CORRECTION - Europe eyes mutual 'defence bank’ to counter Russia threat

European nations have begun discussions around a groundbreaking financing mechanism that could raise hundreds of billions of euros in international bond markets, as the continent embarks on an unprecedented coordinated effort to upgrade its military capabilities in response to the ongoing threat from Russia – and fears that the US, which has underwritten its security since the end of World War II, has become an unreliable ally.

Finance officials from several European countries met on the fringes of the G20 meeting in Cape Town, South Africa, to discuss proposals to fund a dramatic increase in defence spending without triggering a political or market backlash for countries already facing tricky fiscal constraints. One of the options discussed was the creation of a new special purpose vehicle, a kind of European defence bank, that would fund itself in international capital markets.

Exploratory discussions have been underway for months but have gathered pace in the past few weeks. At the end of January, European leaders sent a letter to Nadia Calvino, president of the European Investment Bank, formally requesting that it begin technical work around “earmarked debt issuance for funding security and defence projects” and the impact such instruments would have on wider sovereign and supranational debt markets.

“The possibility of specific and earmarked debt issuance by the EIB for funding security and defence projects should be discussed among other options as it could enhance transparency and provide clarity as well as the possibility of choice for investors,” according to the letter, which was signed by 19 of the 27 European Union leaders.

The EIB should engage with the markets and with ratings agencies to determine “the most efficient and cost-effective” way of raising money – and to consider the impact on the EIB’s existing funding programme", the letter said.

It is almost a year since the idea of European “defence bonds” was first raised privately by France and Estonia. European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen in July added her weight to what she called a “European defence fund”, with tentative discussions beginning at the end of last year. But the events of recent weeks – including a warning from US vice-president JD Vance that Europe needs “to step up in a big way to provide for its own defence” – has increased the urgency.

The UK has separately floated the idea of a “re-armament bank”, modelled on the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, which would also finance itself in the markets.

Existing mechanisms

An EU-wide defence bank is likely to replicate the European Financial Stability Facility and the European Stability Mechanism, which were born out of the eurozone debt crisis, and leveraged capital and guarantees from states to raise hundreds of billions in the markets. A similar structure was used for the NextGenerationEU fund, which leveraged a guarantee from the European Union budget to launch an €800bn bond market programme – one of the world’s biggest – in an effort to stimulate the bloc's recovery from Covid-19.

“There is a precedent for eurozone countries creating new entities at a critical time,” said Arnaud Louis, an analyst at Fitch.

But while various options exist right out of the box, political divisions within the EU will make repurposing or replicating any existing vehicles almost impossible (even though the ESM has more than €420bn of unused capacity). Doing so would require unanimity, an unlikely outcome given Hungarian opposition and reservations among some northern member states about guaranteeing the debts of the southern and eastern flank. Others like Austria, Cyprus, Ireland and Malta are also bound by military neutrality, another hurdle to unanimity.

“A centralised pillar of funding would be hugely controversial from a political perspective,” said Armin Steinbach, professor of EU law and economics at HEC Paris and a fellow at the Bruegel thinktank. “We would need 27 members unanimously confirming that we are doing a debt-financed construct for defence. And then you have the legally more problematic issue: that the EU budget cannot legally be used to pay for military expenditure. To get around that, you would again need 27 member states approving in the council, and then you would need national ratification in 27 member states.”

Asking the EIB to assess how a scheme might work bypasses that problem for now – not least because decision-making at the bank doesn't require unanimity between the 27 EU members that make up its shareholder base. Shareholdings are weighted by economic clout, and a simple majority is enough, effectively meaning that Germany, France and Italy can drive through any decisions by themselves. But any final scheme is unlikely to be part of the EIB architecture – not least because it is an EU institution, and any continent-wide scheme would likely include non-member states such as the UK and Norway.

Capital is key

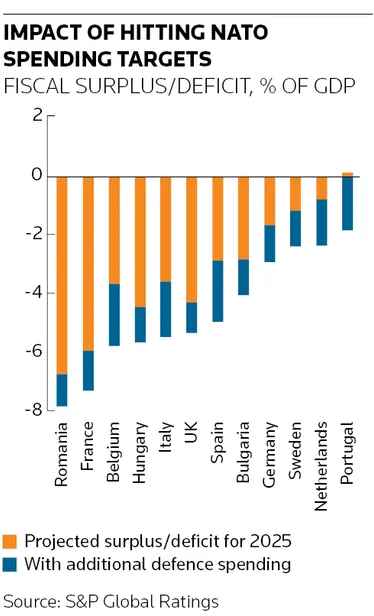

Any scheme is likely to be enormous – possibly even dwarfing the €800bn NGEU programme, which turned the EU into one of the world’s largest bond issuers. Analysts predict that Europe will need to raise defence spending to a minimum of 3% of gross domestic product – and possibly more. The Bruegel thinktank estimates that would require more than €250bn of additional spending every year. While some of that increase would happen at a national level, the fund would likely need to have a budget of at least €500bn to be effective.

With the EU set to issue €160bn of bonds this year, and the EIB planning €60bn, any technical assessment is likely to focus on the impact any new issuance might have on yields. But bankers are confident the market can absorb additional supply.

“What we’ve seen with the public sector bond market in general is that it is extremely adaptable,” said a sovereign bond banker. “There is a price for almost every additional volume of funding. We’ve seen that with Covid-19 very nicely, when volumes almost doubled and still the market worked and digested it.”

Coordinating funding, while politically difficult to agree, could bring savings. At present, only Denmark, Sweden and Germany are able to raise money in the markets more cheaply than the EU. Many countries could save vast sums by raising money collectively – Romanian 10-year bonds trade 500bp wider than their EU counterparts and Poland's are 400bp wider. Coordination might also help in terms of equipment procurement.

Free-riders

Like the EFSF and ESM before it, any new fund will likely be built on the assumption that countries will stand behind any bond issuance – either by injecting capital or through guarantees. Fiscally conservative countries may find that politically difficult, as they did during the eurozone crisis. But this time it would be even more complicated given the voluntary nature of the scheme and the potential inclusion of non-EU member states, raising the prospect of some countries leaving the mechanism.

Some may also complain that the voluntary nature would allow some countries to free-ride on continent-wide defence initiatives.

“International agreements tend to be much less rigid – practically – than European treaties,” said Steinbach. “A worst-case scenario would be that you would have a political turnaround, and a country would say: ‘we are no longer interested in this'. Obviously, you would design any agreement so that any country would be obliged to repay and pay for what the previous government has committed – but, still, the market reaction could be quite adverse.”