Bankers have long complained that the rules that arose from the ashes of the financial crisis are ill-prepared at best and punitive at worst – and ultimately driven by a spirit of banker-bashing. The election of a US president with a similar view looked set to unleash a wave of creative regulatory destruction. But the early signs indicate that authorities will take a more constructive approach.

Hostility to regulation, and particularly financial regulation, was one of the hallmarks of Donald Trump’s presidential election campaign. He insisted that the Dodd-Frank Act was hurting the US economy and promised to sweep away such rules to supercharge economic growth. He had suggested that around 70% of rules should be cut and many thought he would use his presidency to throw much regulation in the bin.

The US Treasury Department’s June report to President Trump, the blueprint for this regulatory review, underscored this sentiment.

“The implementation of Dodd-Frank during this period created a new set of obstacles to the recovery by imposing a series of costly regulatory requirements on banks and credit unions, most of which were either unrelated to addressing problems leading up to the financial crisis or applied in an overly prescriptive or broad manner,” it said, referring to the banking regulatory reform – officially the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act – that was signed into law by President Barack Obama in 2010.

“Immediate changes, at both the regulatory and legislative level, are needed both to increase economic growth and financial stability,” it said.

But despite some uncompromising language, the substance of the Treasury report is different in tone to the rhetoric of the Trump campaign.

It recommends improving regulatory efficiency and effectiveness by identifying fragmentation, overlap and duplication across agencies; reducing unnecessary complexity; tailoring regulation to account for variations in the size and complexity of regulated firms; and aligning the overall regulatory regime to support liquidity, investment and lending.

Bhawana Khurana, vice-president of financial services client solutions at The Smart Cube, a research and analytics provider, said: “The Treasury has been very constructive in its approach to this process. Its approach has been to look at the costs and benefits of regulations, with a lot of emphasis on what is good about the rules the US already has.”

Wayne Abernathy, executive vice-president of financial institutions policy and regulatory affairs at the American Bankers Association, said: “It’s not about removing rules, it’s about making the rules work better – both for banks and regulators. Some rules actually frustrate each other, and this review will make them interact better.”

While much of President Trump’s agenda feels unprecedented, his regulatory review is actually just the latest example of a system that has always waxed and waned in response to crises, said Oliver Ireland, partner in the banking and financial services practice at law firm Morrison & Foerster.

“The US has a long history of over-regulating in response to crises, before gradually rolling back the rules to find a better balance. The regulatory responses to the Wall Street crash of 1929 and the savings and loan crisis that started in 1986 are two that followed similar trajectories,” he said.

The devil you know

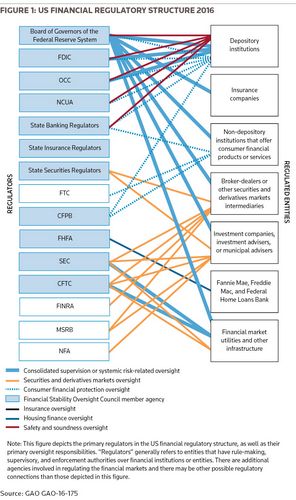

If a new regulatory system were to be built from scratch, nobody would create the current US system. It is hard to envisage a regime overseen by at least 15 separate regulatory bodies ever producing clear and coherent policy. Most financial companies in the US – with the notable exceptions of Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and the Federal Home Loan Banks – answer to at least two supervisors; depository institutions and broker-dealers answer to five or six. The result is institutionalised complexity and confusion – and that is before taking the rules themselves into account.

One US bank CEO pointed out there are six regulators responsible for the Volcker Rule alone – the Volker Rule is the part of Dodd-Frank that stops banks taking “speculative” positions – and called for legislators to give full responsibility to just one.

That is not to say that all regulators should be consolidated into one, the CEO stressed, but for each to have a clearer role, with fewer turf disputes between them. “If people stay in their swim lanes, it’s fine,” he said. “After the crisis every regulator wanted to prove their worth. There’s enough for everyone to do – it’s unrealistic to see fewer regulators.”

The rules themselves layer complexity on top of this tangle of regulatory reporting lines. Having evolved over a number of years, many rules address specific issues, but little has been done to ensure consistency between them. Many were created quickly in the face of significant economic and political pressure, and do not function as intended. By looking at the whole of the rule book and improving individual statutes when possible, oversight can be made more effective, said Abernathy of the ABA.

For the big banks in particular, the status quo is not without its advantages. Having endured a decade of regulatory upheaval, most bankers do not now relish the prospect of more uncertainty. There is no guarantee the new regime will be better than the current one, or how long the next period of transition will take.

Many people at the bigger banks also privately acknowledge that the regulatory burden creates an uneven playing field on which they are better equipped to compete. The head of one large US investment bank said: “Before the financial crisis we had 300 people working in risk. Now we’ve got 1,300. That’s a very high cost that only the biggest banks can easily bear – and a very high barrier to entry to everyone else.”

He added that the leveraged lending rules – which discourage regulated US banks from extending loans where the companies borrowing the money are more than six times leveraged – were especially welcome because they stop the big US banks from damagingly aggressive competition that they otherwise might not be able to resist.

In which case he’ll be disappointed if, as seems likely, the rules are soon effectively withdrawn. Blaine Luetkemeyer, chairman of the House Financial Services Subcommittee on Financial Institutions and Consumer Credit, wrote to bank regulators in November to request they stop enforcing restrictions on leveraged lending. He said some of the guidance given to banks may not be legally enforceable, because rules had been created without first submitting them to Congress for review.

“The immediate regulatory response to the financial crisis came on like Napoleon. The revisions being made to that regulation now can be like the Congress of Vienna. The regime we are building now can be the peace that lasts for generations”

In some cases strict regulations have already transformed businesses in ways that will not be reversed. Ireland at Morrison & Foerster said: “The Volcker Rule was one of the most controversial parts of Dodd-Frank. There are a number of provisions of the Volcker Rule that continue to cause problems, but proprietary trading desks have now moved out of the banks and they are unlikely to be coming back. So for many banks, rolling back the Volcker Rule is not a high priority.”

According to the CEO of one of the world’s largest investment banks, a regulatory roll-back is unlikely to be transformational for top-tier institutions. But it could make a difference for smaller, non-systemic banks, he said.

Another reason that some bankers dread another round of regulatory reform is that it will introduce yet more uncertainty. Indeed, it is the prospect of further regulatory change, rather than the quality of the regulation itself, that prevents banks from investing in systems that will simplify the compliance process, said Khurana of The Smart Cube. Every bank is inundated with data that could be shared with authorities – if only it were in a more digestible form.

“Transforming it into something that can be submitted to them is a challenge and a cost, but investing in systems that automate that process is difficult when they don’t know what information regulators will want in the future,” she said.

“Banks would love to invest in this area, but they can’t until they are confident that the regulation that is in place is going to last.”

A settlement to last

Despite these factors, a majority do favour change. Abernathy senses a mood of optimism among both bankers and regulators, who believe they can agree a settlement that will stand the test of time and deliver the certainty banks currently lack.

“The immediate regulatory response to the financial crisis came on like Napoleon. The revisions being made to that regulation now can be like the Congress of Vienna. The regime we are building now can be the peace that lasts for generations,” he said.

There is actually a high degree of consensus about the need to reform the rules, Abernathy said. “The main differences are the priorities, which vary as much between the banks as they do between the industry and the regulators.”

For example, a bank’s attitude to liquidity coverage ratios (which measure high-quality assets that can be used to meet a bank’s short-term liquidity needs) will vary depending on the level of deposits held. Similarly, attitudes to the leverage ratio (measuring a bank’s equity relative to its debt) vary depending on the level of “riskless assets” it holds. But authorities are under pressure to review both.

Greater clarity around the stress testing introduced by Dodd-Frank and administered by the Federal Reserve may be an even higher priority. Bankers say they are happy to submit to stress tests, but want greater transparency about the specifics on how they are judged. One US bank CEO told IFR that the Federal Reserve was reluctant to share such specifics, for fear banks would reverse-engineer their models to game the system. But change is coming.

Regulators say there is no value in the information they have gathered from stress tests on smaller banks. Amending the rules to ensure the tests only apply to larger banks will therefore free smaller banks from this burden – with no loss to the quality of information being gathered by authorities.

There is also general agreement on the need to trim down the number of ways regulators measure capital, which currently stands at more than 12. Many bankers believe this could be brought down to five or six without undermining the requirement for banks to be well capitalised.

“The ABA felt that simplification of the capital rules should be the priority,” said Abernathy. “But regulators saw stress testing as a bigger priority. We didn’t see living wills as being in play, but regulators did, which is fine.”

The rules requiring living wills for banks were unprecedented, so it was hardly surprising when they experienced significant teething problems. Constant changes to the details left banks struggling to keep up, and it was clear the regulation wasn’t working. The decision to make wills biennial does not roll back the original regulation, but should make it more effective.

Optimists say such reforms will ensure the best elements of the current regime will be kept, while pointless and growth-sapping elements are discarded.

Ireland said: “The rules that came out after the Great Depression included Glass-Steagall, and it took until 1999 to roll that back. And even then they didn’t get rid of all of it. We can’t be sure that it will take that long to reassess Dodd-Frank, but there is cause for hope that it will not.”

If authorities can strike the right balance, the result could be a system that is both safe and vibrant – and one that allows the economy to flourish.

“It is only recently that the return on equity has started to hit that 10% level that attracts new capital to banks,” said Abernathy.

“That is understandable. After the crisis the top priority was making the industry safe. It is only now that goal has been achieved that they could turn their attention to making it sound as well.”

To see the digital version of this review, please click here.

To purchase printed copies or a PDF of this review, please email gloria.balbastro@tr.com.