The adoption of Article 6 at the UN's COP26 climate meeting in Glasgow earlier this month has established rules for global carbon markets that will allow billions of dollars of investment to flow into voluntary carbon markets and the next six months will be critical to get the infrastructure and standards in place to allow new financial products to flourish.

The focus now is on implementing Article 6 and defining the types of projects that can be used to create liquid, tradeable products and operational markets.

"Carbon credit markets have been recognised officially and legitimised by the Article 6 process, which I think is great news," said Chris Leeds, head of carbon markets development at Standard Chartered. "It has created a framework but of course, like everything related to international carbon agreements, there are a lot of questions still unanswered."

Article 6 was originally devised as part of the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change and relates to international carbon markets and trading emissions reductions. It set rules for regional compliance or mandatory markets and crucially created a system that will avoid double counting offset emissions between countries. Each carbon credit is equal to one tonne of reduced, avoided or removed CO2 and is retired after it is purchased.

The agreement at COP26 will allow emissions reductions to be more efficient and ideally faster by setting up carbon crediting mechanisms that governments can use to meet targets under their nationally determined contributions. The UN will certify which carbon projects can generate credits for governments.

Although voluntary markets are not regulated by Article 6, the crediting mechanism is also expected to unleash a surge in the voluntary market as countries can make "corresponding adjustments" that remove double counting and lend credibility to smaller-scale voluntary offsets.

The voluntary market is worth more than US$1bn and forecast to increase to US$50bn by 2030, according to the Taskforce on Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets, which was established last year by Mark Carney, the UN special envoy for climate action and finance.

Carney is calling for voluntary markets to grow to as much as US$100bn, which could potentially close the gap between what governments can currently deliver and the global emissions reductions required to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement to limit global warming to two degrees Celsius.

Grey areas

The key questions centre around the quality of the carbon credits being generated from projects that reduce or remove emissions and what companies that use them can claim. Offsetting remains controversial, and is still seen by many as a licence to continue to pollute.

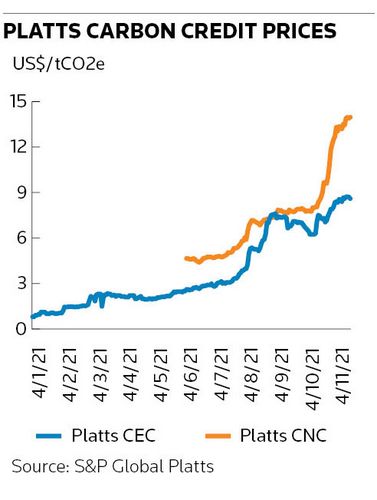

"There still isn't a consensus or anything conclusive that's coming out of Article 6 around the quality of carbon credits. There's still an enormous range of prices and projects out there and I still really don't know which ones are good quality or not. The other thing is the quality of demand – what can you claim around carbon credits?" Leeds said.

These questions could be addressed in the first or second quarter of 2022 as standards are developed, including the TSVCM's Core Carbon Principles that will identify high-quality carbon credits, and supervisory bodies are put in place, such as the Voluntary Carbon Markets Integrity Initiative, as the push to standardise the market gathers pace.

“There could be some big movements in 2022. A lot will be happening very quickly," Leeds said.

Getting it right is vital to creating international cooperation in a new market that could help to move money at scale from the global north to the south and finance much-needed adaptation with a 5% levy at issuance that would flow to a fund to assist developing countries.

Investors cautious

The agreement at COP26 stops short of creating a carbon adjustment border mechanism to establish a global carbon market and a floor on the price of carbon, which investors still see as the most powerful catalyst for the transition to a low-carbon economy.

"I'd have liked to see more to be honest on the carbon side," said Navindu Katugampola, global head of sustainability for Morgan Stanley Investment Management. “The outcome of COP means that the carbon pricing lever isn’t quite as strong as it might have been.”

The lack of progress on a single global carbon market is unlikely to stop banks and investors continuing to work on new carbon products and infrastructure that include indices, exchanges, cryptocurrencies and ESG debt. But serious progress is unlikely until the new standards and supervisory bodies are in place. Without that, reputational risk may be too great.

"This is still not a homogenous market that most risk officers would recognise and would be comfortable signing off on within a bank. The Core Carbon Principles will help to develop high-quality carbon credits," Leeds said.