OPINION – Is the sellside ready for an end to the hedge fund bonanza?

Investment banks are more dependent than ever on hedge funds for revenues. But what if we have hit peak hedge fund business?

Hedge fund underperformance has created a certain degree of Schadenfreude for industry watchers. The HFR index of hedge funds was up a mere 6% in 2023, dramatically behind most stock markets.

Hedge fund returns have in fact lagged for the past decade, with poor industry inflows, and this hasn’t stopped them from being a growing client base for investment banks. This is especially true given the recent deal drought and the perennial pressure on traditional active fund manager clients.

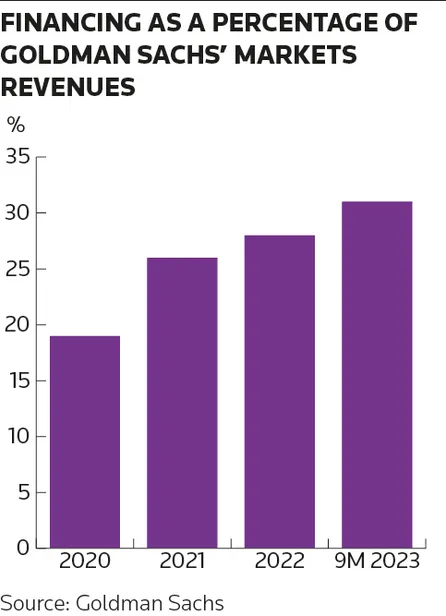

Prime brokerage revenues at investment banks have doubled over the past decade to around US$30bn. This is still only 15% of markets revenues but disproportionately skewed to certain players. Market leader Goldman Sachs has seen its financing revenues (mostly, but not all of it hedge funds) almost triple over the past decade. In the first nine months of 2023, this was more than 30% of its markets revenues. For Morgan Stanley this was 28% for the same period.

There are smaller prime brokerage franchises that are also increasingly reliant on this revenue source. Barclays' markets financing revenues in the first nine months of 2023 were less than half of Goldman’s but 38% of its overall markets revenues.

Even firms that are traditionally less exposed to hedge funds, such as Bank of America, are seeing financing increasing in importance for their markets businesses.

Hedge funds are also a very large client base on the trading side of the business, especially for those banks with strong prime brokerage franchises.

The key to the growth of the hedge fund wallet for the sell-side was not industry assets under management but the rapid growth of regularly trading, highly leveraged multi-strategy firms, especially “pod shops”, a subset of multi-strategy firms that operate lots of individual “pods” – or small groups of traders – to make their investments.

Pod shops have marginally outperformed the rest of the industry over the past five years and crucially done well in down markets. But returns are highly concentrated around Citadel, and, to a much lesser extent, Millennium. Fast-growing pod shops such as Balyasny and Schonfeld struggled in 2023. Other large multi-strategy firms like Brevan Howard also had weak returns.

Unlike top-tier private equity firms, the best hedge funds tend to be closed to new money. Citadel recently returned US$7bn to its clients, as it did the previous year.

Jain Capital, a new multi-strategy fund run by former Millennium co-CIO Bob Jain, will be the largest hedge fund launch of 2024 and is targeted to be larger than the record 2017 launch of ExodusPoint by other former Millennium CIOs. Bloomberg reported that Jain Capital is offering potential large clients more heavily discounted fees than expected – an ominous sign of the current fundraising environment for the industry.

The question of limited alpha has always been a constraint to hedge funds. Large pod shops have tried to deal with this by limiting individual pod sizes but throwing bodies at the challenge, and headcount and cost growth have far outpaced new assets in recent years. As one of the UK’s most famous hedge fund managers, Paul Marshall, said recently: “Everybody wants that Cristiano Ronaldo on their team, but there aren’t very many Cristiano Ronaldos. What’s happening is everybody’s getting paid the same as Cristiano Ronaldo.”

Hedge funds of course hedge and are supposed to focus on risk-adjusted returns. But in an environment when yields on overnight rates are back, can hedge funds really survive with five-year track records of 5% per year?

We could also question to what extent the industry has been underperforming because of hedging rather than poor alpha generation.

For years the Tiger Cubs that dominated the industry hunted in packs. We would expect more diversification today. And yet Goldman said late last year that crowding – in other words, funds making pretty much the same trades – had reached its highest since it started tracking funds 22 years ago.

The hedge fund industry’s long US equity portfolio increased its exposure to the “Magnificent 7” tech stocks – Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta Platforms, Microsoft, Nvidia and Tesla – materially in 2023, in line with the trend across the stock market. This makes it exposed to any pullback in those momentum trades. Another example of crowded hedge fund positioning has been highly leveraged bets on the basis between cash and futures in US Treasuries, which is now the focus of regulators globally. There is likely to be some intervention from authorities in 2024 on hedge fund leverage.

All this suggests that 2023 may have been a peak year for investment banks' markets business from hedge funds. Shrinking client assets, leverage and headcounts of investment professionals are likely to be seen across the hedge fund industry absent a marked turnaround in returns.

If there is a silver lining for banks it may be that the talent war for the best traders consequently reduces, albeit that may take time to flow through.

Rupak Ghose is a former financials research analyst