High-profile defaults have cast a shadow over Singapore’s bond market, with issuers, bondholders and regulators still grappling to limit the financial and reputational damage.

Singapore’s squeaky clean reputation as a financial centre makes it an unlikely venue for default. But a spate of payment failures in the city state has shocked markets. The question now is whether there can be an orderly solution or if liquidation awaits the defaulting companies in lieu of restructuring.

The first default came just over a year ago, from Indonesian mobile phone retailer Trikomsel, which missed coupon payments on two bonds due in 2016 and 2017 and totalling S$215m (US$150m). Since then there has been a steady stream of missed payments from a range of companies including Swiber Holdings, Pacific Andes Resources Development, Rickmers Maritime and Swissco Holdings.

A sensation of abject fear descended on the Singapore dollar bond market – or specifically in relation to the oil and gas sector – in July when oilfield services company Swiber filed for liquidation.

Swiber subsequently changed its mind, instead applying for a restructuring under judicial management, but the company’s near collapse stunned local market players after it had redeemed S$200m of debt in the previous two months. Investors had assumed it was over the worst, but that proved to be the wrong call in August when the company missed a coupon payment on its S$150m 6.5% 2018s.

Swiber’s viability remains uncertain after its entry into judicial management under the auspices of KPMG, with the fate of around S$550m of debt hanging in the balance while restructuring options are debated. The background atmosphere has not been assisted by the company’s announcement in November that it is the subject of an investigation by Singapore’s Commercial Affairs Department.

“The sense of shock which prevailed when the first default came through a year ago has receded and now banks are addressing the issue of how to absorb the potential losses from the defaults, and how to restructure the capital structure to sustain the business.”

There is speculation that this is linked to an aborted S$710m project in West Africa, which earned Swiber a reprimand from the Singapore Exchange in late October after it failed to fully disclose the conditions precedent for the project.

Since 2015 around S$1.3bn of corporate bonds in the Singapore dollar market have slipped into default, representing about 1% of the total outstanding. As well as the troubled oil and gas sector, the maritime sector can be added to the stream of woe, with soft charter rates squeezing cashflow and compromising debt service. Rickmers put the sector back on the panic radar on November 26 when it defaulted on a S$4.26m coupon on its 2017 bonds after the expiry of a five-day grace period.

“The sense of shock which prevailed when the first default came through a year ago has receded and now banks are addressing the issue of how to absorb the potential losses from the defaults, and how to restructure the capital structure to sustain the business,” said Ada Yu, of independent fixed income specialist SC Lowy in Hong Kong where she works in Asian sourcing.

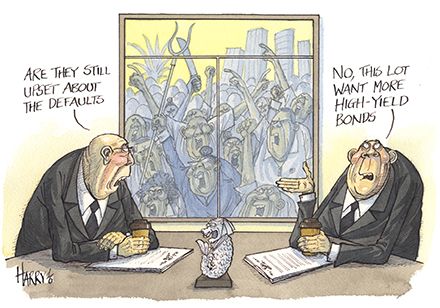

Other market watchers, however, suggest that in the face of plummeting prices in the oil and gas sector and a consequent severe cashflow squeeze in the industry and its ancillary sectors, a large number of operators in Singapore are holding out for a full government bailout.

“There are many moving parts and the question is whether the Singapore authorities will take a draconian line when it comes to moral hazard or whether they regard the companies involved as being of sufficient strategic importance to the Singapore economy that they will move to bail them out,” said a Singapore-based restructuring expert.

Victim of success

The debt defaults have thrown the spotlight on Singapore’s private banking industry and its role in distributing high-yield debt to clients who might qualify as expert investors – they had to have a minimum of S$2m in net personal assets to be able to purchase the debt – but were not expert risk assessors and often bought the positions via leverage extended to them by their private bankers.

“To some extent the Singapore dollar bond market has been the victim of its own success via the attraction, in a low-rate environment, of fixed income products for private retail investors,” said Robert Schmitz, head of debt restructuring at Deloitte in Singapore.

“The explosive growth of private banking in the city state over the past 15 years created the need for product and this in turn allowed companies to issue debt at the top of the commodity cycle. The private banking bid was super-charged via leverage and some of the structures on the debt were questionable.”

The complexity of the growing defaults in Singapore, from a restructuring perspective, is that so much of the debt was placed through private banks in relatively small denominations. A daunting prospect faces the restructuring advisers on the credit side as they try to structure the means for legitimate representation of retail in workouts.

“Typically the issuing companies had around S$50m–$100m in multi-series MTNs which had been sold down to retail, albeit those classified as professional investors, in denominations of S$250,000. The yields on offer were attractive in relation to deposit rates, and demand was there at reasonably short maturities, at two, three and five years,” said SC Lowy’s Yu.

With virtually no market makers willing to make firm prices on the defaulted Singapore dollar debt, analysts at banks and investment firms are having to engage in detailed research and modelling to formulate appropriate secondary pricing.

But for those who are participating in the ongoing Singapore restructuring, either by still holding the paper from initial purchase – as many private bank clients in Singapore are – or those who bought in secondary, such as vulture funds and proprietary desks, the question is one of granular complexity.

The Trikomsel workout, for example, has been the subject of controversy when it appeared at first blush that the conventional capital structure would not be honoured and that an inter-company loan was to be given precedence over the claims of secured noteholders.

So far, none of the issuers that have defaulted over the past year have completed a successful restructuring, in part because individual investors have little confidence that their interests are being respected.

“As prices have slumped in the oil and gas sectors and pressured cashflow, default was inevitable. But it’s not being helped by the fact that, in many cases, there are no market makers for the debt,” said Deloitte’s Schmitz. “Until recently, being largely retail it has been largely a buy-to-hold market. Add to this the fact that there are so many individual retail holders of the paper who have no viable mechanism to negotiate a workout and you have a challenging situation.”

In mid-November the Monetary Authority of Singapore cautioned investors about being too pessimistic about the Singapore bond market, while also reminding them of the risk inherent in every investment proposition. At the same time it proposed some reforms to help strengthen the market, including a measure to force individual investors to opt in to accredited investor status. The MAS is also hoping to help individual bondholders contact each other with a view to joining forces in debt restructurings.

“Unfortunately most retail bondholders are quite often unsophisticated and in Singapore they are now bewildered by the freefall of their portfolios. Then there is the large element of self-fulfilling prophecy. That said, many of these potential workouts are already doomed by complex issues, not by emotions,” said Schmitz.

“In this instance, the more rational approach for the Singapore government would be to support the process by funding professional restructuring advisers to advise bondholders rather than bailing out industries or even noteholders. Coddling the market participants with bailouts only stymies the growth of a major financial centre.”

To see the digital version of this report, please click here