An expanding Asia needs ever-greater resources to fuel its growing economies. Balancing growth with sustainable development, however, remains a challenge.

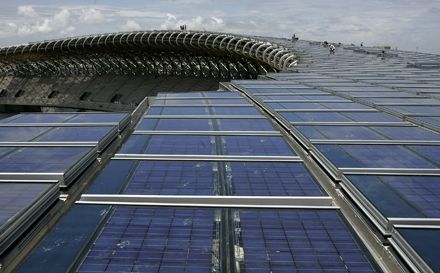

Source: Reuters/Pichi Chuang

People work on the roof of the main stadium of the World Games 2009, which is made of solar panels, in Kaohsiung

last month were quietly putting the finishing touches to a gleaming array of solar panels on the roof of the ADB’s Manila headquarters. Aside from meeting some of the bank’s electricity needs – not to mention improving the aesthetics of an otherwise drab, flat-roofed compound – the project is designed to illustrate that green energy projects can be feasible in an urban environment.

It may be more of a trophy project than a commercial venture, but the ADB’s 5,000-square-metre solar roof is an appropriate symbol for the region. No longer facing the threat of a global financial crisis, but with the poverty line still high, Asia needs to explore new, sustainable technologies as it embarks on its next phase of growth.

“As populations continue to rise and energy consumption increases, Asia will have to look at this issue very seriously,” said Bindu Lohani, ADB vice-president for knowledge management and sustainable development. “It is in Asia’s own interest, in terms of energy security, that countries move towards clean energy.”

There are signs that governments in Asia are taking the initiative seriously. It is no coincidence that the two countries with the biggest energy needs –- China and India –are among the world’s biggest investors in solar and wind power.

Cost remains a major hurdle. Solar energy is expensive, and the ADB is finding its services in hot demand from project sponsors looking to reduce their overall financing costs. To that end, it is providing partial credit guarantees of up to US$150m to support small solar projects in India ranging from 2MW to 25MW.

It is also bankrolling US$240m to China Wind Power Group for the construction of a series of wind farms in Jilin and other provinces in northern China, targeting supply of 800MW come 2013.

There are plenty of other reasons, too. Bangkok, Manila, Jakarta and other Asian mega-cities are susceptible to severe flooding and, as climate change advances, their problems are likely to get worse.

“This region is vulnerable. We believe in the science put up by the IPCC. If that is a correct prediction, many countries in Asia are very vulnerable in terms of their economic growth and flooding due to a rise in sea levels. It is in the economic interests of these countries themselves to address such issues,” Lohani said.

Thailand’s floods in 2011 underlined the need for climate-resilient investment. The country’s GDP growth for the year came in at less than 1% versus estimates of over 4%, with an estimated US$45bn of direct economic damage before even taking into account the impact on global supply chains.

“The Bangkok floods were a huge wake-up call for the region,” said Stephen Groff, vice president (operations 2) at ADB. “The Thais realise that their economy, their government and their international reputation really hinges on their ability to address successfully the issue of future floods.”

Asia’s responsibility

Global manufacturers will have seen the images of muddy water running over thousands of submerged cars outside Thai factories, and will think twice before centralising their operations on a low-lying flood plain in Asia. Countries will need to learn how to adapt their existing infrastructure to make it climate resilient – again at additional costs.

Asian governments may be taking the environment seriously, but paying for expensive new power technology or sea defences is another matter.

Concessionary money is available, to some degree. The US$6.5bn Climate Investment Fund is about to be surpassed by a Green Climate Fund that promises US$30bn–$100bn a year for United Nations-promoted environmental projects and, potentially, operating in partnership with multilateral development institutions, such as the ADB. Progress, towards that goal, however, appears to be slow.

Asia needs to develop its own sources of funding, too, including attracting private-sector support wherever possible.

To that end, discussions are running behind the scenes on a climate public-private partnership fund (CP3), in an effort to leverage a small amount of public money with greater private sector investment. CP3 will work as a fund of funds, investing in multiple projects and managed by a private sector general partner. The ADB would not comment on its commitment, but the UK’s Department for International Development has already announced its participation. Commitments under discussion are around US$100m each from the ADB and the UK, with a target of a total capital of US$1bn. Credit Suisse has been linked with the general partner role.

On a smaller scale, in 2011, the ADB injected US$40m into two venture capital funds, primarily engaged in markets in China and India, which will invest in early-stage low-carbon technologies that address climate-change mitigation and adaptation, as well as environmental protection. This initiative is expected to leverage over US$400m in private-sector investment.

Leveraging private-sector involvement will be the key to the success of these funds. The UK has pledged that CP3 will mobilise £30 (US$48) for every £1 of government money. That may sound like a tall order, but it is clear that private-sector investors are interested in climate-related opportunities.

The ADB’s own clean-energy bonds, at tenors of four to seven years, have raised US$244m and broadened the bank’s investor base since they were first launched in September 2010 to retail and institutional investors in Japan. The majority of the more than 20 securities houses involved were first-time distributors of ADB paper.

Just as the ADB is sending a signal with the solar panels on its own roof, Lohani believes Asia now has an opportunity to look again at how projects are selected and make moves towards becoming a low-carbon society.

“The global target of a temperature increase of two degrees by 2050 is impossible to meet without everyone participating. The old arguments, that the developed world should pay and that the developing countries had nothing to do with it, are increasingly becoming less relevant,” he said.