Not so long ago it looked like the classic standalone investment bank would become a thing of the past. But with all the regulations put in place in the wake of the financial crisis, could the standalone model be poised for a comeback?

Even before then-president Bill Clinton signed the 1999 legislation repealing the Glass-Steagall Act, banks had begun transforming themselves into global financial supermarkets. Citicorp and Travelers had already announced their merger the previous year to create what was then the world’s largest financial services company.

Overall, big firms snapped up more than 50 standalone investment banks between 1998 and 2001. And it was not only US institutions doing the acquiring: seeking a foothold in the world’s deepest capital market, European institutions came calling to the United States as well. UBS acquired PaineWebber and Dillon Read; Credit Suisse, which bought First Boston in 1990, acquired Donaldson Lufkin & Jenrette; and Deutsche Bank snapped up Bankers Trust.

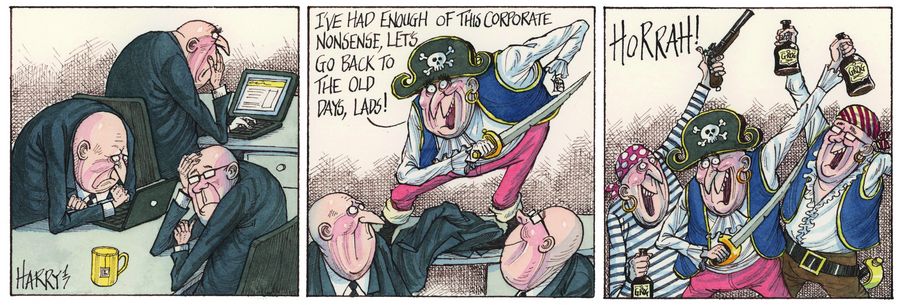

Now, roughly two decades later, some in the industry think it might be time to revisit the idea of the standalone investment bank – not least because post-crisis rules have made the global model less efficient.

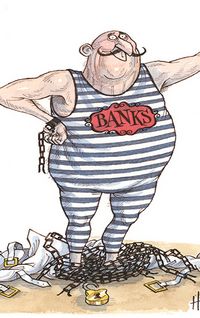

In the US, foreign banks have been forced to set up intermediate holding companies, where they have to hold more capital and submit to rigorous stress tests. UK-listed banks, such as Barclays and HSBC, are being forced to structurally separate out their investment banking operations. In general, it is now more difficult to move capital freely – and thus to operate as a genuinely global firm.

“The regulatory environment requires you to hold more liquidity against one unit of risk in the investment bank,” said one senior FIG banker. “Creating a standalone investment bank would mark a return to the glory days, when a dollar you earn can be put to work in any other part of the world.”

The idea has been appealing to more than a few bankers. In the run-up to his resignation as co-chief executive of Deutsche Bank in 2015, Anshu Jain talked about turning the bank into the “Goldman Sachs of Europe”, a partially spun-off investment bank that would be ring-fenced from Deutsche’s retail operations.

And that same year, Barclays group CFO Tushar Morzaria said the prospect of hiving off Barclays US would give the bank strategic flexibility. The bank’s US operations had “independent boards and their own governance associated with them”, he said. “They genuinely are available for sale.”

Investors, too, have seen the logic of a standalone investment banking institution as a way of unlocking shareholder value.

When Rudolf Bohli, head of activist investor RBR Capital Advisors, launched his campaign in October to break up Credit Suisse, he envisioned three separate businesses – and said he would float the investment bank operation.

“Banks are dinosaurs,” he said.

In the end, the campaign did not find much traction, not least because CEO Tidjane Thiam was already two years into an intensive restructuring plan that involves cutting capital in the investment bank, redeploying into its asset management business and winding down non-core operations.

GAUGING INTEREST

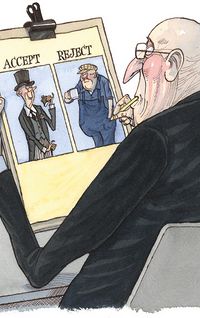

Still, not everyone is convinced that there is value there to be unlocked.

“The question is how much shareholders will be willing to pay for a standalone investment bank,” said the senior FIG banker.

“Ten years ago that price was zero, which is why they all converted to universal banks. You could in theory spin off an investment bank, but the question is whether it can get a sufficient rating. Clients only care if you are a sufficient counterparty credit – and whether you have sufficient equity.”

In addition, most banks moved away from the model in the aftermath of the crisis, opting instead for a more diversified entity combining corporate and investment banking.

In rough terms, monoline or standalone investment banks are defined as those firms that derive at least two-thirds of their revenues from capital markets and wealth management activities.

By that definition, both Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley would still be classified as standalone, though both are also following the over-arching industry trend towards diversification.

Last year, Goldman launched Marcus, a consumer lending platform, while Morgan Stanley has moved heavily into wealth management.

Moreover, according to analysis from Barclays, there is evidence to suggest that diversified banks have performed better than standalone firms since the crisis.

There are, however, exceptions. Jefferies is the only remaining broker-dealer, and its model is the closest to a pure-play investment bank. It offers sales and trading as well as corporate finance, and has expanded aggressively since the crisis; it posted record third-quarter revenues in 2017.

As a broker-dealer it is regulated by the SEC – and as such is exempt from the CCAR stress tests imposed on institutions regulated by the US Federal Reserve.

It also has freedom from other guidelines, such as those that keep its rivals from providing leverage of more than six times. Jefferies has a balance sheet of US$40bn, which enables it to lend to clients, but that is nevertheless small relative to its peers.

“On a small scale you could do it,” said one European bank executive. “But once you get a balance sheet, you become constrained and the cost of capital is high.”

Moelis & Company may be the true poster child for a post-crisis banking model. Launched in 2007 as a one-man operation, it has in the space of a decade grown to be a listed entity with 790 staff in 18 offices across the world. But it has steered clear of sales and trading, offering an advisory-only model that has no capital constraints.

Now that capital is less fungible across borders, and banks are bound by tougher national regulators, institutions are looking for other ways to drive efficiency, such as cross-selling more products to existing clients.

SINGLE ROOF

Meanwhile, the big banks that have merged their corporate and investment banks to increase returns believe that, despite their valuations, the universal banks are worth more than the sum of their parts. In the face of capital constraints, they still see the benefits of keeping activities under a single roof.

In Asia, for example, high net-worth individuals rely much more on capital markets for deals and liquidity than their counterparts in the US. “If you have a ton of billionaires, what they want is their own access to deals and to retain those clients you need an investment bank,” said the head of one firm.

For now, in a climate of record low volatility, universal banks such as Bank of America Merrill Lynch, Citigroup and JP Morgan are thriving. But if volatility returns when rates rise, the case for a standalone investment bank is likely to get stronger.

“The real issue is less about where you are domiciled but how are you going to generate growth,” the head of one investment bank said. “There’s a portfolio of assets not trading at the valuation they should. But that’s a question of execution, not break-up.”

Hans-Joerg Rudloff, the former chairman of Barclays Capital, said: “There’s no doubt that, with the right management, a standalone investment bank could be very profitable.”

To see the digital version of this review, please click here.

To purchase printed copies or a PDF of this review, please email gloria.balbastro@tr.com.