The growth of Asia’s institutional investor base is helping justify some rich valuations in the region’s capital markets, and reshaping the way deals are done in the process. Will the trend continue into 2018?

A curious inversion of the “shoeshine boy” scenario now applies to global asset prices. That apocryphal story involved Joseph Kennedy – the rich father of the future president of the United States – realising it was time to exit the stock market just prior to the 1929 crash when the young lad shining his shoes in New York blurted out recommendations on which counters to buy.

Nowadays it’s easy to envisage the same scenario, in relation to the idea that everything from stocks to bonds to ETFs to cryptocurrencies is absurdly overvalued. But the modern day shoeshine boy doesn’t tell you what to buy: he tells you to get the hell out.

It’s common knowledge that asset prices are at stratospheric levels on a variety of measures. One could look at the Shiller P/E ratio, which suggests that US stocks are as overvalued as they were just prior to the crash of 1929 or during the dotcom bubble.

Cryptocurrency bitcoin smashed through US$15,000 a coin in early December with such savage speed that not owning that mysterious unit of exchange has become the ultimate hindsight trade de nos jours.

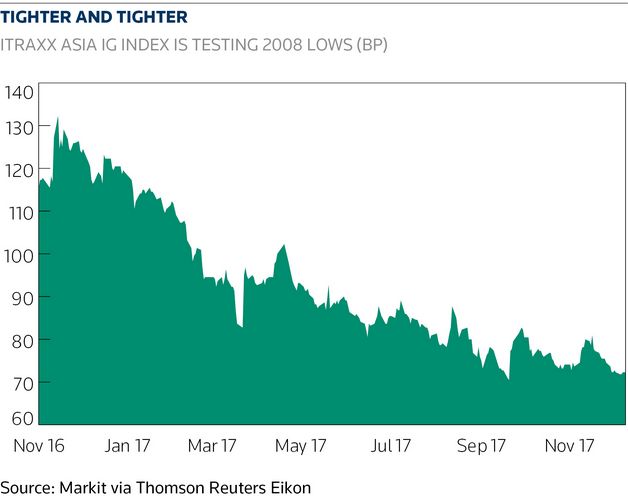

Meanwhile in Asia, credit spreads have returned to levels not seen since just prior to the global financial crisis of a decade ago. The iTraxx Asia ex-Japan Investment-Grade Index, which measures five-year CDS, has contracted by 90bp over the past two years, even in the context of a 50bp increase in five-year US Treasury yields, to just below 75bp as this report went to press.

Against this backdrop, there is talk of global financial crisis part two. A large coterie of professional market players are of the “not if but when” mindset, and the game is to guess what might precipitate the correction.

War with North Korea is the favourite contender among doomsday merchants, with a debt crisis in hyper-leveraged China also a frequently cited catalyst. An overly aggressi.ve unwind of Japan’s super-easy monetary policy also gets a mention.

But how would Asian credit fare should a rerun of the GFC – heaven help us all – play out? One could only assume that the issuance party which has seen annual volume in Asian G3 primary markets surge from around US$25bn a decade ago to around US$350bn this year, will be brought to a halt.

If primary deal size is a measure of “irrational exuberance” – to borrow former Fed chairman Alan Greenspan’s infamous parlance – then 2017 took the cake.

Blockbusters such as Postal Savings Bank of China’s mammoth US$7.25bn trade or Alibaba Group’s US$7bn have become objects of insouciance in the midst of massive oversubscription and rock-steady secondary trading.

It would be fair to assume that anything that resembled a “GFC part 2” would bring this Asian issuance bonanza to a halt. But it is becoming fashionable among both the buyside and sellside in Asia to suggest that the region’s credit markets are likely to weather any generalised financial turbulence better than most other blocs, and particularly if the correction has an orderly semblance on the way down.

TEFLON-COATED

One example to justify this view was the sanguine reaction to default by China real estate developer Kaisa Group Holdings in 2015. In previous years, so the thinking goes, such an event would have slammed the issuance window firmly shut, perhaps for months.

Asia’s primary bond markets now seem Teflon-coated. If an eyelid was batted when Kaisa renegotiated US$2.5bn of debt, it was only for the primary market’s equivalent of a nanosecond. It was business as usual almost immediately.

It’s reasonable to read this as a measure of just how mature Asian primary markets have become. The days when an Asian G3 new issue had to be anchored by the US institutional bid are long gone, and the proportion of trades taking the 144A route has fallen markedly.

The swelling coffers of the life insurance and pension fund industries, and the growth in assets under management at the private banks have made Asian investors so liquid that the region can handle primary issuance in size on its own, thank you very much.

Asian high-yield is no longer the freak show it was, and bank capital deals can cross the line with ease – even when the chance of a writedown presents an eye-watering credit proposition.

But during this maturation process, the landscape of the Asian credit markets has changed radically from a human capital perspective. The mass headcount cuts have produced client coverage of the skeleton-staff variety and “juniorisation”, whereby young and inexperienced (and cheap in the pay stakes) deskers find themselves assigned work which previously would have been handled by seasoned veterans.

A frequent gripe on the buyside is that the key point people in a primary deal are nowadays tough to reach and do not always inspire confidence.

The swelling coffers of the life insurance and pension fund industries, and the growth in assets under management at the private banks have made Asian investors so liquid that the region can handle primary issuance in size on its own, thank you very much.

Indeed, such is the grumble about coverage that institutional buyers are increasingly hiring boutique advisers to make the key calls on new issuance: the incumbents at the selling banks are not to be trusted.

I recently met up in Singapore with a former colleague from my days in the early 1990s working in fixed income in London. He earns a living nowadays as a trainer in swaps and derivatives for investment and central banks, and he noted the stark – it seemed to me almost ghoulish – contrast between how things used to be on the trading floors of yesteryear and how they are now.

Rather than yelling out to the swaps trader across the floor or into the squawk box for a price in five-year yen/dollar, the method now is to send him an email asking for the same.

The reason is compliance: you have to leave a trail of record for everything you do. I haven’t been onto a trading floor for quite a few years, but he tells me now the atmosphere is something akin to a library or a church.

I somehow doubt that enhances the sales process, but the strictures of Dodd-Frank and the general atmosphere of institutionalised paranoia that has introduced this new modus operandi seem irreversible.

That it induces profound nostalgia in those still left on the trading floor from the Wild West days of the eighties into the noughties is inevitable. It suggests, perhaps, that the ability to feel the mood of a market while supposedly participating in it has vanished. I believe there’s a cost in that – it may even explain the curious death of volatility in the global bond and credit markets.

But then again, people go about their lives rather differently nowadays thanks to their smartphone apps and social media feeds. Which brings me to the logical conclusion of the new way of doing things in the credit markets: fintech.

UBER MOMENT

I have been sceptical in the past in the pages of this publication about the viability of fintech in the fixed-income markets. That was because, at least as far as the illiquid secondary bond markets are concerned, there is a quintessential element of discretion at the core of these markets.

Traders with long positions to axe are wary of advertising the fact to all and sundry. And there is the quid pro quo which often motivates the purchase of an illiquid bond from a valued customer in return for the cross-sell, perhaps of a difficult-to-shift “worker” new issue.

But maybe the bond market’s “Uber moment” has arrived. If the collapse of bond tech company Bondcube, which was established by a former Citigroup trader in 2012 and went into liquidation three years later, left a sour taste, it didn’t deter others from hoping to be the bond market’s Uber.

There are some startups in Asia, for example, which harbour that ambition. One is BondeValue, which aims to provide pricing transparency for a universe of around 1,500 bonds via smartphone app. The aim is to eventually provide transaction capability.

Meanwhile, independent fintech firms are pushing into the syndication process with software to streamline the cumbersome process of primary bond execution, which has hitherto involved a logjam of emails and conference calls to confirm and reconfirm orders and weed out duplication.

A debt market veteran recently suggested to me that the traditional function of the flesh-and-blood syndicate banker will all but disappear within the next three years. Self-learning computers will increasingly be the entities placing orders for a new issue, rather than a bloke at the end of a telephone.

It underlines the sense that the human element is about to become surplus to requirements in capital markets. And with that, presumably, human error will go, too. Perhaps it really is different this time, and the new ways of going about things will eliminate the seeds of destruction that have bedevilled markets over the centuries.

We may well find out in 2018 if Asia’s progress and creeping automation has made its markets any more robust. But with robots taking over the task of shining our shoes, the danger signs are becoming harder to spot.

To see the digital version of this report, please click here