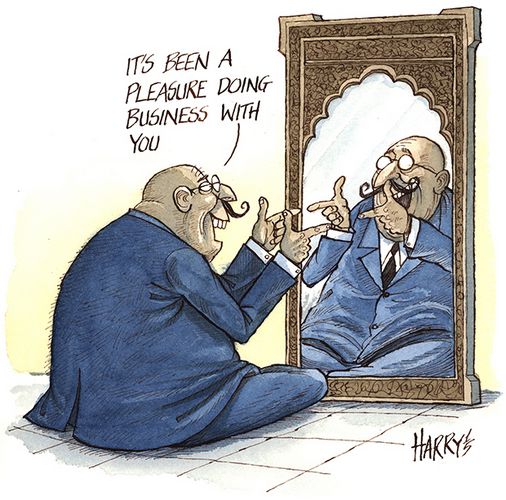

The privatisation plan Narendra Modi touted when he came to power in India 18 months ago has failed to take off quite as the pro-business premier promised. Doubts over his reform agenda are mounting, but are they justified?

Narendra Modi swept to power in the world’s second-most populous country with promises of bold reform. But his privatisation plan, one of the cornerstones of an ambitious campaign to revitalise the Indian economy, has had only mixed success.

To help balance the budget, Modi pledged to raise upward of US$10bn by selling minority stakes in state enterprises to the private sector; he has managed barely half that amount. And many of the part-privatisations were near-disasters, salvaged at the very last moment by state-run investment vehicles.

Most Indian premiers take office with vows to loosen the shackles of the public sector; few succeed. PV Narasimha Rao pushed through a few minority privatisations in the 1990s. But the experience of Modi’s predecessor Manmohan Singh was more typical: arriving with a strong pro-business record, he departed as another defeated bureaucrat unable to tame the crushing, monolithic power of the state.

Just 18 months into his tenure, Modi is already facing questions on whether he, too, is doomed to fail – and even whether he is as reform-minded as he has led the business community to believe.

Modi has certainly eased investment restrictions, allowing foreign invested firms to own up to 49% of local corporates and joint ventures in the insurance, defence and railways industries. Days before a trade visit to London in November, he relaxed rules to help channel more foreign capital into the banking, construction, retail, civil aviation and broadcasting sectors.

Modi says foreign investors now view India as an increasingly solid investment bet, and he may well be right: in the first half of 2015, India surpassed the US and China as the world’s biggest global FDI destination, attracting US$31bn in inward capital, compared with US$28bn secured by China and US$27bn by the US, according to data from information provider fDi Markets.

Yet the premier has more than a little of the autocrat about him, and he has been an ineffective campaigner in India’s lower house of parliament, where the affairs of 1.2bn citizens are legislated with fractious intensity. Even though his Bharatiya Janata Party has the majority there, he has struggled to push through controversial yet much-needed land and labour reforms, and failed to gain traction with a nationwide sales tax that would have boosted revenues and – if the numbers are to be believed – expanded the economy by as much as two percentage points.

“I think investors went overboard on the likelihood of significant reform under Modi when he came to office. It’s not so much that he put the brakes on reform, and more that the process has never really got going”

In the upper house, meanwhile, the opposition Congress party rules the roost – and it is determined to stymie Modi’s reform agenda.

“It’s always easier to get the hard reforms out of the way earlier,” said Mark Williams, chief Asia economist at London-based Capital Economics. That could mean Modi is already on the well-travelled path of his predecessors, from a grand entrance bursting with hopes of reform to a quiet and unlamented exit years later out through the tradesman’s entrance.

Or does a man so often underrated, and so often able to outwit those with more money, connections and political skills, still have a few tricks up his sleeve?

People power

A series of provincial elections stretching through 2016 may hold the answer. Victories could give the BJP control of both houses, handing Modi a gilt-edged chance to pursue an all-out reform agenda in earnest. But the signs so far do not augur success. In one local election in Bihar state in November, a hotchpotch of six minority parties cast aside their ideological differences to join forces and defeat the BJP.

“That election showed that the opposition can beat the government when they form an alliance and create unity,” said Deepak Lalwani, director and founder of India-focused stock consultancy Lalcap. “That could be a big problem for the BJP.”

Many have also begun to wonder whether Modi is fully engaged in the fight. In the BJP’s 2014 election manifesto, the word “reform” was used no fewer than 23 times. Yet the positive influence of private-sector capital was invoked only once, and that only when promising that it would benefit from “close and productive interaction [with] public institutions”.

Firat Unlu, chief India economist at the Economist Intelligence Unit, said people “made a big mistake in assuming that Modi would be a politician who would immediately implement Big Bang-style reforms. It is becoming evident that his policy style emphasises gradual reforms and incremental improvements to institutions, and that he shies away from controversial legislation once the pushback becomes too strong. This is not encouraging in India, where any piece of legislation will always face a backlash.”

Williams at Capital Economics said: “I think investors went overboard on the likelihood of significant reform under Modi when he came to office. It’s not so much that he put the brakes on reform, and more that the process has never really got going.”

Setting Sail

One thing that has never really got going is the Modi government’s privatisation plan. It started with a whimper in December 2014 with the sale of a 5% stake in Steel Authority of India that reduced the government’s share of India’s largest steelmaker to 75%. New Delhi raised just US$275m from the equity divestment in Sail, less than the original target of US$300m–$330m. The sale, which was delayed by three months, was oversubscribed – but only, investors said, because the government set an unambitious floor price of Rs83 per share.

Hopes rose when the state raised US$3.66bn from the sale of a 10% stake in Coal India, the world’s largest coal producer, in January 2015. But that was it on the divestment front for the first half of 2015.

A brace of smaller sales was completed in July and August, with the state earning a little over US$500m by offloading 5% stakes in two specialist financial institutions, the Rural Electrification Corp and the Power Finance Corp.

A far larger auction in the final week of August, involving a 10% sale in Indian Oil Corp, was nearly an outright disaster. Domestic and foreign institutional investors stayed away from the US$1.4bn sale, forcing the country’s largest investor, state-run Life Insurance Corp of India, to ride to the rescue. LIC bought 86% of the 242m shares on offer, bailing out the government – and effectively rescuing the privatisation process (though, given where the vast majority of the shares ended up, it is a struggle to describe the deal as a “privatisation”).

The debacle left investors scratching their heads and trying to decide which party was most to blame: the bellicose Congress politicians determined to destabilise the privatisation process, the trade unions vehemently opposed to any dilution of state power – or the government for failing to properly judge market conditions. The BSE Sensex, a weighted average of the 30 largest shares listed on the Bombay Stock Exchange, peaked in late January 2015 and has been on a systematic, if oscillating, descent ever since.

Yet if the Sail sale was undervalued, many of those that followed were overpriced, impairing interest among private sector investors.

“Either the government has to bring down the price, or they have to cut the size of the stakes they are putting up for sale, at least until market conditions improve,” said Lalcap’s Lalwani.

The levy was dry

Another prime example of the government’s missteps was the failed effort to impose a retrospective levy on foreign institutional investors. The tax, which was to be levied against past capital gains made by foreign investors, was proposed by the Indian tax authorities – and initially defended by the government. It was to have raised more than US$6bn.

Known as the minimum alternate tax, the whole idea was scrapped by Finance Minister Arun Jaitley in September in the face of massive push-back from foreign investors and many experts who considered such a retrospective tax to be against the norms of best practice.

“It was just a straight shot in their own foot,” said one fund manager in Mumbai, who said the episode was “entirely unnecessary and dented investor trust in the government”.

Nor does the future look much brighter. A lack of clarity surrounds a long-planned divestment in Oil and Natural Gas Corporation, which predates Modi’s time in office. ONGC was slated to kick off the privatisation process in the second half of 2014, with the government hoping to earn up to US$3bn by selling a 10% stake in India’s largest energy group. Yet the divestment has been delayed on at least three occasions.

Many eyes are now turning to two upcoming events. First, the sale of another 10% stake in Coal India, announced by Modi in mid-November and set to be completed around January 2016. At current prices that sale – assuming it goes ahead – should net the government US$3.2bn. And second, the next Indian budget, slated for delivery in late February.

“The budget will tell us whether the government is still keen on divestments, and what pace of sales we’re likely to see next year,” said S Subramanian, managing director of investment banking at Axis Capital. Anything less than US$10bn in divestments in the next fiscal year would be, said one Mumbai banker, a “disappointment”.

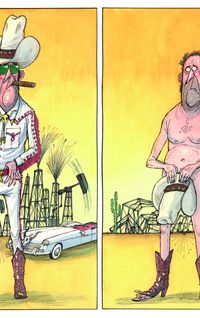

There is one factor that should be working broadly in India’s economic favour – lower energy prices. For a country heavily dependent on oil imports, the lower energy and commodity prices have proven a major boon. Yet they are also systematically undermining the narrower divestment programme.

New Delhi’s success in cutting its fiscal deficit to below 4% of GDP in the Indian financial year to end-March 2015, for the first time since 2009, was aided by a sharply lower petroleum bill. The International Monetary Fund tips growth to come in at 7.3% in calendar year 2015, making India the world’s fastest-growing major economy.

Yet as one door opens, another closes. A smaller import bill has worked against Modi’s privatisation plan, as investors steer clear of anything tainted by association with swooning commodity and energy prices.

“Lower oil prices are a major reason why the share-sale process isn’t going very well,” said Lalcap’s Lalwani. “Long-term, the economic view on India is very positive, but in terms of the privatisation process, the question that stands out is whether there is broad interest in these share sales. And at the moment, the answer is no.”

Still, he remains bullish on the premier’s prospects, saying: “Modi is trying to simplify bureaucracy and deal with corruption at the very top. Cleaning up 65 years’ worth of [corruption] at one fell swoop is not easy.”

To see the digital version of the IFR Review of the Year, please click here .

To purchase printed copies or a PDF of this report, please email gloria.balbastro@tr.com .