To view the digital version, please click here.

IFR: Can you expand on the point about this new class of investor comfortable with the new class of instruments. Who are these people and what does the instrument look like?

Oliver Sedgwick, Goldman Sachs: If you roll the clock back to 1999/2000, when Tier 1 started, it was a yield enhancement product and the private banks were the biggest buyer of it across Europe and Asia. That bid is still evident. It’s definitely stronger in Asia than it is in Europe hence why dollars have been the resort for the majority of issuers that have gone down some loss-absorbing or hybrid capital, perpetual capital route. There’s still a lot of capacity there. The question is how much, and when does it run out?

It’s a levered investor base that buys it and the cost of leverage is low, i.e. base rates are low. If rates go up then their returns, assuming a stable coupon, come down. If we look at where banks have printed Tier 1s, there haven’t been many that have printed north of 10 so that kind of becomes a self-policing level based on the ROE that you can make, or just the cost of running that capital.

It’s going to be a smaller issuer class, because not everyone can afford to run it. But for those that do, I guess it’s going to be the private banks. And then there are dedicated funds that are building. And there are the asset managers who are focused on this and rewriting mandates to encompass exactly those terms which are clearly less palatable.

But if you’re happy to do your risk and come up with some way to hedge the instruments, that’s probably more the difference. The difficulty in the genesis of the real money bid at the moment is hedging these. But then I guess that’s how you form a sustainable investor base. The more stable the environment, the deeper it will become, because there’s less requirement to actually hedge those instruments.

And on the Tier 1 side, what do they look like? I think for the best- in-class names, conversion to equity or permanent principal write-down at 5-1/8% at non-viability is saleable at the moment. And that’s probably the Dutch, maybe some of the UK issuers that are willing to pay the price. Maybe some of the French, if there’s some clarity in regards to peripheral exposures and the like. But it’s a small subset, going back to David’s point. It’s not a product for everyone at the moment.

Sandeep Agarwal, Credit Suisse: I agree with Olly that you will ultimately end up having people who understand the risk and therefore are happy to buy it. And if that means separating out or segregating the funds that can afford to take that risk on, it’s going to be the way we move forward.

But the reality that I see in the banking sector versus the corporate world is the point of non-viability in a bank is typically achieved much earlier before the equity is fundamentally written down to zero i.e. we ask our banks to become non-viable when we reach 4.5% for example. This means fundamentally there is going to be equity in play or existing shareholders in play.

The point about hierarchy is a very fair one. I think fair is the term I would use, more than wiping out the equity holders as the basis for thinking about how losses should be imposed i.e. the next provider of capital should get the proportionate amount of ownership of that entity, as opposed to assuming that we will need to wipe out the equity as the only basis for provision of capital.

On the issue of regulatory discretion, I fear that national regulators in this environment are not about to give up all their discretion. So I suspect we will have to live with that level of uncertainty. Whether we can price that risk or not is a question mark. What is that price? Whether that price is already reflected in today’s instruments is an argument one can start to make. When we talk about the low interest-rate environment we’re in currently, the rates at which these risks are being financed are fairly onerous already.

I take the point about RWA. There has been upward adjustment around RWAs as Basel III kicks in, but I don’t think it’s a clear and fair reflection. That’s a credit assessment job that we all have to do around the risk profile we’re really buying. My point being that the instruments that are being designed, not for yesterday but for the future, are assuming that the banking system is a little bit more stable than it was before.

The level of uncertainty, unfortunately, in this environment at least, as we sit here, is fundamentally going to be higher than it was before. And one just needs to deal with it, or ultimately go to a model where equity is the only basis for financing this risk or business model. I think fundamentally banks have to be a leveraged play; otherwise there is no business model. These debt instruments will find a place at some point in time, if not now.

David Marks, JP Morgan: I think there has been an important change in that regard. There’s definitely been an attitude amongst regulators and policymakers, which is frankly not to listen to our input or to take it onboard fully, on the assumption that we will build it and they will come, meaning the investors. However, we’ve seen painfully over the past couple of years that buyers strikes can and do occur and it can be comprehensive in terms of shelving entire asset categories like European government bonds from significant swathes of European countries.

I think there’s also an increasing recognition that the equity capital markets are also not going to be there to recapitalise the banks. We talked about how short the list is of banks that can access the markets. It’s a shorter list that can do a rights issue at this particular point in time.

So, given that we have, I think, fundamentally good quality, better quality capital instruments this time around, there’s a greater willingness to take them on board because it would be a tremendous missed opportunity, if after all these years of redeveloping the instruments we find something which is sellable, or relevant only to a very small sub-stratum of financial institutions.

IFR: How much capital needs to be raised in non-senior form?

David Marks, JP Morgan: We know what the components of capital are and we know that the banks will have 1.5% in Additional Tier 1 and 2% in Tier 2. It makes sense for them to utilise those buffers in full. And it would make sense for most banks to be running a buffer to that buffer, so perhaps a 2% AT1 and 2.5% Tier 2 ratio.

As Sandeep points out, in terms of the context of bail in, theoretically there is room for a number of banks to be able to make use of shorter dated sub debt, which is not necessarily regulatory capital qualifying but is there as a buffer for senior creditors.

IFR: You mean sub five year?

David Marks, JP Morgan: Sub five year, maybe three year sub debt which is explicitly providing a buffer to those further up the capital structure. And I think the challenge is …

Oliver Sedgwick, Goldman Sachs: … the refinancing agenda. We ran some numbers and it was about US$500bn of European bank capital outstanding; something like US$200bn in Tier 1 and the balance in Tier 2. And how much Lower Tier 2 does the average bank hold? It’s currently about 4%. So, going back to your question as to what the number is, it’s probably north of 2.5%, dependent on whether banks can realise a cost efficiency in running more Lower Tier 2 in a tighter senior funding spread. So, from that perspective, it’s probably an asset class that’s in decline and going to decline relative to what is actually needed.

Sandeep Agarwal, Credit Suisse: I’ve got a different take on the numbers. It won’t be purely refinancing led in my view because I think the capital structure needs to be decided first. I would think that the European banking sector has RWA of around US$15trn and the capital structure of the banks will be in the context of 15%-20% total capitalisation, of which 10% is likely to be in core format. That leaves somewhere in the context of 5%-10% in add-on.

Whether it comes in Tier 1, Tier 2 or subordinated debt is a matter we can all debate but even if you take the low and high ends of that, we are talking around US$700bn to a US$1trn of that being added on; US$500bn is the number that is potentially outstanding after all the LM exercises etc. But I think the level of capitalisation that we are going to achieve at the end of the cycle is higher than where we were previously, so the outstanding won’t determine what number it’s going to be at the end.

My suspicion is that we are talking about a number at least close to US$750bn in aggregate. Of that number, part will be refinanced and part will be new issue. And it may not be executed in the next two years. It may be the next five years from now.

Johan Eriksson, UBS: I don’t disagree with that level of magnitude as a per cent of risk-weighted assets. But I disagree with the assumption, if I understand you, that that needs to be regulatory capital. I think loss-absorbing capacity to support bail-in risk, for example, allows for significantly more optionality. You can issue three-year subordinated debt but it’s irrelevant from the point of view of the challenges we’re talking about because these are must-pay securities that are only subordinated in liquidation. But they provide bail-in risk capacity.

So I think it overstates the challenge, I would say. And I think the reinvestment of old-style into new-style – not to underplay the challenges there – but I think that that level of capital is more or less outstanding today. I think the challenge is the higher quality under more challenging terms, and the need to continue to raise core equity or reduce risk weighted assets through other means, to release it.

And I think the amount we typically see is something like €500bn for the European system. But I think actually those are relatively old numbers as banks have built Core Tier 1 capital much more quickly than people assumed in the past.

Marc Tempelman, Bank of America Merrill Lynch: It assumes a stable RWA number. RWA valuations may well change, and risk weightings may well change. That would push the number up.

But I’m in the optimistic camp in terms of hoping that the market will accept the amount ultimately that will need to be raised, simply because what’s pushing it down is that I’m not sure that we’ll see a lot of risk weighted asset growth. In fact I’m relatively confident that we’ll see risk weighted asset decline.

Like for like, assuming risk weightings remain as they are, we will see banks stepping out of certain business lines, selling either assets, businesses or whatever. I don’t see many banks jumping up and down looking to build up their balance sheets massively. So that is one additional factor that can play in favour of making sure that the market ultimately accepts, and we find a way of raising all this capital, over the five-year period that I think has been alluded to, in a constructive manner.

IFR: You’ve said the universe of banks that can issue these sorts of instruments is quite limited at this stage, and we’re talking of 1.5% AT1 and 2% Tier 2. How are banks going to meet these requirements? If you’re a small bank, how are you going to go about it? If you can’t sell these instruments, what do you do? Do you die?

Sandeep Agarwal, Credit Suisse: You start with a higher equity base for a start. You run a, thicker equity slice and then slowly leverage it up as the system stabilises.

Johan Eriksson, UBS: Part of the whole premise and objective of the changes is that a very significant part of the banking sector should be consolidated and restructured such that the system is on a much safer footing. This implies that barriers to entry go down, margin resilience improves and margins in absolute terms improve the profitability of the banking sector; although lower in terms of return on equity, the magnitude of profit will go up dramatically once some of the issues we’re still grappling with (and will for several years) subside.

Marc Tempelman, Bank of America Merrill Lynch: But in the meantime, the starting point is you cut your dividend, assuming that the bank is still profitable. Small doesn’t mean that you’re not making profits. And maybe coming back to the comment about reading in the press that we’re a dire place, banks by and large are still making money. So if they don’t pay it out and add to reserves and they’re given time – there’s a question mark how much time they need – the build-up of capital will be a relatively natural thing.

IFR: What about banks massaging RWA?

Marc Tempelman, Bank of America Merrill Lynch: One very easy methods to assess who is possibly playing those games is to divide risk-weighted assets by total assets for every single bank. Some of those outcomes are perfectly natural, because some of the banks have very conservative business models: a pure play mortgage bank, for example, is supposed to have a fairly low number.

But there are others where you can have your doubts around why are the numbers so low. And I suspect that part of the market, if not the entire market, has already taken that into account when comparing capital ratios.

Georg Grodzki, Legal & General: Just to illustrate that, we’re all aware that the FSA is running regular sample tests where an identical loan portfolio of corporate loans is given to banks with the request to use their models to calculate required equity. The discrepancies or the dispersion is massive. I understand there is a discussion underway in the Basel Committee which possibly may result in the banks’ ability to use their own internal models being greatly curtailed because of the temptation to be very aggressive.

From an investor point of view it’s a welcome rollback of the leniency and discretion vis-à-vis the banks that Basel II presented us with and which went far too far. We actually favour even more simplicity; maybe a uniform risk weighting for very different type of assets, including sovereigns because we think any differentiation of risk weightings is debatable and is going to prove itself wrong all the time.

Johan Eriksson, UBS: I completely agree with that. And I think that’s the basis underlying the Swedish changes to mortgage risk weightings. Obviously the historical track record in terms of losses that underlie risk weightings was built on the premise of full employment and incredibly generous social security systems which meant that customers basically had full income protection. Now unemployment is relatively high, and social security is much weaker.

Of course the context for a bank changes and the drivers for loan losses may have changed. So, I completely agree with that. One of my key assumptions for Basel IV will be macro-prudential filters for risk weightings.

Georg Grodzki, Legal & General: But do you really want, as a senior credit investor, to be one of the first ports of call if regulators rethink RWAs and decide they are too low for the future macro environment, word goes round and equity markets seize up for banks? How do regulators then manage the transition to increase or basically maintain reported solvency ratios under a much tighter RWA regime? How do you hedge yourself as a senior debt investor or a hybrid capital investor against not a risk of economic deterioration but a risk of all goalposts changing?

Johan Eriksson, UBS: My view is that you’re amply compensated for those risks. I think the risk itself is fundamentally positive, but obviously there are scenarios where it could cause major issues.

Sandeep Agarwal, Credit Suisse: I agree with that. I think senior creditors are meant to take some risk; the default risk is inherently there. The only other thing that one should think about is the leverage ratio. Because I think to your point, when the control is not there through the RWA, or RWA does not adequately reflect the risk profile of the bank, I think the purpose of the leverage ratio metric is to control that level of arbitrage.

I think we should have the RWA metric, because I think we should differentiate between business models as to how much capital a business needs to run. But I think overall a leverage ratio control, which is a little bit more enforced, will control the dynamic of people arbitraging the system completely.

Johan Eriksson, UBS: With Pillar 3 disclosure the market is perfectly capable of comparing average risk weights by asset class and that ability will improve further. Of course it requires a little work, but it it’s also reported and will be reported in a consistent formula. I think that we shouldn’t forget market pressure on these topics

Oliver Sedgwick, Goldman Sachs: That’s a very fair point. And the fact that there’s more disclosure in the market than there ever has been …

Johan Eriksson, UBS: Too much.

Oliver Sedgwick, Goldman Sachs: Probably. If you roll the clock back to the EBA stress tests, people can talk about where the level was set, whether it was the right level or whether it was positive or negative, but investors got more disclosure out of that on the balance sheets and can compare country by country, and it becomes self policing. The fact that you guys are looking at it extensively suggests that others are. And I continue to hear that.

Johan Eriksson, UBS: But improvements are required. I mean we tried to model Net Stable Funding Ratio and Liquidity Coverage Ratio on banks. And coming from a Nordic background, where things have been disclosed for a longer period of time, you go to French banks or other banks and you can’t even distinguish between corporate deposits and retail deposits.

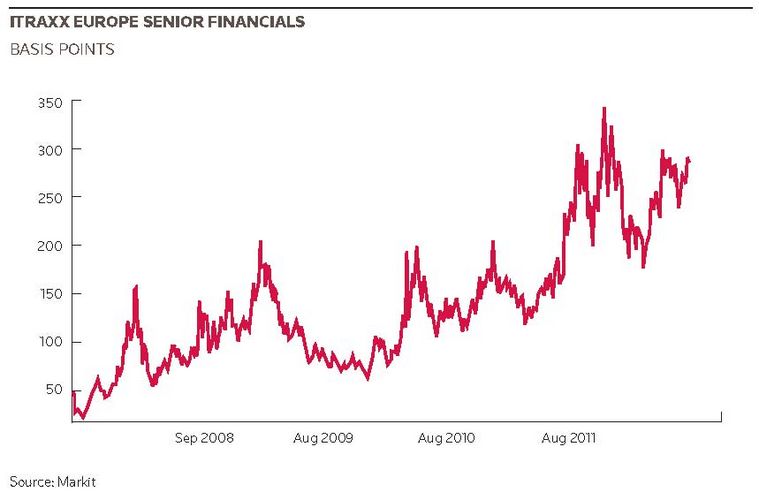

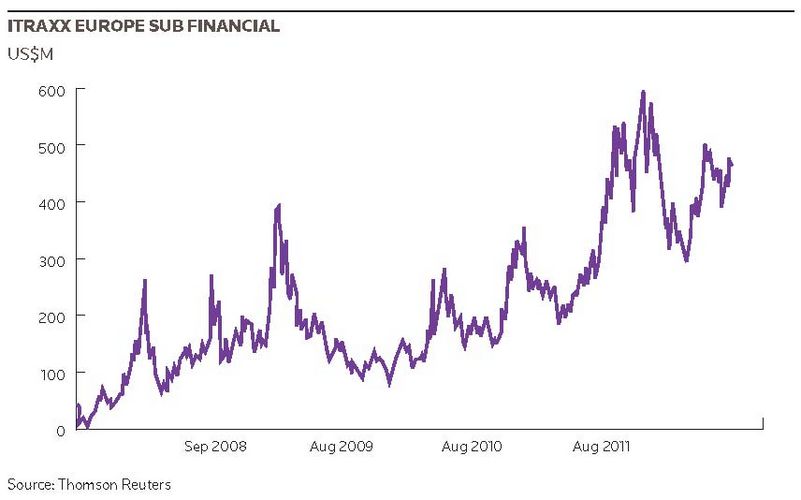

Oliver Sedgwick, Goldman Sachs: What’s interesting is going back to controlling RWA and leverage, you’ve got to a situation where the market’s controlling it because it deems the price of senior, sub and Tier 1. And because it’s so expensive you really think about issuing it. If you can’t issue it then you can’t grow your balance sheet to the same extent.

So there’s already that policing system. And you can see that you’ve got access to funding, it’s actually fairly plentiful, albeit you may not like the price. And I think similarly in a stable market there’s pretty good access for Tier 1 in loss-absorbing form, where there’s that comfort in the business model and disclosure and risk appetite.

So I do think it becomes self policing. You get to a situation where actually the sector becomes very investable, where you’ve got better risk disclosure, better risk management, much truer capital in terms of what the quality is, and policed leverage. And then when you think about senior at 300bp over, versus corporate at sub-100bp, money’s going to flow towards the financial sector. And there is definitely money in the system.