Still in good order: traders shrug off rising Gilt yields

Trading conditions in UK government bond markets have remained orderly in recent weeks, bankers say, despite the country's long-term borrowing costs rising to levels last seen in the late 1990s.

The yield on 30-year UK debt hit a peak of 5.7% on September 2, the highest level since 1998, amid mounting concerns over the health of the UK's finances ahead of the government's November budget.

Yields have since retraced to about 5.4% following a rally in global bond markets, but remain roughly 30bp above the peak registered during the Gilt market crisis in September 2022 that was triggered by former prime minister Liz Truss’s disastrous mini-budget.

Traders are quick to reject comparisons to that tumultuous period despite Gilt yields now resting at higher levels. The underlying health of the market remains intact, they say, as a months-long rise in yields has given investors time to adjust – a stark contrast to the 200bp yield surge in the space of four days in 2022.

“It's not necessarily the outright level of yields that's really the issue but the speed at which they sell off, and in 2022 we saw huge volatility in a very short period of time," said Carina Lindberg, head of GBP trading at Nomura. "Recent Gilt moves haven't been disorderly [and] we haven’t seen any signs of distress selling, unlike in 2022. So, it’s a completely different situation to what happened in 2022.”

Global rise

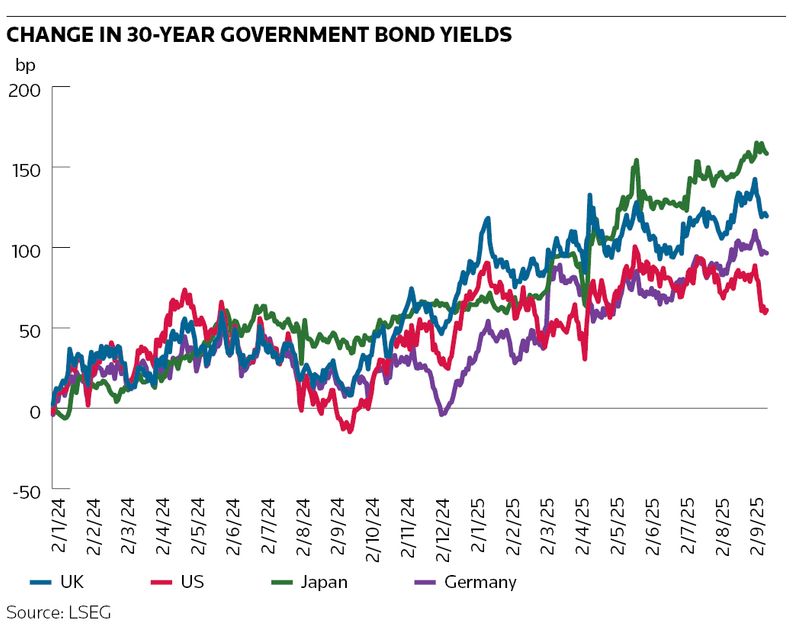

Long-dated bond yields have been climbing across the globe for much of this year as countries from the US to Japan have been forced to issue more debt to plug holes in their finances. That has coincided with waning demand from what were some of the most stalwart buyers of long-dated government debt: pension funds and insurance companies.

The yield on 30-year Japanese debt has risen even faster this year than equivalent UK yields to an unprecedented 3.3% amid mounting concerns over Tokyo's record ¥115trn (US$778bn) budget and local institutions reducing their purchases.

Long-dated US and German yields have also climbed as governments on either side of the Atlantic have loosened their purse strings and triggered a sharp rise in debt issuance, underscoring how the UK isn't alone in facing spiralling borrowing costs.

"We’re seeing a global theme of excessive bond issuance versus reduced investor demand," said Francis Diamond, head of European rates strategy at JP Morgan. "Multiple countries are running large deficits yet there’s no obvious demand for that debt, so price-conscious investors are requiring an additional term premium to compensate them for the uncertainty that a lack of fiscal tightening brings when holding debt.”

Despite this challenging backdrop, there have been encouraging signs that investors are far from souring on UK debt and that higher yields may even be attracting more buyers. The UK government sold a record £14bn of new 10-year Gilts on September 2, the day 10-year yields hit their highest level since 2008, with a record £141bn of demand.

Traders also point to signs of healthy secondary market trading conditions. Guy Winkworth, UK head of rates trading at Barclays, said the relative value between different UK bonds is better now than at the start of the year and there are no signs of stress in the repo market.

“The broader health of the Gilt market is quite good,” he said. “Market function is good and there are no weird dislocations or liquidity issues within the main instruments."

No crisis here

That is all a far cry from the Gilt market crisis in 2022 when the Conservative government's mini-budget announcement sent long-dated yields spiralling higher, triggering a self-reinforcing firesale among pension funds that employed liability-driven investment strategies.

Investors using those strategies, which ran leveraged Gilt positions, found themselves in a doom loop of selling Gilts to meet margin calls – a move that pushed yields higher and triggered fresh margin calls. Ultimately, the Bank of England was forced to intervene to calm the market. LDI funds have since overhauled their operations to bolster their defences against such scenarios.

Now, part of the reason 30-year yields have risen to multi-decade highs is because of a drop-off in demand for bonds from pension funds after years of heavy buying. That has already prompted the UK to lower the amount of long-dated debt it sells.

Just 10% of the £300bn in bonds that the UK Debt Management Office is scheduled to issue by the end of the year will come in the form of 30-year debt. In 2021, long-dated Gilts made up roughly one-third of the DMO’s issuance.

“If 30-year Gilt yields being this high is a concern, the DMO can further reduce its issuance of new long-dated debt, so rising yields are a bit of a non-issue,” said Sam Cartwright, UK economist at Societe Generale.

In the meantime, all eyes will be on November's budget – and whether chancellor Rachel Reeves' fiscal plans will require more borrowing than investors expect.

“The budget is definitely the most important catalyst for Gilt yields going forward as it will forecast how much money the government is going to have to borrow and therefore how many Gilts the investors and banks are going to have to digest,” said Winkworth.