A jumbo countdown timer has been sitting on Tom Wipf’s desk in Morgan Stanley’s New York office for the past four years, ticking down the seconds until midnight on June 30. That is the moment when the last vestiges of US dollar Libor will disappear, ending a decade-long saga to strip the controversial bank lending rate from about US$220trn of financial contracts.

There’s a palpable sense of relief for those, like Wipf, heavily involved in a transition without precedent in modern finance for its scale and complexity. But there’s also trepidation in corners of markets still scrambling to adjust to life after Libor.

“We believe people have everything they need to successfully navigate this,” said Wipf, a vice-chair at Morgan Stanley and chair of the Federal Reserve's Alternative Reference Rates Committee, a private sector group convened to aid US dollar Libor transition.

“But this is an enormous undertaking, so there are going to be some [unexpected] things we’ll see.”

The bank loan market sits at the top of the list of concerns heading into the end of the month. Libor-linked loans still account for about 55% of holdings in collateralised loan obligations, Barclays said in early June, although there has been a flurry of deal switching activity in recent weeks ahead of the month-end deadline.

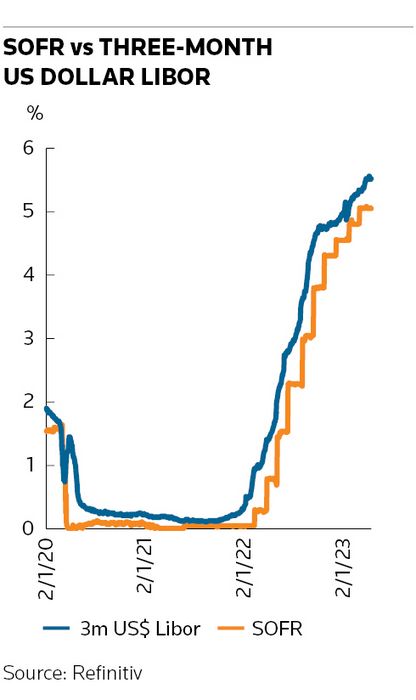

Regional US banks have been particularly reluctant to drop Libor in favour of regulators’ preferred replacement: the secured overnight financing rate, or SOFR, based on Treasury repo trades. They say rates like Libor suit their lending activities, regardless of the flaws that ultimately led to the benchmark’s downfall, and believe SOFR to be a poor substitute.

Regulators have made some concessions to those concerns, allowing the use of term SOFR – longer-dated versions of the overnight rate that better match the economics of commercial loans. But they haven’t budged from their central mission: hardwiring what they feel is the most robust interest rate into trillions of dollars of financial products.

“We chose the repo market because it has held up for decades [including] through the financial crisis,” said David Bowman, senior associate director at the US Federal Reserve Board of Governors, at ISDA’s annual general meeting in May. “It’s the most resilient market we have.”

Fix or replace

The Fed and the Bank of England started paying greater attention to Libor after it became clear during the 2008 financial crisis that some banks were fabricating the borrowing rates they submit daily that are used to calculate the benchmark. Funding markets had seized up, forcing banks to guess where they could borrow. Many put in low-ball rates to avoid looking weak – some with encouragement from the UK official sector.

Subsequent revelations that some bank traders had rigged Libor to juice their own profits intensified that scrutiny. Regulators soon gathered under the auspices of the Financial Stability Board to uproot the series of interest rates that had become deeply embedded in the global financial system over previous decades – albeit more by accident than design.

Some took a different view. The European Union decided to reform rather than eradicate Euribor, which underpins about US$150trn of financial contracts, and Hong Kong stuck with Hibor. But most global and national regulators concluded that Libor wasn't sufficiently robust to avoid the risk of manipulation, while other benchmarks they examined also proved painfully short on underlying trades.

Overnight loans proved to be the exception. Trades were plentiful – a daily average of US$1.3trn this year in the Treasury repo markets underpinning SOFR – and the new benchmark rates looked suitably sturdy. But forcing new financial products like bonds and derivatives to adopt these rates was one thing. The next challenge was developing fallbacks to deal with the vast amount of Libor-linked legacy trades.

Derivatives markets accounted for the lion’s share of these, and trade body ISDA was tasked with developing a legal pathway to convert these transactions automatically if necessary. More than 16,000 firms – and more than 90% of the derivatives market by some calculations – agreed to ISDA’s fallback protocol, which became the template for other markets, including bonds and loans.

“Regulators focused on the use of alternative rates in new transactions, but also needed to address the hundreds of trillions of existing Libor derivatives and other products that were going to be outstanding for a long time without a workable fallback," said Ann Battle, senior counsel, market transitions, at ISDA.

"The new fallbacks were the mechanism to prevent that legacy stock from causing a huge systemic disruption."

Lagging behind

With fallbacks in place, countries such as the UK, Japan and Switzerland forged ahead with erasing Libor from their markets. All had disappeared by the end of 2021 but progress was more sluggish in the US where the largest rump of around US$200trn in Libor products remained. Regional lenders still clamoured for a Libor lookalike: a term rate that reflected bank borrowing costs so they could match their assets (in this case, commercial loans) with their liabilities (funding costs).

Fearing a rerun of the crisis that led them here in the first place, regulators poured cold water on industry plans to develop “credit-sensitive” Libor replacements. Instead, they advocated limited use of term SOFR – a series of short-dated lending rates based on futures contracts traded at exchange group CME that were designed to ease calculation challenges for commercial loans.

“The concern about term SOFR was people would promote it to be the main benchmark instead of using overnight SOFR, hollowing out the market you needed to create term SOFR,” the Fed’s Bowman told IFR. “With CME embedding ARRC recommendations into the licence agreement, we have a long-lasting solution to that.”

With the mid-2023 end-date looming, regulators jump-started the transition to SOFR in derivatives markets with a series of initiatives to foster trading in contracts linked to the rate. Progress accelerated this year as the Libor deadline neared. Clearinghouse LCH (which, like IFR, is owned by London Stock Exchange Group) converted US$45trn of derivatives to SOFR in April and May in one important milestone.

By this time SOFR accounted for more than 85% of daily volumes of interest rate risk in the linear swap market, the ARRC said in April. Meanwhile SOFR was being used in more than 95% of new floating-rate note issuance and most agency adjustable mortgages.

“A number of clients weren’t as far along with their preparations as we would have hoped at the start of the year, but that has changed meaningfully in the last three to four months,” said Gregg Geffen, JP Morgan's head of North America corporate interest rate derivatives. “Now, the overwhelming majority of clients have either already transitioned their portfolios or have a plan in place."

Home straight

The loan market has undoubtedly been the laggard heading into the final straight. But even there things have picked up. Geffen said JP Morgan had done a number of term SOFR trades with high-yield companies to transition Libor-linked loans and derivative hedges.

Bankers expect more switching activity in the coming months as the first loan payments are made following the June 30 deadline. That’s because loans contracts won’t need to move to a new rate until the current interest rate contract is finished, said Meredith Coffey, executive vice-president at the Loan Syndications and Trading Association. That means a three-month Libor contract locked in on, say, June 15 will still pay Libor until September 15, allowing additional time to move to the fallback rate, she said.

There are other safety nets in place for knottier financial contracts ahead of June 30 including the Libor Act, passed by Congress in 2022 to deal with instruments proving hard to transition.

But now, with the heavy lifting behind them, regulators and industry experts strike a confident tone as Libor’s drop-dead date draws near.

“The biggest challenge was inertia to the status quo,” said Morgan Stanley's Wipf. “Even with Libor having been exposed to have the fault lines it had, it was still difficult to get to that critical mass point in this transition.

“We’re now approaching the end-date with the potential for economic consequences. That should be the remaining incentive for people to get this done,” he said.

Additional reporting by Kristen Haunss