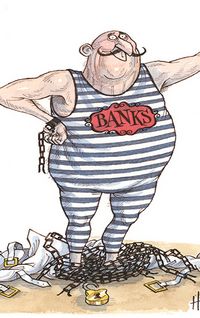

Banks are in a fight for talent with technology, consulting and other firms, but are they ignoring too many students from poorer backgrounds? Some bankers think so, and want the net widened so they can add true diversity.

Do investment banks have a recruitment problem? Bankers these days often complain that the best coders and most talented graduates are turning their backs on finance and opting for career paths where they can earn well while enjoying a better lifestyle.

Yet at the same time, banks have been accused of ignoring talented students because they are from the “wrong” background or don’t have the right accent or look.

Senior bankers admit it’s a problem. They say there’s far less bias in the system than 20 years ago, but know if they can lure more over-achievers from blue-collar backgrounds it may help them in their fight for talent.

“There’s now a business argument, not just a social argument,” said Lee Elliot Major, chief executive at Sutton Trust, a foundation set up in 1997 that aims to improve social mobility in Britain through education.

“Ten years ago, banks tended to look at it through the corporate social responsibility lens because it’s good for society to help social mobility. But now there’s also a core, hard-nosed business reason: can they attract talent in a world that’s much more competitive for the best talent?”

It’s an issue on Wall Street just as it is in the City of London, as evidence mounts that investment banking is slipping down the wish-list for top graduates.

BRAIN DRAIN?

Numerous surveys show students at leading universities are less interested in investment banking than graduates were 20, 10 or even five years ago.

A recent survey of more than 20,000 new graduates at leading British universities showed the number applying to investment banks and finance dropped by a fifth from a year ago, according to High Fliers, a research firm for graduate employment.

At Harvard, the number of MBA graduates heading to investment banks has remained relatively stable at 5% each year from 2012 to 2017, but the number going into finance more broadly was 31% this year compared with 35% in 2012.

Recruiters say banking still struggles with its “men in suits” image. A hard-charging career on Wall Street may have been seen as the place to be through the 1980s, 1990s and early 2000s, but the financial crisis battered that image and prompted a rethink on work/life balance.

Remuneration remains a trump card for investment banks, even if the annual bonus round is now more restrained. Investment banking paid UK graduates more than any other industry in 2017, with a median starting salary of £47,000 and even the lowest end of the expected range well above what their peers heading to, for example, oil and energy, engineering and consulting would get, a High Fliers survey showed.

But the bonus cheque is becoming less important. And technology and other start-up firms can offer equity and a more attractive, nimble and dynamic workplace, recruiters say. Accounting and consulting firms are also seeing a resurgence in applications, and competition is coming from many sectors.

More graduates who join banks are also leaving in their first few years for private equity, hedge funds or a career away from finance.

“We know banking is no longer the top option for many people, but the level of graduates who leave is still surprising,” said a senior executive at a bank in London. He claimed that was despite an improvement in work environment and culture.

But it is relative, and investment banks remain vastly oversubscribed: one industry source said there are still 50–100 graduate applications for each position in London. As a result, they can still afford to be fussy.

Some reckon that may have shielded the industry from changing an outdated recruitment policy, even if the net is being cast wider to a more diverse group of students than in the past.

A senior executive at a bank on Wall Street said his firm had cut back how many campuses it visited and was focusing on some core schools – and some Ivy League names weren’t on the list as it looked for more of a mix. He, and others, said that showed a change in mindset.

BACKGROUND MATTERS

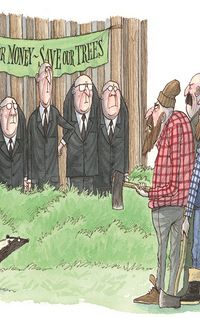

Critics say more needs to be done, particularly in widening the search to people from lower income backgrounds.

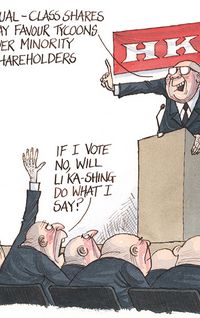

In Britain, 34% of recent intakes and 51% of leaders in the banking sector went to private or independent schools, according to a survey by Boston Consulting Group (hedge funds and private equity firms are estimated to have even higher percentages). Given only 7% of the population attend those fee-paying schools, that is a far outsized proportion.

“We are missing out on a lot of the talent pool in the remaining 93% of people that don’t go to independent schools,” Sutton Trust’s Elliot Major said.

“On current trends it’s likely that the future leaders of the banking industry will probably be just as privileged as those in previous decades.”

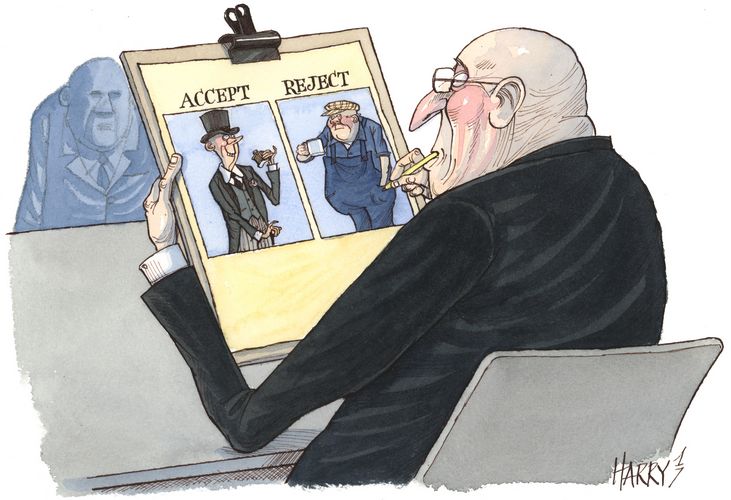

Bankers acknowledge the issue: 81% of senior investment bankers in a survey by Sutton Trust and Deutsche Bank said the way candidates from disadvantaged background present themselves at interviews is preventing them getting jobs in the industry.

That underscores the concern that young people from poorer backgrounds are getting locked out because of their clothes, accent or behaviour. It has been dubbed the “brown shoe effect”, in contrast to the typical banker’s attire of black shoes and suit.

This is often seen once formal pre-screening of applicants gives way to an informal approach by banks in their final decision making – when they assess how someone may fit into a bank, and their “polish”.

“ENSURE INNOVATION”

An earlier, more fundamental problem is just encouraging poorer students to apply to banks in the first place.

“A lot of people, particularly from outside London, don’t see investment banking as for them: they don’t know much about it, the image can be negative, they don’t know anyone working there. So part of the issue is people just not applying in the first place,” Elliot Major said.

Banks also often ask students to apply in their first year of university – favouring those who know about the industry from their background.

Britain’s Social Mobility Commission in a report published in July said another problem is that while investment banks recruit from a wide pool of universities globally, they focus on a small number of elite institutions in Britain – Oxford and Cambridge, London School of Economics, Imperial College London, University College London and the University of Warwick. Students from less privileged backgrounds are less likely to attend those universities.

The Commission also found internship and work experience obtained at university can tilt the odds away from poorer students, as it benefits those whose families and networks know people in the industry.

Banks say they are taking steps to address issues around social mobility.

Sutton Trust has teamed up with Deutsche Bank on a programme to widen access to banking by supporting groups of low and middle-income students to access degrees at the LSE and Warwick. Executives from Goldman Sachs, Barclays and Bank of America Merrill Lynch and the likes of Copper Street Capital and Balderton Capital also sit on Sutton Trust’s board.

Other steps being taken include some banks barring relatives and friends from internships, and widespread use of contextual background in assessments of students, where they weigh results against background to spot the true over-achievers.

Banks are also aware that the industry has lost its shine, and are flagging the variety of roles in the industry, especially in technology. Many of the those jobs are well away from the City of London or Wall Street, such as in San Francisco, Israel, and Curitiba in Brazil, where HSBC has a technology centre.

Britain’s Social Mobility Commission said the benefit would not just be for lower income families, but for the broader economy and the banks themselves.

“It’s important that key sectors … including investment banking use the full range of talent available to them, in order to ensure innovation and entrepreneurialism, and reduce the negative consequences of homogeneity, including group think,” it warned.

To see the digital version of this review, please click here.

To purchase printed copies or a PDF of this review, please email gloria.balbastro@tr.com.