Market participants urge greater transparency and hope for supportive Chinese policies

Investors in Asia’s high-yield bond market have been forced to adapt during a turbulent year, in which defaults by Chinese property developers roiled markets and primary issuance volume plunged.

For investors to regain confidence in the sector, issuers need to be more transparent and government policies related to China’s housing market need to be loosened further, said participants in IFR Asia’s High Yield Roundtable, held via webinar on September 14.

Bad news from China’s property sector, which represented a huge chunk of Asia’s high-yield issuance in past years, has been coming thick and fast at investors in the last 12 months. This has been compounded by poor market conditions due to rising rates and geopolitical turmoil, leading to a general risk-off attitude.

“Where we are today is very much the result of a lack of confidence. In Chinese property, as much as we see a buyers’ boycott in physical markets, we have a boycott by the investors of high-yield bonds and hence you see dollar capital markets have been closed to new issuance,” said Monica Hsiao, founder and chief Investment officer at Triada Capital, a Hong Kong-based asset manager.

The crisis in China’s property sector has effectively muted primary market activity. Developers have been under growing pressure from the authorities to deleverage, leading to many failed projects and unpaid debts. Some home buyers have stopped paying mortgages for unfinished projects, and the once strong demand for housing shrank thanks to strict zero-Covid policies.

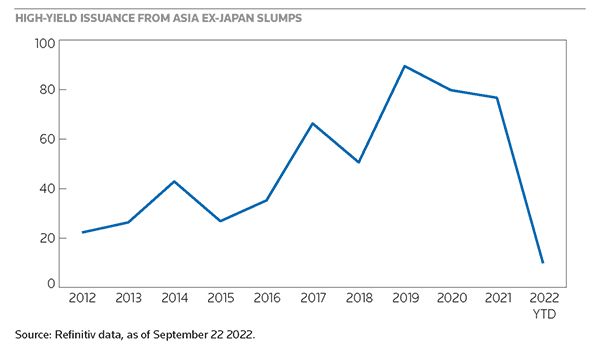

Most US dollar high-yield bond issuance in Asia used to come from the Chinese property sector, and volumes have plunged since the industry’s troubles began. High-yield US dollar bond volume in APAC reached about US$10bn as of September 22, a 85% drop compared to the same period in 2021.

Investors are now grappling with restructurings and exchange offers for outstanding bonds, as they also seek safer pastures.

“The business model for a lot of these Chinese property companies changed quickly, and the firms’ ability to adapt is quite limited within that time frame, so it’s difficult to project how the recovery scenarios would pan out for the sector,“ said Edward Tsui, head of APAC debt syndicate and North Asia DCM at Deutsche Bank.

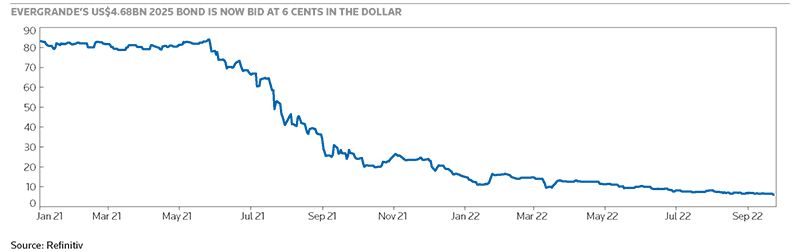

Developers including China Fortune Land Development and China Evergrande Group defaulted on US dollar bonds in 2021, with even more companies following in 2022. Some investors have pushed back on the proposed restructuring terms, citing the firms’ unwillingness to cooperate and a lack of information.

“It’s hard to analyse credit quality when you’ve got a company that has cash on balance sheet and has said it will use it to repay debt, and yet then chooses to do other things,” said Annalisa Di Chiara, senior vice president for corporate finance at Moody’s.

Hsiao said the lack of confidence is due in part to corporate governance issues, both perceived and real.

“The overarching challenges for us on the buyside are: a. How do you do financial analysis when the public information is unreliable, incomplete or misrepresentative? and b. Here in Asia, after a default, we have lots of situations where financial advisers and the issuers themselves are not forthcoming, not very open in presenting information, and therefore not enabling the bondholders’ committees to truly work with them in a commercial manner.”

Investors looking for a reprieve will be keeping an eye on government policies.

China has adopted a series of measures to stabilise the market. Those include a rate cut, a reduction in loan prime rates, guarantees from state-owned China Bond Insurance for onshore bond issuance from certain developers, and special loans from banks for real estate projects, said Derek To, executive director in the FICC department at China International Capital Corporation, adding that some cities also lowered restrictions on home buying. “It might take some time, but all in all I believe we are headed towards the right direction,” he said.

But the government still needs to do much more. S&P estimates that China would have to provide at least Rmb700bn (US$149bn) to Rmb2trn in a downside scenario to help developers finish projects, which far exceeds a special fund of around Rmb200bn the government plans to set up to tackle the issue.

The other policy factor will be any softening of zero-Covid after the Chinese Communist Party congress to be held in October.

“If there’s no fundamental improvement in the Covid lockdown situation in China, the problems should further escalate – most of the pain has been delayed and extended into 2023, so not much haircut has been taken. If nothing material improves in 2023, we may start seeing investors take more drastic measures,” said Edric Tan, head of Asia debt syndicate at Standard Chartered Bank.

Still, investors may find high-yield opportunities in other parts of the region. Bankers say one high-yield borrower from outside China is eyeing a primary market sale soon.

“Investors are seeing opportunities in, for instance, Indonesian commodity credits which are faring well. Indonesia’s commercial real estate is recovering, and there are no major refinancing walls that are upcoming in the year,” said Tan.

(The webcast is free to view, on-demand. Access it here)