Sales of synthetic collateralised debt obligations have increased sharply in 2022, marking a dramatic turnaround in fortunes for this complex corner of credit markets after the global pandemic brought issuance to a standstill.

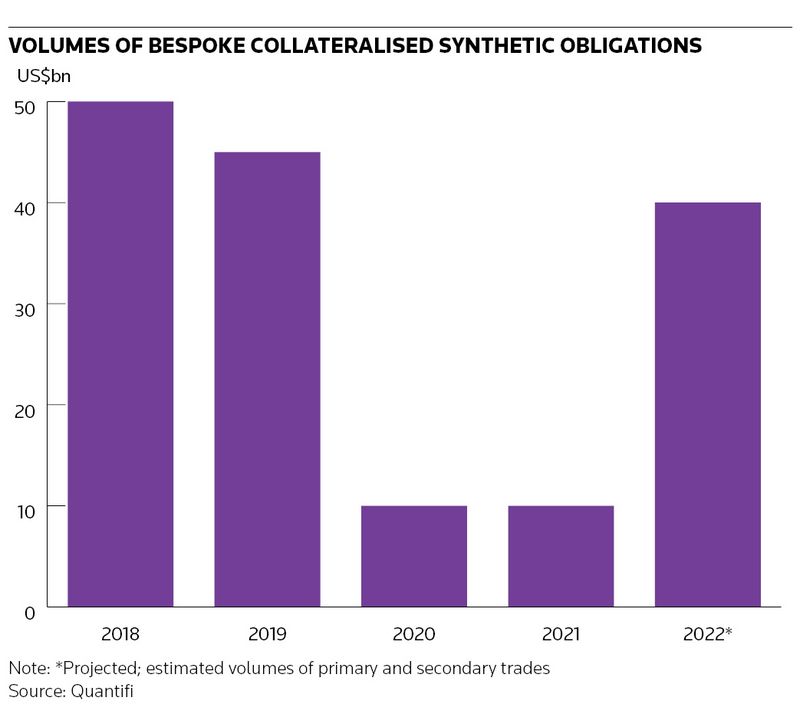

Volumes of bespoke collateralised synthetic obligations – a type of synthetic CDO that carves up pools of credit default swaps linked to corporate debt – are on track to quadruple this year to about US$40bn, according to projections from risk and analytics firm Quantifi.

The rebound suggests investor appetite for these highly engineered and leveraged products hasn’t diminished despite severe bouts of market volatility over the past two years that inflicted eye-watering losses on one of the largest and most high-profile investors in this space.

While activity has slowed since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, bankers say investors are poised to take advantage of credit spreads widening to their most distressed levels since late 2020, once markets settle down.

“CSOs are back,” said Sukho Lee, a senior structured credit trader at Nomura, who pointed to a decent pipeline of deals after a “bit of a flurry” in January and February. “Underlying credit spreads are wider and credit curves are flatter. It’s a good time for credit pickers to go long and get full control over credit selection.”

The synthetic CDO machine was once synonymous with the kind of excessive financial engineering that led to the great crisis of 2008. As well as fuelling extraordinary growth in credit derivatives, these products acted as a vehicle to spread and amplify losses in sub-prime mortgages around the globe.

Sub-prime CDOs have been consigned to the dustbin of history. But a handful of banks (notably BNP Paribas, Citigroup, JP Morgan and Nomura) have succeeded in rehabilitating the corporate CDS-linked part of the synthetic CDO market over the past several years. Their ranks have grown to include Goldman Sachs, which re-entered the bespoke CSO market this year with a couple of deals, according to sources familiar with the matter.

“The credit crisis was mostly about sub-prime mortgages, but it ended up really hurting these credit structures too,” said Dmitry Pugachevsky, director of research at Quantifi. “All the bespoke activity stopped – people didn’t want to touch them at all. Now these products have proven for several years that they are stable and provide good returns for sophisticated investors that are looking for this kind of leveraged exposure to credit.”

Big risks, big rewards

CSOs’ return to favour coincided with a steep rise in the amount of negative-yielding debt sloshing around markets a few years ago. Their appeal was simple: the promise of heady returns. Those are achieved – at least in theory – by allowing investors to make leveraged bets on how likely certain companies are to default on their debt in the coming years. The bank arranging the trade does that by slicing a pool of CDS into tranches with varying degrees of risk and return.

In this way the structures resemble the more mainstream collateralised loan obligation market, where bank loans are bundled together. And while synthetic CDOs may have a chequered history, veterans of these markets argue they are no more complicated than CLOs.

“They’re actually simpler than a CLO,” said one structured credit expert, who invests in both markets, noting that certain features of the CSO such as its fixed maturity and static pool of credits make it easier to value using financial models. “It’s much easier to get your hands around what risk am I taking."

In a “bespoke” CSO, the equity investor (who buys the riskiest slice) gets to choose which companies’ CDS are in the portfolio. They're also on the hook for any losses arising from the first few defaults, usually up to 5% or 10% of the portfolio. In return, they can earn as much as 30% to 40% a year depending on the amount of leverage they deploy.

Investors in the more senior debt slices earn lower returns, but have a greater level of protection from defaults. Deals are typically US$500m to US$1bn in size, containing 80 to 100 names spread across US and European credit markets, and tend to be one to two years in maturity.

“These trades are short-dated because clients are good at picking credit over one-to-two-year horizons," said Davy Kim, co-head of synthetic structured credit trading at Citigroup. "It's important to use liquid CDS in these baskets so both us and clients can hedge out the underlyings if needs be. That’s one of the advantages of this product."

Still, there's no disguising the fact that this is a risky business and defaults do happen – particularly when a global pandemic arrives out of nowhere. Hedge fund CQS, one of the most prominent CSO investors of recent years, sustained heavy losses in 2020 and has not since been involved in new deals. A spokesman for CQS declined to comment.

Perhaps surprisingly, traders say the broader market held up well despite this high-profile blow-up even as volatility soared and new issuance halted.

“The client losses in 2020 ended up being an isolated case that didn’t really affect the rest of the business,” said Paul-Louis Laferrere, a senior credit structurer at BNP Paribas. “We saw new equity investors coming in – specialised credit funds and people who usually look at CLO equity tranches. Those newcomers may help explain the resilience of the markets.”

Newcomers

Such new arrivals will encourage banks, which have looked to cultivate a wider range of institutional investors to help foster the growth of this market. Many say the ability of banks to broker billions of dollars worth of secondary market trades in 2020 as funds looked to reshuffle exposures may partly explain the broadening appeal of CSOs.

The fact that banks could trade these products at all during those turbulent markets shows how radically they've overhauled their businesses since the 2008 crisis. Banks now must sell the entire CSO stack or else hold punitively high amounts of capital against anything they retain. That reduces their exposure to market moves, giving them greater leeway to help clients with their own risk management during times of stress.

Banks have even managed to bring in new investors that don't ordinarily trade derivatives by offering them “fully funded” CSOs. This is where the bank sells the investor a note tracking the performance of the chosen CDS pool. That lowers the amount of leverage involved compared to using a swap to gain exposure (where only a portion of the investment amount must be posted upfront as margin), but the equity investor can still make around 15% to 20% a year in returns.

Credit picking

Buying a CSO is not for the faint-hearted in these volatile markets. Credit spreads on US high-yield bonds have jumped to just under 500bp, according to ICE BofA indices, their most stressed level since November 2020. But funds with the know-how are warming to the idea of CSOs again, bankers and investors say, with one new deal printing earlier this month and more expected to follow.

The trick for the equity investor is to select a mixture of higher-yielding investment-grade credits and lower-rated names that are unlikely to default before the transaction matures. Getting it right is all the more important considering deals are static and CDS in the portfolio can't be switched, despite some failed attempts to introduce managed CSOs in early 2020.

"We are actively discussing deals with a few clients at the moment," said BNPP's Laferrere. "Levels are more attractive now, but the question for equity investors is: are they willing to take so much risk?”

Corrects spelling of Pugachevsky in eighth paragraph