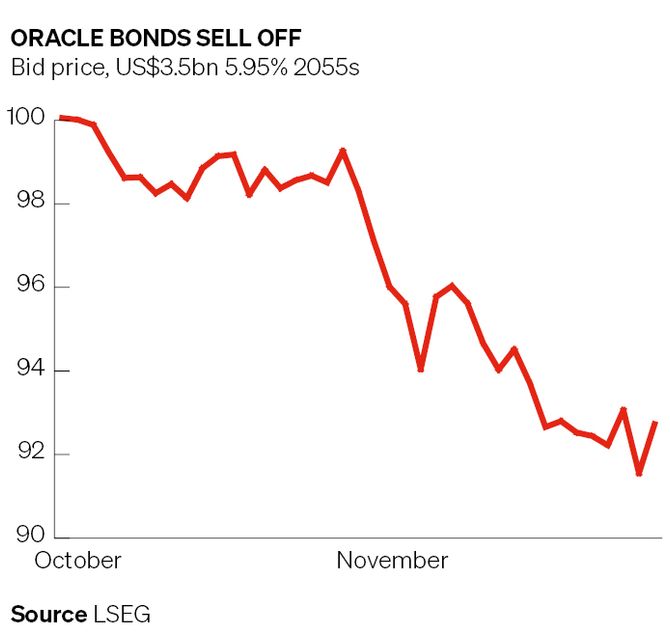

Oracle has been at the centre of the storm, with the US$18bn of bonds it issued amid much fanfare at the end of September selling off significantly. Its 2055 and 2065 bonds have fallen by about seven points each and investors are sitting on US$750m of paper losses on the total deal.

While bonds issued by other hyperscalers have held up well, signs are emerging in the credit default swap market that investors are starting to become uneasy with the volume of debt they are taking on, with the cost of insuring against a default in Meta Platforms' debt almost doubling over recent weeks.

“We've definitely seen some softness in the AI hyperscalers,” said Meghan Robson, head of US credit strategy at BNP Paribas, who said the bank had become “more cautious” about the amount of debt expected to come. “More supply will continue to weigh on spreads.

“People are starting to think more and more about the huge supply coming down the line,” she said. “I think there are also some wider questions: some of these deals include 30 and 40-year bonds, but what will these investments actually result in? Many are a long way from generating free cashflow.”

Shrugged off

For now, bankers are shrugging off the selloff and ploughing ahead with plans to return to the markets with a flood of hyperscaler issuance in January. While the recent price action has caught their attention, there is widespread confidence that the deals will get away – albeit at a higher price.

“You’ve got to remember that these big debt deals that are coming are from some of the world's biggest companies that are all incredibly rich – both balance sheet-wise and top line-wise,” said a banker involved in two of the recent hyperscaler deals.

“It’s a lot of money – but they'll be absolutely fine,” he said. “These companies are starting from a base of extraordinary strength. They can afford to make these big investments and be leaders in the industry – a lot of other companies simply don’t have that ability.”

January is expected to be a busy month, with hyperscalers set to frontload a lot of the bond issuance planned for next year. After US$160bn of deals this year – mostly in the past two months – JP Morgan is expecting US$300bn of AI-linked bond issuance next year and US$1.5trn by the end of 2030.

How the market digests those deals in January will be critical – not least because bond markets are considered to be the only funding source large enough and deep enough to raise the trillions of dollars hyperscalers plan to spend on data centres, energy infrastructure and cutting-edge chips.

“The numbers are just too big,” said one technology banker at a US firm. “The bank market just isn’t deep enough – we can’t provide a US$30bn loan facility. When you have these extraordinary investment programmes, the capital markets are going to be the only way to finance that.”

Support

The technicals should be supportive, with lots of cash coming to investors that will need to be put to work. Some US$1trn of bonds issued during the enormous bond deluge at the start of Covid-19 will mature next year, while coupon payments will reach a record US$500bn.

Nonetheless, some are beginning to worry about the pace of debt accumulation. Alphabet has almost tripled its borrowing in less than a year, with gross debt now US$57bn. If its Hyperion debt obligations are included, Meta has done almost the same. Its debt is now close to US$86bn.

And this is just the start. Predictions vary, but analysts expect hyperscalers to spend at least US$500bn a year on developing AI between now and 2030. The hundreds of billions they generate in free cashflow will pay for some of that, but about half is expected to be financed in bond markets.

While bond markets might appear calm for the big names, analysts say that is a reflection of the relatively illiquid corporate bond market. The real action, they say, is taking place in CDS markets – where trading has soared as some investors buy protection against the the potential of hyperscalers getting into trouble, or at least damaging their credit standing, from those (presumably) who think all will be well in the new AI world.

“The cash price tends to be more sensitive to technicals and supply, whereas the CDS is more liquid – and so in theory a better reflection of the fundamentals and the credit risk,” said Robson. “In the cash market, price is affected by imbalances between supply and demand.”

Oracle seems to be the favourite name to bet against. Its five-year CDS hit a high of 124bp in recent days, having nearly tripled since September. The cost of buying 10-year protection reached 170bp, the highest since records going back to the global financial crisis, implying a one-in-four chance of default.

The big names are not immune: Meta has seen its five-year CDS rise by about a third since the beginning of November to 58bp. The 10-year contract reached 78bp, almost double its level just a couple of weeks ago. While such levels imply less than a 5% chance of default, the shift in sentiment is significant.

Irresponsible

Gil Luria, head of technology research at boutique investment bank DA Davidson, said the current dynamics playing out in the market are concerning. His firm put out a note recently warning that Oracle may have borrowed “too much” for revenue that “may not materialise”.

“We get into trouble when we use debt to finance things that are supposed to be financed with equity,” he told IFR. “We especially get into trouble when we use debt financing for speculative investments. And we get into even more trouble when we use that debt to finance the acquisition of assets whose lifecycle and whose economic lifecycle we don't know anything about.”

He expects the financing wave to continue – but warned about potential trouble brewing.

“As far as Meta is concerned, this is great,” he said. “If the capital markets are being irresponsible and all this debt is being underwritten when it shouldn't be – at very low rates, which it shouldn't be – why wouldn't I take advantage of that? I don't have to deal with the repercussions.

“But CDS investors are saying: 'this is so risky, there's at least a ... chance these companies go bankrupt in the next five years',” he said. “We're not pricing in a likelihood that they go bankrupt. That's telling you that the market has already gone awry. And it's trying to do more.”