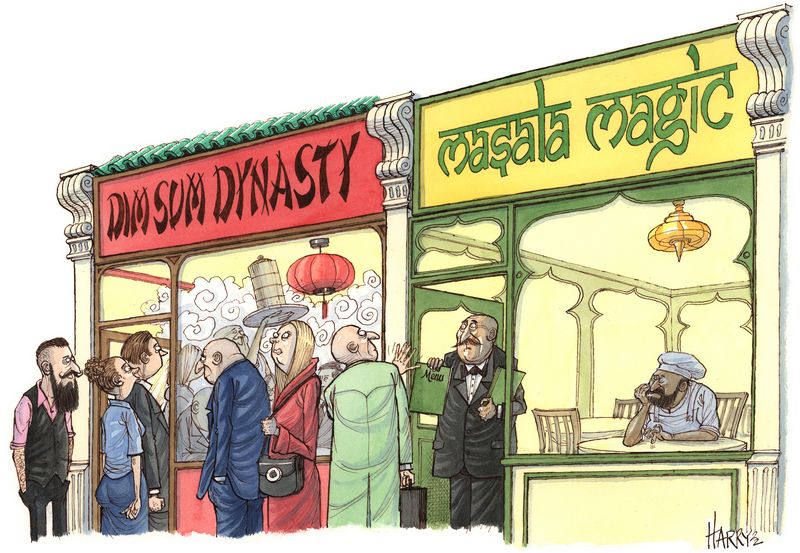

When India’s Masala bond market was launched in 2014, the hope was that it would become a vibrant issuance arena underpinned by deep secondary liquidity and a wide variety of foreign investors and traders. To say that the market has disappointed would be an understatement, but hope springs eternal and optimists are calling a turn.

![]()

The International Finance Corporation opened the Masala bond market in 2013 following severe stress in India’s capital markets as a result of concerns about the country’s budget deficit and the “taper tantrum” prompted by the US Federal Reserve’s announcement that it was reducing its quantitative easing programme.

The ensuing capital flight spurred a nosedive of the rupee and, against a backdrop of panic, the IFC and the Indian government discussed measures to deepen rupee capital markets. The Masala market was one result.

The received opinion at the time was that India had finally decided to internationalise the rupee, and that the Masala market would follow the example of China’s hugely successful Dim Sum bond market – which grew around 100-fold over a few years from its inception in 2007 as China internationalised the renminbi.

Coupons and redemption on Masala bonds are received in the settlement currency and tied to the rupee exchange rate. A US$1bn offshore bond programme was duly established in October 2013 under which the IFC would issue rupees to offshore investors – with settlement in US dollars and pegged to the rupee/dollar exchange rate – and repatriate the funds to India for investment onshore, principally in infrastructure projects.

The IFC subsequently issued Masala bonds at tenors of three, five, seven, 10 and 15 years, and the programme was increased to US$3bn in 2016.

For Masala optimists the potential of the market was demonstrated that year through two events. First, the IFC brought the first green Masala bond to support a green bond issued by Yes Bank. Then it opened the Uridashi Masala market by tapping Japan’s retail investor base with all payments settled in yen, albeit in a diminutive US$4.3m-equivalent.

That attraction also underpins complaints about the Masala market and indeed the other offshore domestic currency bond markets such as Dim Sum, and international Philippine peso bonds: that issuance represents essentially a call on the currency by the investor rather than a relative yield play.

For investors who fully hedge the rupee exposure on Masala bonds, the return is lower than could be achieved through buying the same credit in the offshore US dollar bond markets, where liquidity is higher, with the cost of forward hedging estimated to be as much as 6%.

Crimping development

“The basic fact is that non-domestic investors who are looking at getting credit exposure to India prefer to obtain that in the dollar bond market or by investing in Indian government paper for reasons of liquidity. Masala bonds have demonstrated poor liquidity and that has crimped the development of the market,” said Sameer Gupta, head of Indian DCM at Deutsche Bank in Mumbai.

As well as the IFC, the Asian Development Bank, Asia’s oldest multilateral development bank, has also been a pioneer, bringing its first Masala bond in 2014 – a Rs3bn two-year, or US$49.6m at the time – and has issued every year since with the exception of 2015 and 2018, extending its Masala curve steadily to four, five and 10 years.

“None of ADB’s Masala bonds have been swapped out. We retain all the proceeds in rupees for our local currency loans and investments,” said Jonathan Grosvenor, assistant treasurer at the ADB in Manila.

“This borrowing programme – Rs81.2bn to date – has been an enormous success story for ADB since it has catalysed important growth in our local currency lending, which results in more development assistance being delivered without currency risk.”

Such assistance will be crucial to meeting India’s vast infrastructure needs in the coming years and as India’s economy emerges from the Covid-19 onslaught. Domestic capital alone will be insufficient to fund the 500GW of non-fossil fuel capacity targeted by 2030 – from the current 100GW – touted by prime minister Narendra Modi at last year’s COP26 climate conference in Glasgow.

Regulatory constraints

But the Masala market development is constrained by regulatory requirements. As well as restrictions on issuer type and eligible investors, a crucial impediment is a pricing cap of 500bp above Indian government bonds – a constraint that effectively prevents the development of a high-yield Masala bond market.

The latter is something that is arguably required to develop India’s infrastructure, given much of the country’s energy sector sits at the lower reaches of the credit curve.

Certainly, the domestic debt market is too small to meet India’s green energy transformation ambitions, given the absence of dedicated ESG funds within India, something that has stymied green bond rupee issuance. A Rs12.4bn green rupee bond offering from units of renewable power producer Vector Green Energy was a rare standout in June last year. Before that, a modest US$27m-equivalent print from the city of Ghaziabad Nagar Nigam had been the only green offering all year.

The most common comparison of the Masala market is with the renminbi-denominated Dim Sum market, where issuance is brought and trades in Hong Kong. The Dim Sum market displays a vibrancy sorely lacking in the Masala market and the comparison relates mainly to currency dynamics, albeit that the former has been helped by the sustained appreciation of the renminbi and the latter hindered by the opposite.

At its peak in 2017 following a few years of sustained rupee appreciation the Masala market registered a relatively pallid Rs268bn (US$3.6bn) of issuance via 79 deals, according to Refinitiv data, with issuance plummeting to Rs93bn the following year and averaging just Rs53bn over the past three years.

By contrast, at its peak, Dim Sum issuance chalked up US$54.9bn-equivalent in 2014, but has steadily fallen, printing US$12bn-equivalent in 2021 as the onshore renminbi bond market expands its reach to overseas investors through Hong Kong’s Bond Connect scheme. Still, despite the reduction in issuance from the “glory days” of the Dim Sum market, there is no doubt that its critical mass can only be the envy of Masala market proponents.

Dim Sum issuers also enjoy low swap arbitrage costs. There is a 10bp–15bp saving at the moment for swapping renminbi to US dollars, explaining the recent surge of Dim Sum issuance via 136 deals in 2021 versus just 97 the year before – to complete a virtuous circle, even if the maturity profile of the market is short, averaging three years.

That is in contrast to Masalas. “Investor demand for Masala bonds can be ephemeral and since 2018 risk-off has prevailed for the Indian rupee, with occasional issuance windows opening,” said the ADB’s Grosvenor. “By comparison the Dim Sum market has been more consistent, but issuance is swap-driven so other factors are at play.

“Demand in the Dim Sum market also tends to be concentrated in short dates up to three years, whereas the Masala market extends comfortably to 10 years.”

For Masala bond market bulls, reasons for optimism exist in the bank capital arena. In the Additional Tier 1 rupee market, restrictions prevent retail investment and mutual funds from buying paper, an impediment that prompted HDFC Bank to tap overseas investors via a Rs7.4bn AT1 perp non-call five Masala in September.

The unrated trade came at 7.55% some 17bp inside State Bank of India’s AT1 rupee domestic bonds that priced earlier that month, illustrating the pricing potential of Masala paper in that space.

Grosvenor is optimistic about the Masala market’s potential to revive in 2022. “Potentially the inclusion of India in the global benchmark indices in 2022 will rekindle interest in the Masala market,” he said.

And certainly that move is significant. “On the basis of benchmark inclusion, around US$20bn–$30bn could flow into India’s bond markets in the first year, with around US$8bn–$10bn annually after that, which could lead to rupee appreciation,” said Prasana Balachander, head of global markets and proprietary trading at ICICI Bank in Mumbai.

Sovereign Masala issuance from India was also supposed to be a market reviver when mooted in 2019. However, plans to issue up to US$2bn–$3bn as long as 30 years in offshore debt failed to materialise due to foreign exchange risk concerns. A Masala would not be able to deliver the size or tenor available in the offshore US dollar market and those plans came to nothing.

Hope springs eternal nonetheless and when the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank issued a sustainability bond in the Masala format last June via a Reg S two-year – albeit a minuscule Rs2bn – the talk was of a major new player emerging. If the stars align, it may yet happen.

“AIIB has been an observer of the Masala market, but somewhat on the periphery. However, it will likely become an important local currency market where AIIB will be active, given our expectations of the pipeline. To the degree that Masala bonds could boost India’s infrastructure investment, AIIB will be a keen participant in that market,” said Darren Stipe, head of funding at the AIIB in Beijing.

To see the digital version of this report, please click here

To purchase printed copies or a PDF of this report, please email leonie.welss@lseg.com