The amount of money investors are recovering from companies that default on their debt has fallen at a sharper rate this year than during previous credit cycles, potentially heralding a structural shift in debt markets, according to a new report from Barclays.

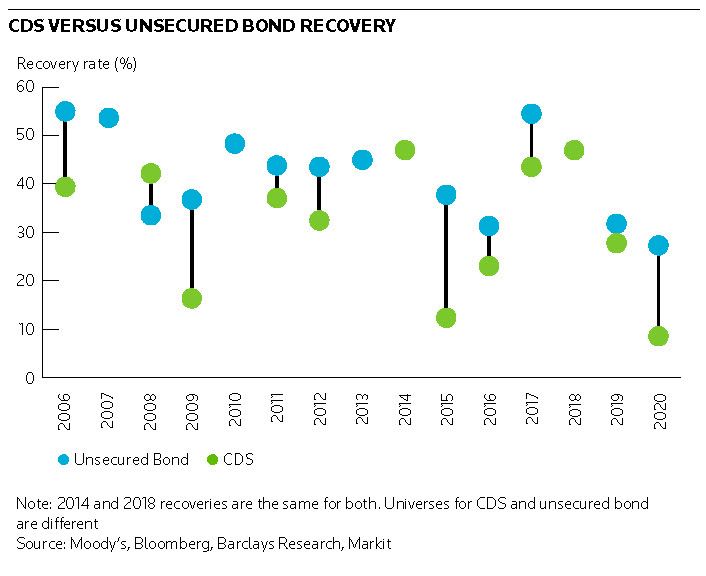

CDS recoveries have sunk “alarmingly” to an all-time low of nine cents on the dollar in recent months, while loan recovery rates also fell further than expected to 48.5 cents on the dollar at the end of July – nearly 20 cents below the long-term average, Barclays said.

The drop in CDS recovery rates could foreshadow a further decline in recoveries for unsecured bondholders, according to Brad Rogoff, the author of the report, who also identified discrepancies in the amount of money different types of loan investors are receiving as another troubling development that could trigger changes in this corner of debt markets.

“Overall recovery rates [are] potentially signalling an important shift in market structure,” said Rogoff, who heads credit research at Barclays.

“Most investors had expected lower recoveries, but [these] two trends are causing even more concern.”

Corporate defaults have picked up after the spread of the coronavirus forced large sections of the global economy into lockdown earlier this year. Default rates for US speculative-grade bonds rose to 8% for the 12 months to the end of July, according to Moody’s, nearly double the level at the end of 2019.

RECORD LOW

The recovery rate for unsecured bondholders has sunk to 27 cents on the dollar, lower than during the credit crisis. The first nine CDS auctions this year, meanwhile, have produced a record low average recovery level of just nine cents, Barclays said.

That sharp drop in CDS recoveries is probably a result of both the design of the CDS auction process used to determine payouts, and an increase in distressed debt exchanges.

Distressed debt exchanges don’t trigger CDS in the US. But they can still alter a company’s debt profile significantly by moving some lenders further up the capital structure in exchange for relief, while leaving a smaller set of unsecured claims further down the pecking order.

Distressed exchanges have accounted for 40% of defaults since 2008 compared with 12% before then, according to Barclays' analysis of Moody's data. Average recovery rates for distressed exchanges appear high at 62%, but there are often some remaining unsecured bonds with “minimal [value] in case of future default”, Barclays said.

Chesapeake, California Resources, Neiman Marcus and McClatchy all had debt exchanges prior to filing for bankruptcy this year, leaving some low-value unsecured bonds to be delivered into CDS auctions. The average recovery for those CDS was just 2.4 cents on the dollar, Barclays said.

More broadly, nearly 20% of the high-yield bond market is in some way secured, up from 6% 20 years ago, meaning unsecured bondholder "recoveries are getting squeezed on both ends, with more debt ahead of them and less behind them".

“We expect losses for CDS and bond investors to remain higher than at similar points in previous default cycles because of structural changes in the high-yield market,” Rogoff said.

LOAN DIVERGENCE

Loan recovery rates fell to 48.5 on the dollar in July, from an average of US$67 in recent years. Rogoff said a decline to US$55–$60 had been expected for many reasons, including higher leverage and more secured debt.

But he said the divergence in recoveries among different loan investors was cause for concern. CLO investors, which own around 60%–65% of the institutional loan market, can often find themselves worse off as a result of restrictions preventing them from holding lower-rated or defaulted loans.

That contrasts with hedge funds and distressed funds that can provide debtor-in-possession financing to struggling companies, giving them first priority over collateral and allowing these investors to improve recovery levels on their existing debt.

In Acosta and JC Penney, for example, CLO investors received recoveries 20 to 30 points lower than lenders that provided DIP financing.

“Hedge funds and other distressed investors have been able to exploit the inability of CLOs to provide new-money capital and receive better economics as a result,” Rogoff said.

One solution could be to give CLOs a limited ability to participate in restructurings with new money and potentially to receive equity securities, the report said.

“CLO and loan indentures likely need to be amended to make recoveries more uniform and reduce downside for certain holders,” Rogoff said.