Banks’ trading units have a major personnel issue: hedge funds keep hiring their best staff.

For all the talk of algorithms and artificial intelligence, talent remains investment banks’ most precious commodity. After all, it is still people that make the risk management decisions that often determine their fate.

Unfortunately for banks, the war for talent has never been fiercer, whether that’s for traders, quants or tech specialists. The twist this time is banks’ main competition is coming from their fastest-growing customers. Large hedge funds are on a hiring spree – and it shows no sign of abating.

“The competition for talent, especially the best talent, remains very, very strong,” Goldman Sachs chief executive David Solomon said on its third-quarter earnings call on Tuesday after the bank reported that compensation expenses had increased to the highest level for years as a percentage of revenue.

The hedge fund industry has plateaued in recent years, but underneath the headline numbers there has been an extraordinary expansion in large, multi-strategy and fixed-income funds. Multi-strategy funds, which make bets across different asset classes, have swelled to US$600bn to account for about 20% of industry assets under management, according to Goldman Sachs.

That is significant because these firms employ huge numbers of traders, making them much bigger poachers of bank talent than the equity long-short hedge funds that have dominated the industry. That is particularly true of multi-manager funds, a subset of the multi-strategy firms that operate lots of individual “pods” (or small groups of traders) to make their investments.

Multi-manager funds account for 25% of headcount in the industry despite only representing about 10% (US$311bn) of its AUM, Goldman says. Headcount has tripled at these funds over the past eight years, comfortably outpacing their growth in assets when staffing levels have been stable in other parts of the industry.

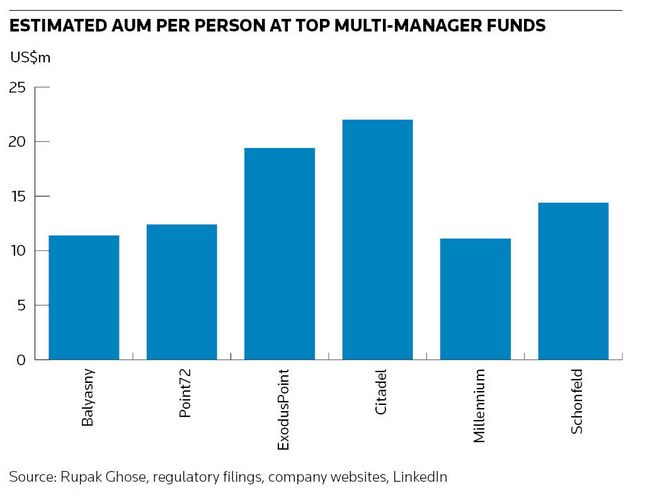

SAC Capital was one of the pioneers of this trader-centric business model, with a headcount of almost 1,200 and AUM of US$17bn at its height in 2007. That equated to AUM per employee of around US$14.2m.

SAC Capital was forced to close following a US regulatory investigation. But fast forward to the present day and the largest multi-manager funds – including Point72, the latest venture of SAC Capital owner Steve Cohen – have an AUM-to-employee ratio about five times lower than the rest of the industry, underlining just how people-heavy they are.

There are several reasons for this seemingly inexhaustible hunger for trading talent. Multi-strategy firms and most large, fixed-income funds focus more on short-term trading than long-term investing, meaning bank traders with strong risk management skills are in high demand. And while the top firms may still prefer to hire portfolio managers with strong track records from other hedge funds, these PMs still need big trading teams to support them.

It appears these trading teams are already starting to rival investment banks’ own operations in terms of scale. The six largest multi-manager funds have more than 14,000 staff between them, according to regulatory filings and other public data, around half of which will sit on investment teams. Millennium Management, one of the most successful firms in recent years, is by far the largest with 5,400 employees.

The top 12 banks have just over 30,000 sales and trading staff, according to analytics provider Coalition Greenwich. That implies an average of 1,250 traders per bank, assuming an equal split between sales and trading – only a little more than the average at the largest multi-manager funds.

So how are multi-manager funds able to sustain such large cost bases? Rather than demand the traditional management and performance fee (the old 2% and 20%), these firms “pass through” all the running costs of their teams to clients, while still claiming a chunky share of the fund’s profits. That has effectively given firms carte blanche to staff up. It also means they can afford to pay better wages than the bank trading desks they raid.

Some clients may begin to baulk at the costs, particularly in a world of higher interest rates, and if investment performance falters. But there are still reasons to believe banks’ talent problems will persist.

For one, there’s a limit to how much external capital can be yanked from firms like Point72, where a large percentage of AUM comes from the founder and senior staff. There’s also the fact that top firms like Citadel and Millennium Management have been closed to new money and increased their proportion of locked-in long-term client funds, which should allow them to grow AUM if required. Then there’s the prospect of new fund launches sucking away more talent, such as former Millennium co-CIO Bobby Jain’s Jain Capital. Finally, bank budgets will remain tight amid growing regulatory costs.

Former bank executives are now well ensconced within the higher echelons of many of these firms. Goldman’s former co-head of securities Pablo Salame is co-chief investment officer at Citadel, while Paul Russo, another Goldman veteran, is co-CIO at Millennium. It may suit some banks to maintain a close relationship with these powerful clients. But it also shows their staff the career opportunities on the other side of the fence – especially given the tendency for ex-bankers to go back to their old firms to hire people they know are good.

Bank executives need to outline a compelling narrative for their best traders to stay put – and fast. PM churn is often high at the large hedge funds due to their sink-or-swim mentality. Nowhere is this more prevalent than at multi-manager firms, where a 10% drawdown can lead to the whole team getting fired.

Sitting in the middle of client flows confers considerable advantages to bank traders when it comes to turning a profit. Working on a bank trading desk may have become more boring in a world of tougher regulations – and worse paid. But it probably offers better job security than the even more cut-throat world of hedge funds.

Rupak Ghose is a former financials research analyst