HSBC and NatWest Markets are both looking to sell multi-billion pound derivatives portfolios as part of a broader scaling back of their fixed-income trading divisions, according to sources familiar with the matter.

The two UK banks, once formidable competitors in this area, are focusing on offloading long-dated interest-rate derivatives positions in the UK and Europe that consume large amounts of capital, the sources said, with banks including BNP Paribas, Citigroup, Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan and Morgan Stanley touted as potential buyers.

The plans lay bare the marked differences in investment banks’ approaches to their rates trading businesses, where banks buy and sell bonds, derivatives and other products linked to interest rates, reinforcing a clear dividing line running down the industry. NatWest and HSBC are the latest in a line of predominantly European banks to scale back these activities after the post-2008 crisis regulatory framework and a seismic shift in interest rates combined to dent profitability.

That contrasts with a cluster of mainly US banks retaining significant global rates trading operations, which have enjoyed a meaningful bump in revenues this year as market volatility has increased.

"The consolidation in market share across the top five or six banks in rates has been quite significant. Only a few banks have decided to maintain global product rates capabilities, while others decided to have a much more regional focus," said George Kuznetsov, a partner at McKinsey. "The reality is it's very hard for banks to make a high return on equity and maintain stable margins in rates outside of their home market."

HSBC and NatWest have each outlined comprehensive plans to slash risk-weighted assets, with long-dated, capital-intensive rates derivatives positions seen as a main area of focus (SEE BOX STORY).

NatWest is in talks with JP Morgan to buy some of the interest-rate derivatives exposures, according to sources. BNP Paribas, Citigroup, Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan and Morgan Stanley are among the potential buyers for HSBC’s derivatives positions, sources said. The sales could come in the form of large blocks of trades as well as broken down into smaller chunks and even individual client trades, sources said.

Spokespeople for BNP Paribas, Citigroup, Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan and Morgan Stanley declined to comment on the potential sales.

“We do not recognise this speculation," a spokeswoman for NatWest said. "We do have some long-dated uncollateralised exposures, but the main focus is reducing inefficient capital related to historic activity in our collateralised portfolios, particularly with interbank and large FI names. NatWest Markets is a strategically important part of NatWest Group".

Bumper period

The divestments come at a time when banks’ fixed income-trading units are enjoying their best spell in years following a prolonged period of decline, particularly for rates desks.

A more punitive regulatory framework, the low interest-rate environment and increased electronification have combined to crimp the profitability of this mainstay activity, with banks consistently struggling to hit investment-bank return targets.

Not that this challenging backdrop has discouraged all firms from investing in their rates desks. Morgan Stanley cut its fixed-income division by 25% in 2015 after revenues in these markets declined. But the US bank has recently been re-building, hiring around half the number of staff that left fixed income back then.

“Post the financial crisis, rates franchises across the Street have been impacted by new liquidity and capital rules, which have put pressure on returns. At Morgan Stanley our leadership has seen through that and taken the view as a full-service, integrated investment bank you need to have a credible rates business as one of your core businesses,” said Jakob Horder, head of macro sales and trading at Morgan Stanley.

BNP Paribas is another bank to have bucked the trend, growing rates trading in recent years. Joe Squires, co-head of G-10 rates for EMEA, said the French bank's management has looked through any short-term noise to commit to the business for the long-term.

"The rates business is tough from a return on equity perspective – the costs of running the business are high. Market shares have consolidated towards the top players and it's harder for marginal players to make hay,” said Squires. “With market share and scale comes profitability and return on investment in terms of the costs of running a business.”

Scaling up

Bankers agree that meeting return hurdles in rates trading – which often only produces a return on equity of 6%–8% – only becomes trickier as the business shrinks. It's no coincidence that those to have stayed the course – including US giants Citigroup, Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan – have relied on economies of scale to keep things humming along.

Another common trait: viewing rates as part of a broader portfolio of complementary markets activities – an essential offering for their corporate, government and institutional client roster – that helps bring in other business such as bond underwriting mandates.

"Citi is good at incentivising different businesses to maximise returns on all of the various metrics, while also thinking about the sum of the parts. We can do that because of the breadth and scale that we have,” said Deirdre Dunn, co-head of global rates at Citigroup.

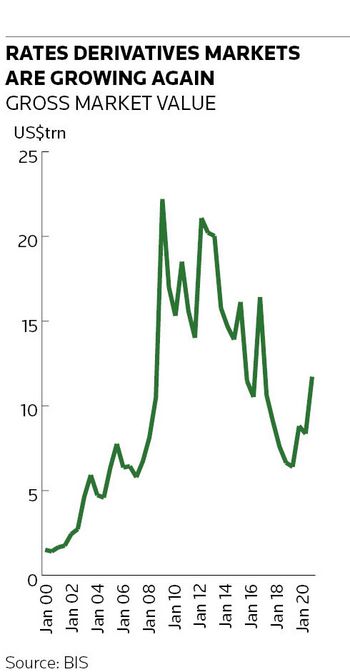

That kind of scale can pay dividends in years of extreme market turmoil such as 2020 when central banks stepped in to backstop markets, interest rates plunged and investors flocked to haven assets like government bonds. Rates divisions have been at the forefront of the fixed-income revival thanks to this volatility sparking a frenzy of trading activity and record bond issuance volumes spurring a wave of client hedging trades.

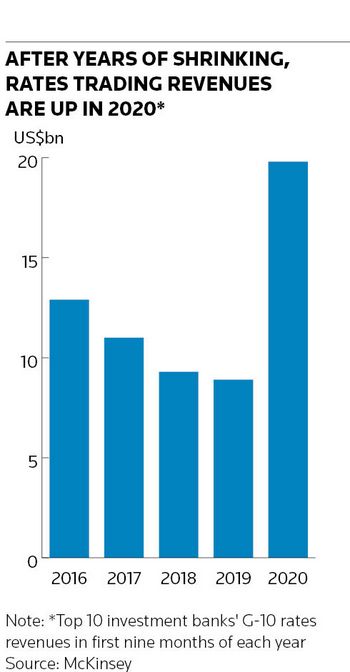

Trading revenues at the top 10 investment banks’ rates divisions have jumped to nearly US$20bn in the first three quarters of 2020, up from US$8.9bn during the same period last year, according to McKinsey.

“The rates business has a degree of cyclicality and can provide strong returns if managed well with the right time horizon,” said Horder.

That kind of performance may give pause to the banks that have slashed back their rates desks. Still, bankers aren’t kidding themselves that 2020 heralds the start of a new golden period for the rates business. After all, the backdrop of low interest rates and tough regulation remain as challenging as ever.

“It’s been a great year for rates businesses,” said McKinsey’s Kuznetsov. “But there are questions around the sustainability of that growth – 2021 is expected to look closer to 2019 in revenue terms.”

BOX STORY – DERIVATIVES IN FOCUS

NatWest Group has been shrinking its markets business since the UK government bailed out Royal Bank of Scotland – as it was then known – in the 2008 financial crisis. That has accelerated again since chief executive Alison Rose said in February she planned to reduce risk-weighted assets in NatWest Markets by about 50% to £20bn.

"We announced a strategy in February to refocus the business to align it better with the needs of our corporate and institutional customers and we have made good progress. We are committed to, and will continue to develop, our capability in currencies, fixed income and capital markets activities, focusing on what we do best and matters most to our customers," a NatWest Markets spokeswoman said.

HSBC said earlier this year it would shed US$100bn of RWAs by the end of 2022, with a large portion of those cuts expected to land on the rates division.

Banks such as Credit Suisse and UBS have in recent years focused on cutting back capital-intensive interest-rate derivatives when looking to reduce RWAs and boost profitability. The biggest headache for these firms has tended to be long-dated, uncollateralised swaps exposures. The regulatory framework developed after the 2008 financial crisis heavily penalised these types of trades, which clients such as major corporations and government entities use to manage their interest-rate risk.

Baking these costs into the price of new trades was easy enough. But the long-dated nature of the business – 30-year swaps are commonplace – left banks with a large overhang of business that would act as a drag on returns for years to come. Meanwhile, the plunge in interest rates – 10-year German bond yields weren’t far off 5% in 2008; they’re now at –0.5% – radically shifted the value of old trades struck at higher levels and increased the cost of carrying them.

Shifting exposures to some sort of “bad bank” and looking to unwind or sell them has become common practice. But the shrinking pool of potential buyers means banks offloading these portfolios now may find they can’t be too picky when it comes to accepting a price.

Such sales are also complex to pull off given that the banks involved must secure consent from counterparties on the other side of trades. Would-be buyers say it’s worth the effort, pointing to a variety of potential benefits such as building new client relationships.