Strategy: when ‘general corporate purposes’ means keeping the lights on

Most prospectuses contain a line so familiar that eyes slide straight past it: “We intend to use the net proceeds for general corporate purposes.” It sounds comfortably dull.

But it does a lot of heavy lifting.

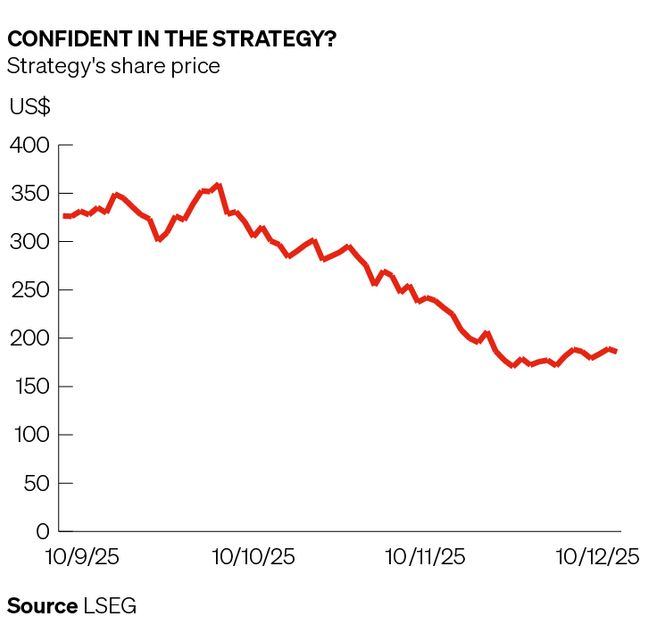

That is especially true when it comes to Strategy, a company (formerly known as MicroStrategy) that describes itself as the “largest bitcoin treasury company”.

For all securities issued under Strategy’s shelf registration, the base prospectus supplement (at section S-12) states: “We intend to use the net proceeds . . . [for] general corporate purposes, including the acquisition of bitcoin and for working capital, and the payment of cash dividends.”

In theory, “general corporate purposes” is a catch-all for the things a normal company needs to stay alive and, ideally, make money. Working capital. Operating expenses. Capex. Maybe a bit of M&A. It is deliberately broad because issuers want flexibility.

If you pin proceeds to a specific project, you invite follow-up questions on progress. “General corporate purposes” is, in part, disclosure that cannot easily be proved wrong. Strategy’s base prospectus supplement makes this clear. “Management will have broad discretion in the application of the net proceeds from these offerings,” it says.

The expression also sounds reassuringly close to “corporate operations”, which investors instinctively hear as “things that generate corporate revenue”.

That logic holds for a bank that lends money for a return, or an industrial company with factories that make stuff. But the more a company starts to look like an investment vehicle rather than an operating business, the weaker that link becomes.

An uncomfortable pattern

Strategy’s core activity is straightforward: it holds a large position in bitcoin, funded through a mixture of common equity, debt-like instruments and preferred stock.

The preferreds create a fixed or quasi-fixed cash obligation. The underlying “business” does not generate sufficient recurring cash to cover that obligation. The gap has to be filled somehow.

There are only three real sources of cash to pay the preferred dividends: bitcoin sales, operating income or fresh capital. If operating income is thin and the strategic intent is to increase bitcoin exposure rather than run it down – year on year since 2020, Strategy has only increased its bitcoin exposure – then the burden shifts to capital markets.

Strategy, to its credit, states in its STRC preferred stock prospectus supplement (S-11) that it expects to fund cash dividends “primarily through additional capital raising activities”, including at-the-market issuance of common and junior preferred stock.

There is nothing impermissible about that. Corporate law does not insist that new equity be raised only to build factories and fund capex. Companies routinely raise equity to plug losses, repair capital, meet regulatory requirements or refinance other instruments further up or down the structure. Using equity proceeds to meet obligations associated with other equity can sit comfortably inside “general corporate purposes”.

But in Strategy’s case, this all looks . . . circular. Fresh capital is used less to build cash-generating assets than to support preexisting capital. Push that far enough and most of what holders receive is funded by new investors rather than by operations or assets. At that point, the economics start to look uncomfortably close to a Ponzi-like pattern, even though nobody is committing fraud.

A simple litmus test

Assume capital markets are closed for 24 months. No equity issuance, no opportunistic converts, no quick taps. Can the issuer meet the cash obligations on its preferred and other quasi-fixed claims from operating income and a sustainable level of asset sales? Or does the structure depend, implicitly, on continued access to markets to roll and service itself?

If the answer is the latter, “general corporate purposes” is no longer about normal operations. The proceeds are integral to keeping the whole structure upright. Capital issuance decisions (whether preferreds, converts or common), are made primarily to support the core investment stance of staying long bitcoin.

The credibility of that stance in turn relies on the assumption that the company can always raise more capital. It becomes a circular arrangement in which capital raising keeps the investment thesis alive, and the thesis only works as long as capital raising remains possible. The corporate purpose becomes keeping the investment thesis alive, rather than testing whether it still holds. At that point, the crucial asset is no longer the business, but the market’s willingness to keep providing cash.

Of course, Strategy could always switch off dividend payments on its non-mandatory preferreds, but in doing so it might kill the very asset that’s keeping it alive.

All this explains why Strategy has established a US dollar reserve of US$1.44bn, funded from common stock sales, specifically to support the payment of dividends on its preferred stock and interest on its debt. Strategy’s stated intention is to maintain a reserve sufficient to fund at least 12–24 months of these payments.

None of this makes an issuer like Strategy inherently illegitimate. Investors may be perfectly happy to buy into a leveraged exposure to bitcoin, knowing full well that their dividends will be paid from a mixture of asset sales and future capital raises. But they should at least be invited to see it clearly. The boilerplate use-of-proceeds paragraph does not help them do that.

Mind the gap

“General corporate purposes” will remain in documents. It is too convenient and too well established to disappear. But in the environment we are in, it should no longer be allowed to pass unexamined. The line may be generic, but investors cannot afford to read it that way.

Investors should at least be asking: what is the source of cash here? Does this security fund a business, or does it mainly fund other securities? If new capital dried up, would I still be paid? These are not radical questions.

Strategy has gone further than many by admitting that cash dividends on its preferred shares are expected to be funded primarily through additional capital raising. What it does not do is quantify how dependent the structure is on that assumption. That is the gap that “general corporate purposes” still leaves open.

Prasad Gollakota is a former FIG banker and co-head of the global capital solutions group at UBS. He was later chief content and operating officer at edtech company xUnlocked and specialises in financial institutions, banking regulation, capital markets and complex capital and funding solutions.