IFR Asia: Let’s get started with an overview. Dafei, China is the biggest financing market in Asia, but what’s the size of the ESG component?

Dafei Huang: The ESG financing market has come a very long way since its launch in 2016. So far, the main focus has been on green finance and, in terms of instruments, green credit accounts for about 90% of China’s entire ESG finance landscape.

By the end of 2021, the outstanding balance of green loans had risen to more than Rmb15trn (approximately US$2trn), and green bonds outstanding were about Rmb1.1trn (US$165bn).

Last year alone, just over US$90bn-equivalent of green bonds were issued, representing a near 180% increase in issuance from the previous year.

On top of that, considering the 2030 emission peak and 2060 carbon zero goal announced by the Chinese president, last year the regulator launched new green debt instruments, such as carbon neutrality bonds and sustainability-linked bonds (SLB). Both types of instruments have found traction.

The introduction of a new variety of themed tools is a good thing for the market’s development and we expect the ESG market to grow to meet the huge investment needed to reach the carbon neutrality goal.

IFR Asia: Let’s look at India, the other huge market in the region. Harsha, how has ESG policy in India evolved in recent years?

Harsha Bangari: From a macro perspective, India has committed to achieve net zero by 2070 and, based on that estimate, this would require investment to the tune of US$10trn. It’s a huge amount.

In terms of policy, India has made noteworthy progress in strengthening the sustainable regulatory environment and has placed emphasis on all three pillars of development: economic, social and environmental.

Broadly, policies have been categorised as those for banks and financial institutions and those for corporates – there is a regulator for banks and financial institutions

The market is evolving. As early as 2007, guidance notes were issued around sustainable finance for banks and financial institutions. This was also followed by RBI’s decision to include lending to social infrastructure and small renewable energy projects within the priority sector lending targets.

It is a similar story in the corporate sector where the Ministry of Corporate Affairs published corporate responsibility and voluntary guidelines in 2009, but now requires a non-financial disclosure in annual accounts. Sustainability-related reporting requirements are now in place for the top 1,000 listed companies by market capitalisation.

The market is evolving. It started from the regulator providing guidance, moved to voluntary, and going forward it is likely to become mandatory for the corporate sector as well as financial institutions to start reporting on ESG.

IFR Asia: Daming, how do different types of ESG instruments suit different kinds of issuers and industries?

Daming Cheng: As the largest type of ESG bonds, green bonds are particularly important. A green bond plays several roles for issuers. Firstly, it provides funding for qualified investments in specified green projects such as infrastructure or clean energy. Secondly, it can provide cheaper financing – something we’ve seen this year. And thirdly, green bonds play a role as the verifiable conduit for the flow of the funds from the capital market to qualified projects.

In 2021, we have seen Rmb600bn of Green Bonds issued in the Chinese market by power companies, by steel companies, by a lot of issuers.

To achieve a sustainable development of the economy, the Chinese government has already mandated 45 government agencies to integrate sustainability development goals into specific economic tasks in the economic, social and environmental fields.

The market is starting to function. For example, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank – one of the most important multilateral development agencies, issued Rmb1.5bn of sustainability bonds in the Chinese bond market using its own framework. Many issuers from major industries, like clean energy, including wind, solar and hydropower, and the Chinese Big 5 power suppliers, have also issued this type of bond.

Even mining companies, like Shaanxi Coal and Chemical Industry, have issued SLBs, linking their energy consumption efficiency to the bond. Cement manufacturers and steel companies are also looking to use SLBs to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions.

Also, to coincide with the adoption of carbon neutrality goals, we will start to see SLBs linked to carbon neutrality being issued by the likes of state-owned enterprises (SOE).

IFR Asia: Edmund, what are you seeing in terms of issuers picking the structure that’s right for them?

Edmund Leong: There’s an increasingly wide range of ESG products for the issuer to choose.

For issuers, we advise the client to look at bonds that have specific ‘use of proceeds’, namely dedicated green and sustainability bonds. If borrowers have a specific ESG project to finance, then those instruments are the right choice. SLBs are a lot more flexible from the use of proceeds standpoint. The instrument is useful for companies linking funding costs to achieving an overall sustainability goal.

For the investor, an increasing number of products reflects the natural development of a growing market. A wider choice of instruments allows investors to better calibrate their ESG investment approach.

IFR Asia: How did Sembcorp decide which kind of ESG instrument to use?

Eugene Cheng: At Sembcorp, we set ourselves a transformation plan starting in 2021 by reshaping our strategy, focusing on transitioning our portfolio from brown to green. That entails growing our renewables portfolio significantly, from 2.5GW in 2021 to 10GW, and decarbonising our portfolio by reducing our carbon emissions intensity from 0.54 to 0.40 tonnes of carbon dioxide per megawatt hour (tCO2e/MWh) by 2025.

If we say that we are committed to decarbonisation as well as the renewables transformation strategy that underpins the very heart of our business, our financing strategy must also be aligned. As a result, we made the decision to finance our growth and transition out of ESG sources – SLBs as well as green instruments.

We use green bonds and loans for funding project costs, the equity contribution into greenfield projects or acquisitions of any portfolios of renewable businesses.

At the other end of the spectrum, we still need liquidity to support the day-to-day running of the business. In addition, when developing greenfield projects and acquisitions, we might need access to quick liquidity and, in those situations, we usually use sustainability-linked instruments. Most recently, we secured a S$1.2bn (US$869m) sustainability-linked revolving credit facility.

For sustainability-linked instruments, we have sustainability performance targets (SPT) which forms part of our strategy. If we do not meet those targets by 2025, we expect to pay a 25bp step-up in the interest rate.

We have noticed that investors look positively on our strong commitment to these targets.

IFR Asia: Harsha, India Exim has been in the ESG financing business for many years – one of the first in Asia. Can you describe your journey and explain how you decide which kind of instruments to issue?

Harsha Bangari: We’re agnostic to the type of instrument we issue; it all depends on market appetite or investor appetite. It’s also important for us to map the requirements of the investors with the assets we have. As an export credit agency, we participate in the medium to long-term borrowing market. As a result, bonds make up a large proportion of our borrowing programme.

We issued our first green bond in March 2015, and it was very well received in the market. Subsequently we have dabbled with some green private placements where we have issued India’s first socially responsible bond. Proceeds from this issue were used by the bank to fund infrastructure projects in the Mekong region. It’s an example of how we marry the requirements of investors with the end use of the funds.

Something we have done as a bank is we have tried to make our thinking more transparent. We have set up an ESG framework to issue green, social or sustainable bonds, and the framework has been confirmed as credible and impactful by a second party opinion provider. Our ESG framework is aligned with all the ICMA bond principles.

The framework covers six green categories: renewable energy, sustainable water and wastewater management, pollution prevention, clean transportation, green buildings, and energy efficiency. We also cover four social areas: access to essential services and basic infrastructure, food security and sustainable food systems, MSME financing and affordable housing. Of course in India, the Ministry of Small & Medium Enterprises (MSME) plays a big role in the economy, so we are also involved in MSME financing and financing affordable housing.

In terms of ESG instruments, we’ve found the bond markets to be most amenable, but I hope the loan markets will catch up soon.

We have also realised that having a framework in place really helps us in our negotiations and bilateral discussions with the multilateral agencies. The framework shows our commitment to sustainability financing and that strikes the right note with the multilateral world.

IFR Asia: Dafei, what are the opportunities in the China market in terms of transition financing – for companies or issuers that are not quite green yet but that want to reduce their impact?

Dafei Huang: Transition financing will be a massive market.

At the moment green finance focuses on green projects, focuses on renewable energy, low carbon transportation, green buildings, etc. However, heavy industry is not properly covered for two reasons.

One is the limitations placed on the use of proceeds for a green bond. That means carbon intensive industries have been unable to use this kind of financing to upgrade their operations.

We can’t overlook this issue.

China’s carbon intensive industry is responsible for over 80% of total carbon emissions, so decarbonising this industry is critical if China is to meet its net-zero goal. And this will require a significant amount of investment.

Taking the steel industry as an example, Climate Bonds Initiative estimates that for the industry to decarbonise in China, it requires about Rmb20trn of investment – the annual equivalent of around Rmb500bn.

Transition finance can effectively serve these industries and cover their needs. SLBs have been very good in providing some flexibility for these industries to tap into, but transition bonds will take support for the process to a whole new level.

This year the regulator launched a transition bond pilot in China. It’s extremely exciting. It covers four core elements: use of proceeds, information disclosure, third party certification and fund management. It’s a remarkable milestone, but there are still some technical gaps to fill before we see a vibrant transitional bond market take off.

At the moment, decarbonisation pathways are only being developed at the sector level and intermediate emission targets are only being set at the industry level. Most companies have not yet produced their own decarbonisation plan. There is still some understanding to be developed.

Looking ahead, companies and financial institutions need better guidance and standards to be set in terms of information disclosure. Financial institutions need better technical guidance to identify transition activity to ensure that their investments do not go to the wrong type of activity. And, given the size of the investment required and the need to attract international investors, decarbonisation pathways and targets, both at the industry level and the company level, must be Paris-aligned. This will provide international investors with the confidence they need to manage the risk of greenwashing and support the healthy development of the whole transition finance market.

IFR Asia: I’d like to ask two corporates about the benefits they found from issuing ESG transactions. Julian, what impact did you see from issuing ESG and did you attract different kinds of investors?

Julian Lee: We did. The US$4bn bonds that we issued earlier this year were divided into four tranches. We spent time to deliberate which tranche should be green before deciding that the five-year was the most suitable. That tranche performed very well. It was the most popular of all the tranches, with most of the allocation going to green investors.

The deal was launched into a tough market – the rates market had been volatile throughout the year, but we managed to get a good outcome. The timing was good, and we achieved reasonably low rates.

The green tranche was a principal factor in cementing the overall deal’s success.

If you consider carefully how to use the green tranche as part of your financing strategy, and think about how to maximise demand, then I reckon you will see a benefit across the whole financial strategy.

IFR Asia: Eugene, what benefits have you seen from issuing your sustainability-linked bond?

Eugene Cheng: For Sembcorp, the benefits are broadly in line with Julian’s experience. It broadened our investor reach. In the first tranche of green bonds we issued in June last year, we saw some less traditional names coming into the deal, including school pension funds, governmental agencies and more ESG-focused European funds.

For our SLB from October last year, we were very privileged to be supported by the International Finance Corporation, which anchored S$150m of the offering. That ultimately created confidence in the issue and drew in additional demand.

The other benefit is that we were able to issue very long tenors at competitive rates. Investors appreciated the strategies the bond was funding – building renewables and driving transition.

Issuing bonds in this format, linked to the firm’s overall strategy, allows us to lengthen the tenor of our issuance, attracts European ESG investors and ultimately reduces costs.

For example, we were delighted to see a ‘greenium’ when we issued our inaugural green bonds. The pricing advantage of these instruments was also evident when we launched our second SLB earlier this year into a tough market.

IFR Asia: Daming, are you seeing a comparable price advantage in the Chinese market?

Daming Cheng: Yes, exactly. When we were asked that question a couple of years ago, our honest answer would have been: “It’s hard to say. And at least there is no price disadvantage.”

But now we see a material advantage in financing costs for green bonds compared to regular bonds and that is thanks to the incentives provided by the Chinese financial regulators, namely the People’s Bank of China, the central bank of China.

The PBoC has encouraged Chinese financial institutions and investors to allocate more of their assets to the green sector: green assets, and in particular green bonds and loans. And with these green assets, institutions and banks enjoy extra regulatory benefits. So, because of these incentives we are seeing the investor base for green bonds grow. As a result, green bonds recently issued in the Chinese market – particularly investment grade – have been vigorously chased by investors resulting in a price advantage of somewhere between 5bp and 20bp to conventional deals.

IFR Asia: Alvin, what advantages do you see for issuers, whether it’s pricing or something else?

Alvin Yeo: Clearly pricing is one of them. Issuers are becoming increasingly smart about aligning ESG strategies at the corporate level when pursuing sustainable finance and the benefits are filtering down to transaction outcomes.

In the Airport Authority’s case, they were able to use the green tranche to the benefit of lowering the overall financing cost of what was a large transaction. And in Sembcorp’s case, they managed to bring in a very strategic investor which helped them on the deal’s ESG structure as well as helping them to secure a longer tenor for it and reduce its financing costs.

We are also seeing investors become very vocal about what structures they like. And when they do like it, they buy it, which translates into a benefit to the borrower. It helps with the overall execution.

In the secondary market, at least in the offshore US dollar bond market, there is increasing quantitative evidence to suggest that an issuer’s green bonds trade tighter than their conventional bonds. This translates into a pricing benefit in the primary market.

There are some other tangible benefits to borrowers from issuing green instruments. Some regulators, for instance, have developed schemes and subsidies as an incentive to launch green products. The Hong Kong Monetary Authority, for example, has the Green and Sustainable Finance Grant Scheme that has helped first time issuers cover some of the transaction expenses of bond issuance.

IFR Asia: Edmund, do you see any ‘buzz’ points for issuers in ESG finance?

Edmund Leong: I share the same views as Alvin and Daming, although the extent of any benefit from issuing green bonds is still going to be very dependent on prevailing market dynamics at the point of pricing. For Sembcorp, having a strategic investor like IFC will always provide pricing tension during the bookbuilding process.

There are non-financial benefits for issuers. For example, SLBs communicate targets set for internal operations to investors – how the company is improving its energy efficiency, the way it deals with waste disposal of a factory or manufacturing operation, and its performance against social issues such as employee safety.

This is important not just to investors but to all company stakeholders.

IFR Asia: You don’t get these benefits without doing a lot of work. So, Julian, how much work goes into an ESG issue? Not just at the time of issue but afterwards.

Julian Lee: Planning took almost a year, but we are fortunate to have a supportive sustainability department. The hard part is how to sync up the market need with our own corporate strategy and doing it in a dynamic manner.

We spent time to work on our framework and then the second party opinion provider, as it takes time to give their opinion. You need to do all the preparation and planning needs to be very deliberate.

But the dynamic part is when you come to market. For example, in our US$4bn deal, we initially thought the green tranche should be small – US$500m. But, by then, we were faced with increasing interest rates and volatility and, given the extent of our green assets, we decided to increase the tranche to US$1bn.

That decision helped us in raising the full US$4bn and in ensuring success with the other 10, 30 and 40-year tranches. Having a strong, well-priced five-year green bond allowed us to price through the curve out to the 40-year bond as well.

Reckoning with market dynamics, working on the corporate strategy and consulting with advisers and investors helps you decide the best way of achieving your financing target.

Yes, a lot of work goes into it. But I think the ability to issue a bond into a tough market makes all that work worthwhile.

IFR Asia: Eugene, at Sembcorp how much work went into disclosures and reporting?

Eugene Cheng: When we talk about disclosures and reporting around the issuance of green or sustainability-linked financing instruments, there isn’t much incremental work that needs doing. Once the sustainable financing framework is in place then the disclosure documentation is standard.

We have a robust sustainability report, disclosing our climate as well as social and governance performance, which is aligned with Global Reporting Initiative standards.

The game changer for us was developing a transition strategy and setting hard targets behind it. We said that by 2025, we would increase our renewables generation to 10GW from 2.5GW, reduce our carbon emissions from 0.54 tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions per megawatt hour, to 0.4 tCO2e/MWh and, by 2030, reduce Scope 1 and 2 greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions to 2.7 million tCO2e, which represents a 90% reduction from the 2020 baseline.

All these strategic targets form the sustainability performance targets in the financing frameworks and are also tied to executive compensation.

Being comfortable disclosing these targets gives investors the confidence that whatever we claim for our green and sustainability-linked instruments are underpinned by clear objectives, forms part of our remuneration and ensures that the entire organisation is focused on fulfilling the objectives that are being financed.

IFR Asia: SLB and sustainability-linked loan issuance has gone through a lot of growth in the last couple of years and they are particularly popular in Asia. But terms are far from standardised. Alvin, do you see any flavour of SLBs aligned to any mechanism that is going to be popular?

Alvin Yeo: First, we need to differentiate between an SLB and an SLL. There are some fundamental differences.

For SLBs, we should look at it from the perspective of both the investor as well as the issuer.

You need to recognise that investors are not always going to favour a structure where they get an increased return in the event the issuer does not meet its targets. This may seem counterintuitive – if investors get more from a coupon step-up, then they should be happy. But, with this product, that is not the case.

Take fund managers, for example. How would stakeholders react if a fund manager bought a bond on the basis that the issuer is committed towards meeting its targets but, at the end of the day it fails to do so? Fund managers profiting from an issuer’s poor performance does not look good. It’s one dilemma to think through.

Likewise, bank treasury investors may have issues with accounting treatment for bonds where the interest rates could fluctuate, such as in the case of the SLB if the penalty mechanism involves a coupon step-up.

From the investor’s perspective the structure also needs to make sense which means they need to understand the rationale of why the issuer is issuing in this format.

There are also differences in thinking across different type of borrowers. Some family-owned businesses want to do well in terms of sustainability; they have a strong commitment towards the alignment of the ESG targets against the financing strategies. But, at the same time, they may struggle with the position that investors would benefit financially if the firm cannot meet its ESG targets.

Satisfying these different approaches is fundamental in determining the choice of structure of a SLB. And, as such, I don’t think that there is going to be a market standard for SLBs in the near term.

At the end of the day, each structure is going to be determined by answering the key questions: why am I doing this deal? What sort of message do I want to send to investors? And what sort of investors do I want to target?

As an issuer, if I’m targeting a bank treasury desk then I need to know that the structure of any deal is right for them. I may want to consider a different format where the financial penalty goes towards, say, the purchase of carbon offsets, renewable energy credits or even funding climate change research.

Issuers need to think about these things. They need to be confident that when they go to investors, they can say: this is why I’m doing this deal, and this is why I choose this structure.

SLLs are more privately negotiated between the lender and the borrower, so there is more room to discuss the kind of considerations I’ve talked about. But, essentially, there’s more flexibility in terms of coupon step-up, coupon step-downs, and choice of target.

Edmund Leong: It’s very difficult to have a one size fits all structure for SLBs – it really depends on how investors perceive the targets. For example, when we did a deal for Nanyang Technological University, the penalty for not hitting the targets was not a coupon step-up but a one-off 50bp flat contribution into additional climate research and technologies on climate change mitigation, or to buy renewable energy certificates or certified carbon offsets.

SLLS are more customised. We can get into a bit more granularity with issuers in terms of choosing SPTs and providing incentives to borrowers should they overachieve. We have seen coupon step-downs, for instance, which effectively provide a financial incentive for the borrower to hit its targets.

IFR Asia: There’s no single global standard for ESG bonds and loans. Harsha, what kind of challenge does that create for emerging markets?

Harsha Bangari: That’s a good question, especially for India. The key challenges for ESG bonds and loans continue to be disclosure, accountability and taxonomy of green. While I agree that there’s an increasing need for harmonising sustainability standards, a one-size-fits-all approach, in my mind, cannot be adopted immediately, particularly for emerging markets.

In emerging markets, the focus is more towards transition or mitigation and is more localised. The process also depends on the country’s position along the economic development curve.

Most importantly, we need to understand that the price of some technologies makes ESG investments non-viable, particularly in emerging economies. There is a need to strengthen policy in terms of making such technology affordable. India’s progress in the solar energy space is a classic example of strengthening the overall ecosystem and reducing costs.

So, while we should have harmonisation standards, I think a little bit of flexibility would be welcome given the transition most emerging economies are going through. That would also encourage these economies to move towards the final goal of sustainability.

IFR Asia: Daming, how are Chinese standards around ESG financing developing?

Daming Cheng: I can see three features when talking about Chinese standards. First, there is increasing uniformity. In China, we have two bond markets: the exchange bond market and the interbank bond market.

In the past, we had different standards for the two markets and that presented difficulties for issuers and investors. But in 2021, the PBoC published a taxonomy that will unify green bond standards and definitions across the whole Chinese bond market.

That was a particularly important milestone for the development of the Chinese green bond market.

The second feature comes from the international connection. We are seeing stronger international flows as the Chinese capital markets open up. There is increasing interest from international investors in buying domestic Chinese bonds. Last year, they bought Rmb3trn of Chinese Government Bonds, for example.

As the Chinese domestic bond market internationalises, it is essential for us to coordinate green bond standards in China with those in the rest of the world. We are making step by step progress. For example, at the end of last year we published what we call a common ground taxonomy, which provided a link between the PBoC’s taxonomy in China with that in Europe. Finding common ground between these two taxonomies means only one certification is needed to satisfy the requirements of both Chinese and European markets.

The third feature is acknowledgement. Previously, green bond issuers and listed companies found providing ESG information disclosure an extra burden to their day-to-day business. But now more and more businesses, especially frequent issuers and sophisticated issuers in the Chinese bond market, have already established their framework for green bonds, their framework for ESG and they are ready in their day-to-day operations to disclose ESG information. The ESG concept in China has been recognised and accepted.

Dafei Huang: Finding a consensus on how ESG investing is quantifiable, credible, comparable, and verifiable is vitally important in transitioning towards greater transparency.

IFR Asia: In the onshore market in China, Dafei, I understand that there are some quite innovative instruments related to the carbon market.

Dafei Huang: Yes, that’s true. China’s national carbon market launched last year and created quite a lot of excitement. The market covers over 2,100 power generators and over 4 billion tons of CO2 emissions per year. The market is already massive and it’s only going to get bigger by 2025.

There will be an offset scheme with carbon credits supporting the generation of green projects. Carbon pricing introduces direct incentives to industries and companies to improve carbon intensity.

Companies with poor carbon performance will face either a penalty or additional carbon costs – and, eventually, challenges in accessing finance. For example, financiers and investors will start to use the carbon price to assess a company’s climate transition risk in their investment decision making.

Those companies with a good carbon performance will be able to improve their financing with surplus carbon assets and an expanded range of instruments. For example, industries are already being helped to securitise future carbon revenue and are launching carbon-backed loans. The carbon market also creates opportunities for carbon-linked bonds.

Carbon-linked bonds provide a very innovative structure, whereby the coupon consists of both a fixed rate and a floating rate based on carbon revenue. The fixed rate will be lower than conventional bonds with a similar maturity.

Buying carbon-linked bonds can also help investors support the development of green projects, so there’s a social element to the instrument as well.

This type of bond is useful for companies with eligible green assets, such as forestry, and renewable projects. Energy intensive industries may also take advantage of this structure by using their surplus carbon allowance to finance transition plans.

IFR Asia: Julian, what kind of questions are investors asking about ESG? Whether related to a particular bond issue or about the company in general.

Julian Lee: Investors are most interested in your strategy and model. They expect certain standards to be followed but there will be some grey areas, such as to what extent your business can influence Scope 3 emissions. We found that having non-deal roadshows with influential ESG investors was helpful. It’s also important to have dialogue with the ESG community, the agencies and other participants.

Dialogue with the community and investors is important because they will be able to tell you what they need, tell you the direction you should take, and they will understand some of the subtleties. Ongoing discussion and making that extra effort to communicate is key.

IFR Asia: Eugene, what kind of questions are investors asking Sembcorp? We should mention that Temasek is a significant shareholder and they’ve got their own approach to sustainability, so how does that influence Sembcorp?

Eugene Cheng: Disclosure is getting increasingly technical, with GRI (Global Reporting Initiative), SASB (Sustainability Accounting Standards Board), TCFD (Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures), etc. That poses a lot of challenges for issuers because we have to navigate these new challenges. I’m not sure if the broader investor community find all of this information useful. One question that I always pose to investors is: how do you use the information that has been demanded of us?

From an investor’s point of view – and we’re talking about the full set of investors: portfolio managers, investment analysts, bond funds and equity funds, they want to know how we hope to achieve our targets.

Being able to articulate how we plan to execute against targets is important. This means giving our investors clarity on the markets we will be focused on, how we intend to secure the project, greenfield sites, and any activities, partnerships, as well as how we plan to fund them.

Publishing decarbonisation targets is one thing but producing clear transition plans and commitments on how to achieve them is another. Investors want to see that there is also a clear strategy on how we’re going to execute.

The point is that the dynamic within investors has changed dramatically over the past couple of years.

Internal ESG departments in many funds have grown substantially to the extent where portfolio managers can no longer justify what looks like an economically viable investment through a checklist approach. So, very often, investor meetings involve both the portfolio managers and ESG departments to discuss external contemporaneous environmental, social and government issues.

Investors demand clarity in terms of being able to execute against the strategy and targets we have published. They want to see us being able to live up to what we say and to demonstrate our progress.

Temasek has a clear focus on sustainability. They have set a net zero target to achieve by 2050 and pledged to halve their entire portfolio’s greenhouse gas emissions relative to 2010 baselines. Their ambitious sustainability targets and endeavours have inspired us to be aligned with them.

IFR Asia: Harsha, what kind of questions are investors asking about ESG, both through India Exim’s status as an issuer and in the way that it employs its proceeds?

Harsha Bangari: Being a financial institution, our issuing structures are typically linked to use of proceeds.

During most of our investor engagement exercises most questions are around disclosures – the more disclosure requirements we meet, the more comfortable they are.

As regards use of proceeds, again, the discussions revolve around how, as an institution, we are factoring in accountability to the end use of the proceeds from this type of bond issuance.

Investor engagement has prompted the decision for us to set up our ESG framework and get it reviewed by a second party. We will have an ESG framework that is confirmed by Sustainalytics as being ‘credible and impactful’ and is aligned with sustainability bond guidelines, green bond principles, and social bond principles for bonds and green loan principles and social loan principles for loans.

This document then becomes the basis for an institution’s commitment to an ESG compliant strategy. Having the framework makes our discussions with investors easier. Over time, we will become much better in communicating how are we going to realise our ambitions, the level of our commitment and what type of assets we are developing.

We are like a policy bank for the government of India, and we are engaged in providing finance for infrastructure and social projects outside of India. So, again, lots of questions on how we monitor projects or how we get foreign governments, which are sovereigns in themselves, to align to the whole framework in which Exim Bank believes.

IFR Asia: Not all deals we see in Asia are going to meet the high standards of the issuers we’ve got here today. So, Edmund, what are the risks that some companies could use the ESG label for greenwashing?

Edmund Leong: It’s an increasing risk for banks. It’s mitigated with enhanced diligence in terms of client selection, ensuring that issuers adhere to having done their own due diligence, and making sure there is adequate reporting, disclosure and compliance with use of proceeds – or any other structure they have chosen. That is extremely important.

The key is for issuers to work with good ESG advisers and good bankers who essentially set up targets that are achievable yet challenging. That ensures they have a concrete roadmap towards reaching their sustainability targets.

Issuers will soon realise that failure to use proceeds correctly, or if they breach targets, that doing so would have implications for future market access. That may not just affect them from a debt perspective but would negatively impact relationships with equity investors and bank lenders. It would impact the entire capital structure.

From a UOB standpoint, apart from seeking approvals from underwriting committee for our transactions, we also have an ESG committee that will ensure the issuer adheres to the promised standards. Enhanced diligence should hopefully reduce the risk of greenwashing.

Alvin Yeo: I fully agree with Edmund from the perspective of banks underwriting a bond or loan.

Looking at it from the lens of an issuer, you could break down the risk of greenwashing into quite a few segments. First, an issuer needs to be aware of the most material ESG risks that relate to their sector, the risks specific to a particular company’s profile and its position in the industry.

The second part is environmental controversies. These may be out of an issuer’s control, but sometimes they happen. It doesn’t always mean that the company is responsible for the controversy or that it is not living up to its commitments, but it then becomes a question of how the company deals with it. How did they mitigate the consequences of the event and how do they put systems in place to ensure it does not happen in the future?

Investors understand that sometimes something bad can happen, but they will want to see how the company moves on. That speaks a lot about the management team.

The last point is about perception. Perception has more to do with when you embark on sustainable finance transactions. Investors and market participants form views on the management’s intention for doing this deal, and whether it is aligned with the issuer’s ESG strategy and philosophy at the corporate level – this is really the bedrock of what we have been discussing so far.

The choice of green, social, or sustainability-linked is all about how issuers think about the rationale behind the issuance and how investors connect this with the strategy. It all has to make sense.

Julian has articulated why he took such a long time to figure out the best way to do his deal and Eugene also talked a lot about the efforts to structure the deal from a ESG perspective to align with the expectations of the strategic investor. All of this goes back to why are we doing this and whether the market thinks it makes sense.

As bankers, interacting with management is most important, because it’s the commitment of management to do what they commit to that is key to safeguarding against greenwashing.

IFR Asia: Are there any countries or industry sectors that are expected to be big borrowers in ESG formats this year? Daming, what are you seeing in China?

Daming Cheng: Due to the Chinese carbon neutrality goal we expect a huge amount of issuance to 2060. We estimate that the green investment required is up to around Rmb130trn. That’s a massive investment.

Last year, some Rmb1.5trn was invested in clean energy and in carbon emission reductions. The electricity power sector invested up to Rmb1trn for instance across energy storage, grid improvement and clean power generation.

In 2022, even more investment will be made and based on our estimation, the total amount of clean green investment will rise to Rmb1.8trn.

ESG financing instruments will play a very important role along the way.

IFR Asia: Alvin, what do you see as the pipeline for ESG instruments this year?

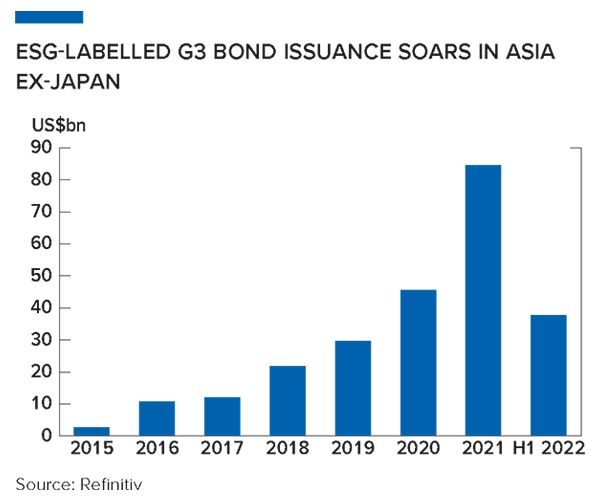

Alvin Yeo: So far in 2022, we have seen roughly US$30bn of issuance in the offshore international bond markets across green, social, sustainability and sustainability-linked bonds. About 60% of this issuance is coming from Greater China. A lot of it is from the Chinese banks. Another interesting trend is the local government financing vehicles in China. They are very active in the offshore bond market, issuing green bonds in recent weeks as well.

If you try to extrapolate this trend, basically the Chinese banks plus local government financing vehicles, you come to the conclusion that this is really a reflection of the 2060 policy push in China where China is looking for carbon emissions to peak in 2030 and then for the country to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060.

Elsewhere in the region, you also see banks and corporates from South Korea being quite active. They have issued north of US$6bn so far and it’s a good mix between corporates as well as financial institutions.

For the rest of the year, I would put money on renewable energy companies appearing in the market. There’s a similar theme as to that outlined by Daming, but they may emerge from South-East Asia as well as, potentially, India.

We could probably do with market conditions improving a bit, but Asian sovereign borrowers will remain very active for the rest of the year as they continue to push sustainable finance, setting benchmarks for borrowers in their countries.

The domestic local currency bond markets are also super active for ESG-labelled issuance.

We will continue to see a lot of deals from different issuers across the credit spectrum.

IFR Asia: Edmund, what are the key factors influencing the ‘greenium’ of a bond?’

Edmund Leong: It is very much market-driven in terms of the level of demand on the day of pricing itself and on market sentiment, to be honest. The other aspect is scarcity of supply.

For example, if a well-respected issuer launches an inaugural deal, then, by definition, the scarcity of supply in its ESG paper would affect the size of its greenium.

Another aspect is size. If the issuer is disciplined enough to set a benchmark rather than go for maximum size, then it could affect pricing tension to its own benefit.

IFR Asia: Harsha, how is India going to get to the net zero target by 2070? Are there any strategies or policies that will help India get there?

Harsha Bangari: I will not speak on behalf of the Government of India but as I mentioned earlier, the country has committed to achieve net zero by 2070 and requires US$10trn of investment to realise it.

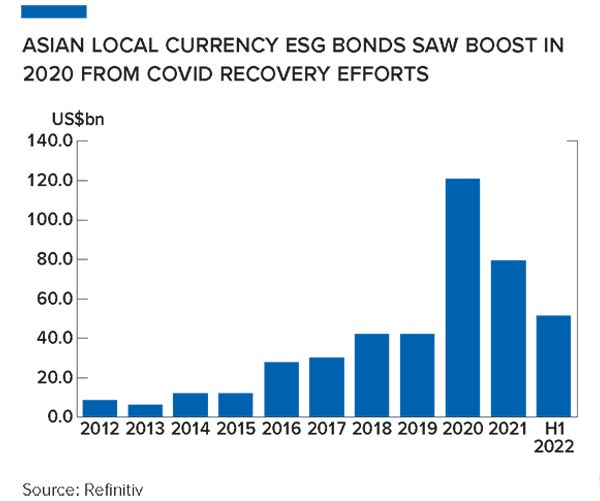

We have seen a massive surge in ESG issuance over the last two years – around US$1.3bn in 2020 to US$9.4bn in 2021.

The budget speech of 2022/23 states that India would soon begin issuing sovereign green bonds for funding public infrastructure projects in order to decarbonise the economy. The potential for a green bond issuance does underline the intent of the government in this direction. Issuing an Indian sovereign green bond could also catalyse more Indian corporate green issuances, adding to the pool of global green bond investments. In any case, any deal will be subject to favourable market conditions, and they are not that favourable now.

For the net zero target of 2070, there are targets in place to track progress. The intent is there, and we are taking all necessary steps in that direction.

The webcast is free to view, on-demand. Access it here.

To see the digital version of this roundtable, please click here

To purchase printed copies or a PDF of this report, please email gloria.balbastro@lseg.com