The credit default swap market is approaching its sternest test in over a decade as it looks to settle Russia CDS contracts, an event that could be pivotal both for securing the reputation of these controversial instruments as well as for mitigating bank losses stemming from Russia's invasion of Ukraine.

Russian CDS was ruled to have triggered over two months ago after Moscow failed to make some small interest payments on its external debt. Since then, the group of banks and investors charged with setting the terms of an auction to calculate CDS payouts have been making painstaking preparations – including lobbying the US Treasury to secure an unprecedented sanctions waiver – to ensure this potentially fraught process proceeds without a hitch.

CDS users know a botched outcome would undermine the value of these contracts as an effective hedge, something that has been repeatedly called into question since Greece’s debt default over a decade ago. But there is a more immediate concern for some of the investment banks that have used CDS to hedge Russia-related exposures this year: the fact that there are still material amounts of money resting on the result of the auction.

Market insiders say the likes of Barclays, Citigroup, Deutsche Bank, Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan have made significant sums from trading Russia CDS this year. All five banks declined to comment.

Trading Russian CDS and bonds has been one way for banks to generate significant revenues in this otherwise challenging space. The top global banks made over US$1bn trading sovereign CDS in Central and Eastern Europe, the Middle East and Africa in the first half of the year, according to data provider Vali Analytics, with most of those revenues coming from Russia and Ukraine exposure.

It is not clear how many are relying on a chunky payout from the CDS auction to crystallise some of those gains, but some have indicated they are awaiting the results.

“We wait to see the settlement process [for the CDS auction] and if the bonds can be delivered into settlement for CDS,” James von Moltke, Deutsche's chief financial officer, said last month in response to a question from IFR about how much money the bank stood to lose from its Russia exposure. Insiders estimate Deutsche has made about US$50m from trading Russia CDS this year.

Banks have been wrestling with how to slash their exposure to Russia since a wave of international sanctions in the aftermath of the Ukraine invasion effectively made it impossible to continue doing business in the country.

Societe Generale was one of those most exposed, through its Russian subsidiary Rosbank. At the end of 2021 it had total exposures of €18.6bn but these have been substantially reduced to €2.6bn at the end of June after it agreed in April to sell the entity to Interros Capital, the investment vehicle of Norilsk Nickel chairman Vladimir Potanin.

UniCredit has been unable to sell its own Russian banking unit and said last month it could lose €5.4bn in an “extreme” situation. At the end of June it held €1.3bn of Russian sovereign debt.

SG declined to say if it had made use of CDS to hedge its exposure. UniCredit didn't respond to a request for comment.

Trading gains

In reality, banks will trade CDS across different parts of their operations, making it hard to nail down their exact revenues. As well as the trading desk focused on brokering client trades, various risk managers will use CDS to hedge loan books and counterparty exposure. Sources say some banks have racked up many of their Russia CDS gains from so-called management book hedges, overarching positions that senior traders place to insulate the broader business against certain risks.

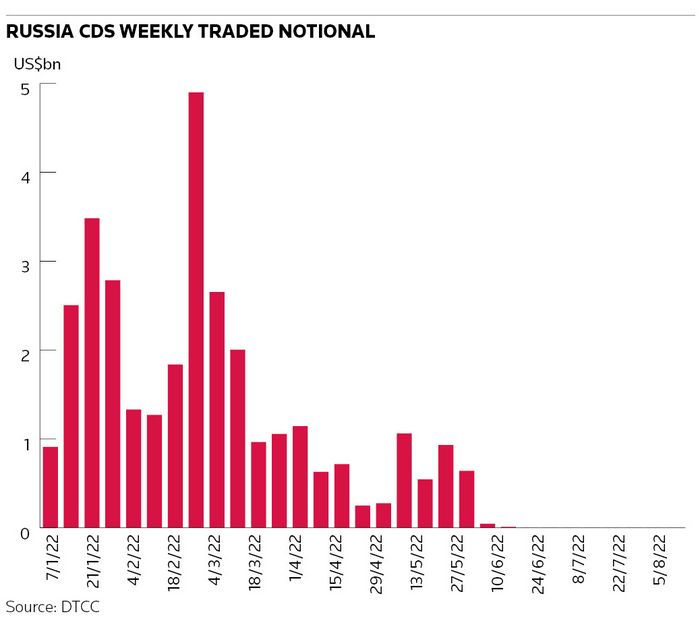

There is still over US$1.5bn of net Russia CDS exposure across the market to be settled, according to the DTCC, down from US$4.6bn at the start of the year. It’s hard to know how many banks have closed out CDS positions and locked in hedging gains. For those that still hold CDS, though, a robust auction process is vital to ensure they get paid the money they’re owed.

“In general I think [banks] are keeping their CDS positions because they think the process will work,” one industry expert said.

No guarantee

There have, however, been concerns from the outset that CDS payouts could leave protection holders out of pocket because of the complexity of the international sanctions levied against Moscow. That would benefit funds such as Pimco, which has been one of the largest sellers of CDS protection on Russia.

The credit derivatives determinations committee, a group of banks and investors that rules on CDS matters, has met about 30 times since early March to discuss Russia CDS in one sign of the unusually high level of scrutiny and caution surrounding the process.

In more recent weeks, attention has focused on the US Treasury’s decision in June to ban US firms from buying Russian securities in secondary markets. That move threatened to sabotage the auction mechanism, which requires bank trading desks to be able to buy and sell Russian debt to establish a fair pay out for CDS holders.

The committee played for time, delaying a decision on whether an auction could be held while it lobbied the Treasury to provide relief. That arrived in late July, when the Treasury's Office of Foreign Assets Control said it would allow temporary trading in Russian sovereign debt two business days prior to an auction and eight business days afterwards for the purposes of settling CDS contracts.

“In principle the auction should work now that physical delivery of the bonds is possible,” said Athanassios Diplas, a CDS market veteran who helped design the auction process.

The committee has yet to announce an auction date, but it recently published a list of bonds that could be used in the process, which is usually a forerunner to the main event. The committee’s next meeting to discuss the issue is August 15.

Despite the waiver, Diplas said there was still no guarantee the auction would function properly. That is because of the limited window for people to trade Russian bonds, which may deter some from getting involved altogether and so skew the final payout amount.

"The conditions around the sanctions make sense but they might still affect some people’s appetite to participate. If someone buys bonds in the auction, they only have eight days to offload them again if they want to. The fact that there is a cut-off will alter behaviour,” he said.

Officials at one bank which would usually be an active participant in CDS auctions told IFR they had not yet decided if they would take part in this one.