To see the digital version of this report, please click here

There are new features available.

View now.

Search

There are new features available.

View now.

Search

It has taken the Chinese authorities some time to settle on an English name for President Xi Jinping’s signature trade and development policy. What started in October 2013 as the Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road and was labelled One Belt, One Road, or OBOR, at first is now officially the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). What was never in doubt, however, is the sheer scale of the plan. The parallel development of an overland trade route from China to Europe via Central Asia and a maritime link to the Mediterranean via...

After the latest run of hot IPOs, there is no doubt that technology is now the Asian equity investor’s sector of choice. The listings of ZhongAn Online P&C Insurance and China Literature in late 2017 caught the imagination in Hong Kong, with hundreds of thousands of retail investors piling in with orders. Investors in the region are crying out for more opportunities to invest in fast-growing businesses, even welcoming companies that have yet to turn profitable. The surging interest makes it clear why Asian stock exchanges are so keen to attract...

The virtual currency world will remember 2017 as the year in which this niche and somewhat shadowy industry exploded into the public consciousness. The seemingly day-by-day rise in the price of bitcoin and the explosion of the number of smaller rivals, known as alt-coins, created a spate of headlines. Virtual currency also barged its way into the corporate finance world through the much-maligned initial coin offering (ICO). The concept of the ICO is one that is so far not being taken seriously in traditional corporate finance circles. The...

A curious inversion of the “shoeshine boy” scenario now applies to global asset prices. That apocryphal story involved Joseph Kennedy – the rich father of the future president of the United States – realising it was time to exit the stock market just prior to the 1929 crash when the young lad shining his shoes in New York blurted out recommendations on which counters to buy. Nowadays it’s easy to envisage the same scenario, in relation to the idea that everything from stocks to bonds to ETFs to cryptocurrencies is absurdly overvalued. But the...

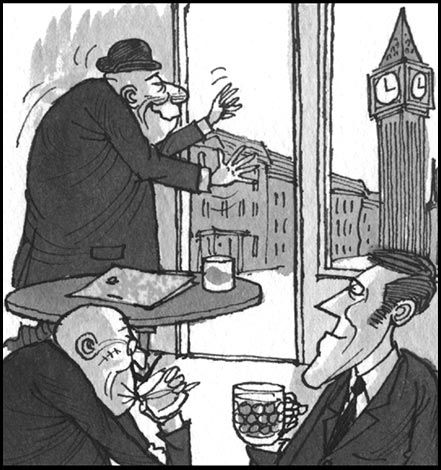

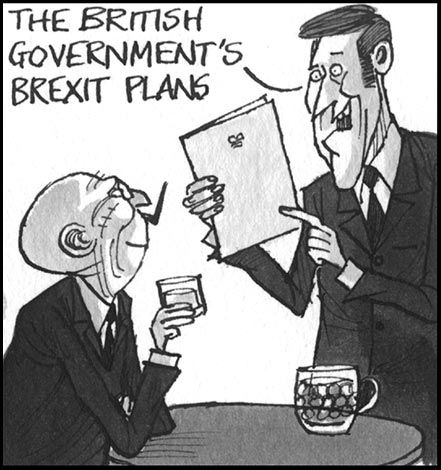

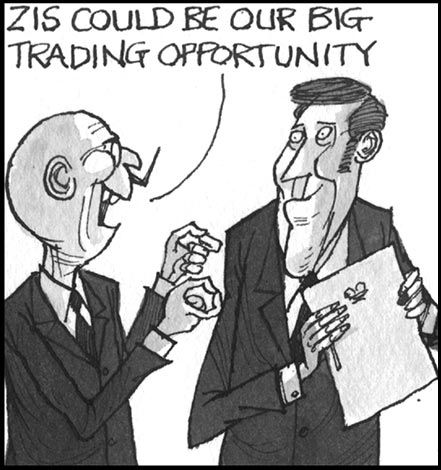

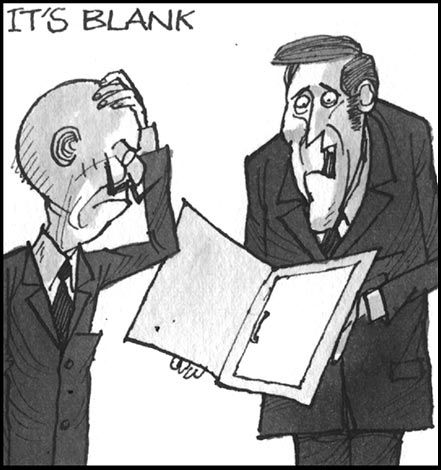

The year in cartoons Highlights of the year in black and white To see the digital version of this report, please click here

The year in numbers Review of the year 2017 To see the digital version of this report, please click here

To see the digital version of this report, please click here

To see the digital version of this report, please click here

To see the digital version of this report, please click here

Alternative definitions of the year’s buzzwords 364-day notes Means by which issuers can sell offshore bonds when the Chinese government really doesn’t want them to do so. (See ‘Tempting fate’.) Agnostic What you pretend to be as a loan banker when you lose business to your bond colleagues or vice versa Alt coin Extremist political group in favour of alternative digital currencies Australian housing crisis Prediction for 2016, 2017, 2018 from London-based “experts”, to be followed inevitably by a banking crisis Balance sheet velocity When...

All websites use cookies to improve your online experience. They were placed on your computer when you launched this website. You can change your cookie settings through your browser.