The true effects of Brexit on Europe’s capital markets have yet to be felt, but they will be far-reaching as divergence accelerates in 2022 and the EU takes a tough line on cross-border arrangements.

![]()

A year on from the UK officially leaving the EU, banks are preparing for greater upheaval as the European Central Bank begins to take an increasingly tough line towards banks moving more staff and infrastructure to the European Union. But nearly six years after the 2016 Brexit referendum – and after a huge amount of effort to position the banking industry for a brave new world – it is far from clear what is to come.

“Brexit has just started. All banks were reasonably well prepared for the end of 2020 Brexit deadline but a lot of the work is still ongoing. The European project will continue to evolve over the next five to 10 years, with continued progress on banking union and capital markets union,” said Kristine Braden, Citigroup’s Europe cluster head.

Perhaps what hasn’t happened is most obvious. The UK has not embarked on a buccaneering wave of deregulation; the EU has not grabbed a swathe of jobs and activity from the City. It’s all been much more subtle.

But there have been changes. Because the EU refused to grant to the UK the equivalence it provides to most other financial centres, capital, people and products have shifted to other locations.

London has lost its mantle as a global hub for derivatives trading, with trillions of dollars worth of derivatives trading leaving the City to head for EU venues but also to US swap execution facilities.

US SEFs accounted for 42% of on-venue euro interest-rate swap volumes at the end of June, according to post-trade firm Osttra, up from 34% at the end of March and now rivalling EU venues as the top trading hub for such activity.

The pain has not all been one way, however. The ending of equivalence has also damaged some EU banks by preventing them from taking a share of the significant amount of activity that remains in the UK. That’s because both UK and EU regulators require foreign banks to establish fully capitalised subsidiaries in their jurisdictions if they want to connect to local trading venues. Banks like BNP Paribas, Deutsche Bank and Societe Generale, which operate branches instead of subsidiaries, are now cut off from UK derivatives venues.

One area where something like the status quo has survived is clearing. In November 2020, the European Commission extended the ability of European banks to use London’s clearing houses or central counterparties for derivatives until 2022. This was seen in some quarters as a reprieve for London but in reality it was also a move that was as much in the interests of the EU as the City.

One senior banker said: “The EU is extending CCP equivalence in its own interests, but they’ve made it clear they want this to be temporary and they want a clear business transition. The question is whether the market will find a solution and get comfortable with clearing in EU venues.”

Mairead McGuinness, European commissioner for financial stability, financial services and capital markets union, has warned that extension of equivalence “does not address our medium-term financial stability concerns. I also intend to come forward next year [2022] with measures to make EU-based CCPs more attractive to market participants.”

Regulatory crackdown

This approach is indicative of a more hardline stance from policymakers. After adopting a less robust approach during the coronavirus pandemic, in 2022 EU regulators are expected to clamp down and roll back many of the flexible cross-border arrangements that have persisted beyond Brexit. New rules in the form of the proposed Banking Package 2021 (Capital Requirements Directive VI) will accelerate divergence and require cross-border activities to be licensed, with one banker referring to it as “Brexit mark two”.

CRD VI will lead to an unravelling of many of the cross-border permissions that have survived Brexit and allowed banks to maintain more of their operations in London, traditionally the international headquarters for most big banks.

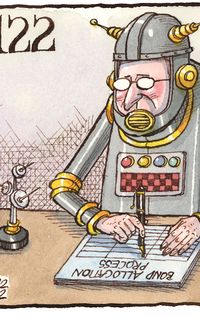

In their preparations for Brexit, banks walked a tightrope when it came to staff allocation, looking to avoid duplication of roles and infrastructure where possible while still meeting the capital and legal requirements associated with setting up branches and operations in the EU. CRD VI could prove to be a watershed moment.

“There is a constant tension to draw on talent in London and avoid doing damage to your existing business model and … duplicating headcount by having business in both places. CRD VI will tighten the screws further because it will switch off a lot of cross-border exemptions that firms have been relying on when it comes to their Brexit model,” said Peter Bevan, global head of financial regulation at Linklaters.

For example, a lot of American banks have benefited from a cross-border licence exemption that has existed in Germany but will end with CRD VI. “This harmonising requirement means national regimes will have to defer to an EU-wide requirement to bring Europe onshore. That part of the EU-facing business that has so far not been brought into the EU booking vehicle could potentially have to follow and this could be an additional significant volume of business that could be moving across, which would put further pressure on the headcount model,” said Bevan.

Global banks with established local subsidiaries in Europe are better positioned than those with a more fragmented presence. But all firms will have to adapt to CRD VI. “We still use the UK where there are permission regimes that are ongoing but there’s been a shift. For example, we started to shift our European government bond book into the Continent [during 2021] and that will continue as we ramp into the new year,” said Braden.

Fudging allocations

Banks have been able to fudge their resource allocation through chaperoning, which allows a London-based banker to advise an EU client, provided a colleague from its EU-regulated entity is present. But it’s not always an effective solution. “This creates a problem if a bank is looking to set up a new operation in a certain EU jurisdiction where they don’t have a correspondent bank because they are effectively shut out,” said one banker.

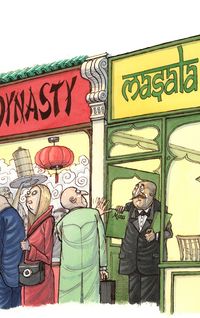

Since the 2008 financial crisis, US banks have become the dominant force in global investment banking at the expense of European firms, and their stranglehold has become ever tighter in Europe. In 2021, Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan extended their lead at the top of the European corporate finance fee tables, according to Refinitiv.

As with derivatives trading, US institutions have been relative beneficiaries of Brexit. Even so, the whole process has been painful.

“It’s difficult to see there being any obvious winners from Brexit,” said Bevan. ”It’s a bit of a zero-sum game. Brexit itself hasn’t created any additional business that didn’t exist before. It’s been more a case of sharing the business out between EU and UK venues, which means increased complexity and costs for firms. Those who have done the best are those that have been best prepared and resourced for those additional complexities.”

Brexit has created opportunities as well problems, though. “Pre-Brexit, we had our European private banking business headquartered in London and Switzerland,” said Braden. “Because of Brexit, we’ve now established Luxembourg as the EU booking location for our private bank, which has opened up opportunities for us in France and Germany.

“Also, for the first time we’re launching commercial banking in Western Europe. Because we now look at the continent in terms of how Brexit helps us, we can now invest in an array of businesses. Because we already had the infrastructure in place we’ve been able to look with fresh eyes at the opportunity.”

Longer lens

When viewed through a longer lens, Brexit will pave the way for capital markets union, because when the UK was still a member of the EU it was always pushing for greater power for member states, and with that voice removed the direction of travel is more towards centralisation.

For example, the EU is still more reliant on banks than capital markets, and that makes for a shallower pool of liquidity and a less developed ecosystem to serve its fast-growing companies. The decision in 2019 by German pharmaceutical company BioNTech, which produces a vaccine against Covid-19, to opt for a US$3.4bn listing in New York, rather than Frankfurt or Amsterdam, was more than a blow to Brussels’ pride – it showed there is still work to be done on the European project.

It’s still too early to provide a precise map of what Europe’s capital markets will look like, but it’s likely that no clear individual winner will emerge, whether a bank or a financial centre. What’s more likely is that there will be a wide distribution, with talent and resources spread across the EU, a trend that will be encouraged by the pandemic as different nationalities look to return home from London.

A shift is nonetheless underway, said Braden. “An important distinction is that banks in Europe are not only serving clients in Europe post-Brexit. They are offering European products to the world from Europe. In short, they are offering European access to the world, which is a material development.

“London will remain as the EMEA hub for a lot of financial institutions. It will continue to have its own addressable market in its own right and will continue to service the rest of the world. It’s lost in part some of the addressable market to the EU, but it’s still firing on three cylinders and it’s still got half of the fourth because Europe is still building its own infrastructure. The other three it can compete entirely fairly on,” she said.

To see the digital version of this report, please click here

To purchase printed copies or a PDF of this report, please email leonie.welss@lseg.com